The Nanovic Institute for European Studies at the University of Notre Dame announces the 2024 shortlist for the Laura Shannon Prize in Contemporary European Studies. Carrying an award of $10,000, the Laura Shannon Prize is recognized internationally as one of the leading book prizes in the field of European studies. Each year, the Nanovic Institute, which is part of the Keough School of Global Affairs, gives this award to the author of the best book in European studies that transcends a focus on any one country, state, or people to stimulate new ways of thinking about contemporary Europe as a whole.

The 2024 prize will be awarded to the best book in the humanities published in 2021 or 2022. The winning book, which will be announced in January 2024, will be selected by a jury of five eminent scholars in European studies, at least three of whom are faculty at institutions other than the University of Notre Dame.

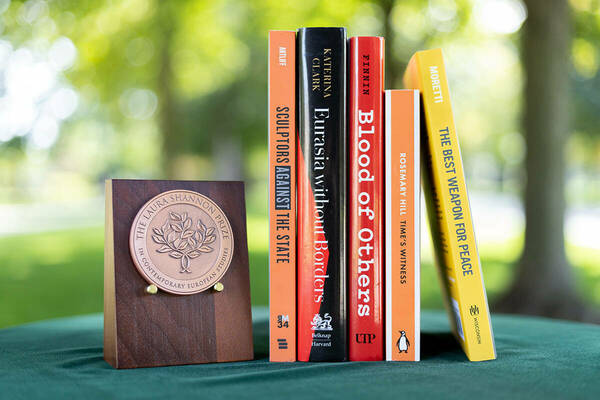

The finalists for the 2024 Laura Shannon Prize are:

- “Sculptors Against the State: Anarchism and the Anglo-European Avant-Garde” by Mark Antliff (Penn State University Press, 2021);

- “Eurasia Without Borders: The Dream of a Leftist Commons, 1919-1943” by Katerina Clark (Harvard University Press/Belknap Press, 2021);

- “Blood of Others: Stalin’s Crimean Atrocity and the Poetics of Solidarity” by Rory Finnin (University of Toronto Press, 2022);

- “Time’s Witness: History in the Age of Romanticism” by Rosemary Hill (Allen Lane of Penguin Press, 2021);

- “The Best Weapon for Peace: Maria Montessori, Education, and Children’s Rights” by Erica Moretti (University of Wisconsin Press, 2021).

Stella Ghervas, author of “Conquering Peace: From the Enlightenment to the European Union” (Harvard University Press, 2021) and Laura Shannon Prize winner in history and the social sciences, will accept the 2023 prize with a lecture on November 2, 2023. The 2024 winner of the Laura Shannon Prize will also accept their prize with a lecture next year.

Nominations for the 2025 history and the social sciences cycle (for books published in 2022 or 2023) are currently being accepted and are due by March 1, 2024. For more information on the nomination process, please visit the Nanovic website.

First awarded in 2010, the Laura Shannon Prize is made possible through a generous endowment from Mrs. Laura Shannon (1939-2021) and her husband, Michael ’58. Mrs. Shannon served as a member of the Nanovic Institute’s Advisory Board for many years after joining in 2003. As well as her work in social services and family court mediation, she was a regular visitor to Europe, particularly to France, where she honed her language skills and explored libraries and cultural centers. Mr. Shannon is president of MEShannon & Associates, a Houston-based financial consulting firm. The Shannons have two daughters, Claire and Kathryn, who, as members of the institute’s advisory board, are continuing their parents’ legacy of commitment to and engagement with the Nanovic Institute.

Titles and summaries of the Laura Shannon Prize 2024 shortlist

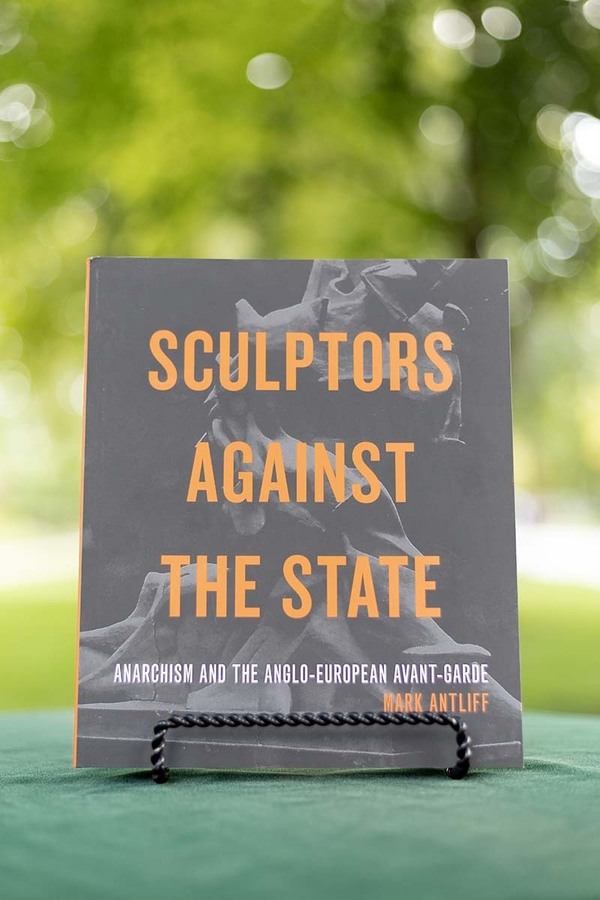

“Sculptors Against the State: Anarchism and the Anglo-European Avant-Garde” by Mark Antliff (Penn State University Press, 2021)

“Sculptors Against the State” considers the relation of anarchist ideology to avant-garde sculpture through an examination of three iconic artists whose work transformed European modernism: Umberto Boccioni, Jacob Epstein, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Addressing such complex subjects as sexual liberation, homosexuality, the history of emotions, the ethics of violence, and tactics of nonviolent resistance, Mark Antliff demonstrates how sculptural processes were shaped by forms of anarchism calculated to foster a radical community.

The anarchist view that the State is a state of mind and a set of social relationships is a central theme Antliff uses to explore not only the art of Boccioni, Epstein, and Gaudier-Brzeska but also the associated aesthetics of radical luminaries such as Oscar Wilde, F. T. Marinetti, and Ezra Pound. Taking Boccioni’s “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space,” Epstein’s “Tomb of Oscar Wilde,” and Gaudier-Brzeska’s “Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound” as a starting point, Antliff argues that these sculptors saw the arts as a radical catalyst for an entirely new constellation of interpersonal relations and psychological dispositions—ones antithetical to those propagated by the State.

Powerfully argued and informed by extensive archival research, “Sculptors Against the State” provides a new understanding of these artists, even as it sheds light on why contemporary anarchist theory is necessary for understanding the profound cultural impact modernism had during the twentieth century. Antliff’s work will be of interest to students and scholars of modernist art and literature, particularly those who study the intersections between artistic practice and politics.

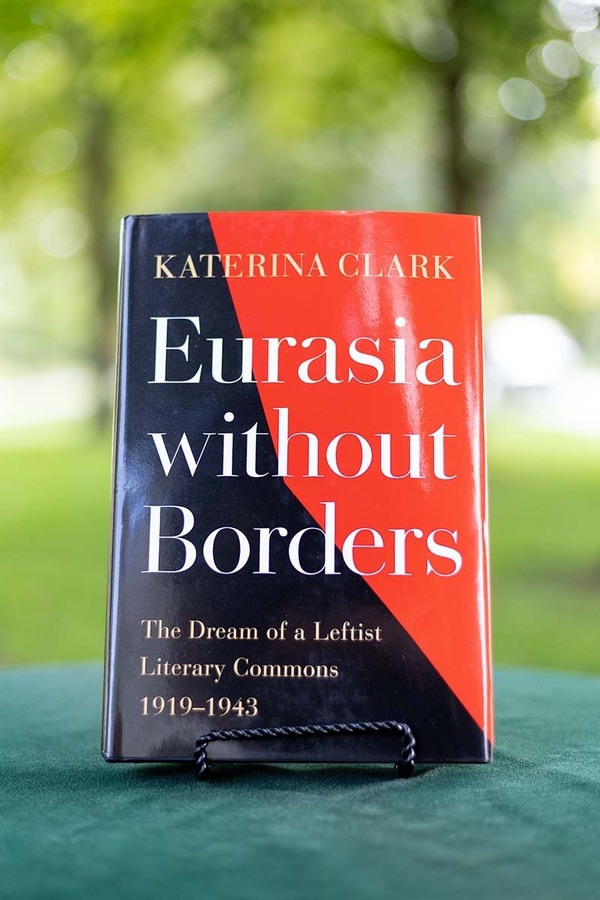

“Eurasia Without Borders: The Dream of a Leftist Commons, 1919-1943” by Katerina Clark (Harvard University Press/Belknap Press, 2021)

Katerina Clark charts interwar efforts by Soviet, European, and Asian leftist writers to create a Eurasian commons: a single cultural space that would overcome national, cultural, and linguistic differences in the name of an anticapitalist, anti-imperialist, and later antifascist aesthetic. At the heart of this story stands the literary arm of the Communist International, or Comintern, anchored in Moscow but reaching Baku, Beijing, London, and parts in between. Its mission attracted diverse networks of writers who hailed from Turkey, Iran, India, and China, as well as the Soviet Union and Europe. Between 1919 and 1943, they sought to establish a new world literature to rival the capitalist republic of Western letters.

“Eurasia without Borders” revises standard accounts of global twentieth-century literary movements. The Eurocentric discourse of world literature focuses on transatlantic interactions, largely omitting the international left and its Asian members. Meanwhile, postcolonial studies have overlooked the socialist-aligned world in favor of the clash between Western European imperialism and subaltern resistance. Clark provides the missing pieces, illuminating a distinctive literature that sought to fuse European and vernacular Asian traditions in the name of a post-imperialist culture.

Socialist literary internationalism was not without serious problems, and at times it succumbed to an orientalist aesthetic that rivaled any coming from Europe. Its history is marked by both promise and tragedy. With clear-eyed honesty, Clark traces the limits, compromises, and achievements of an ambitious cultural collaboration whose resonances in later movements can no longer be ignored.

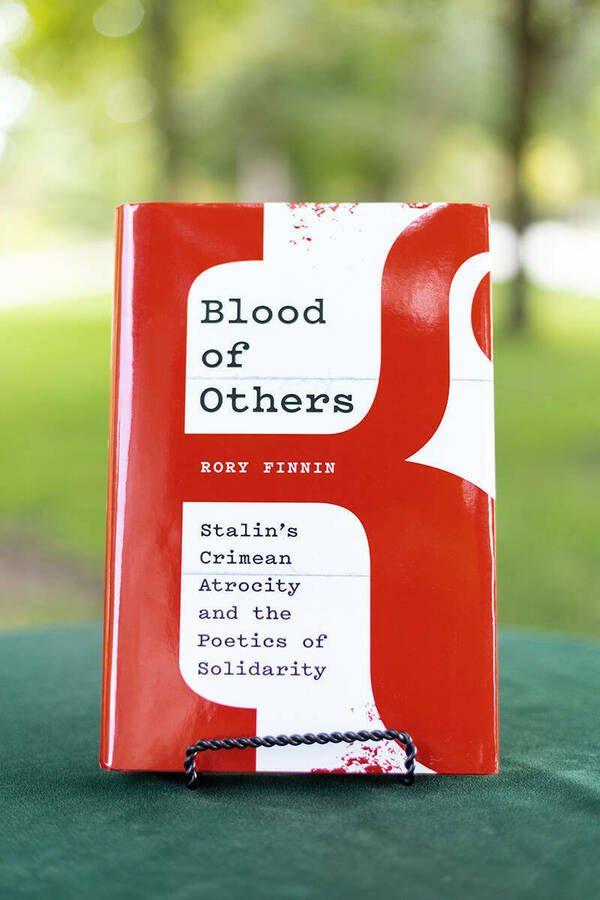

“Blood of Others: Stalin’s Crimean Atrocity and the Poetics of Solidarity” by Rory Finnin (University of Toronto Press, 2022)

In the spring of 1944, Stalin deported the Crimean Tatars, a small Sunni Muslim nation, from their ancestral homeland on the Black Sea peninsula. The gravity of this event, which ultimately claimed the lives of tens of thousands of victims, was shrouded in secrecy after the Second World War. What broke the silence in Soviet Russia, Soviet Ukraine, and the Republic of Turkey were works of literature. These texts of poetry and prose—some passed hand-to-hand underground, others published to controversy—shocked the conscience of readers and sought to move them to action.

“Blood of Others” presents these works as vivid evidence of literature’s power to lift our moral horizons. In bringing these remarkable texts to light and contextualizing them among Russian, Turkish, and Ukrainian representations of Crimea from 1783, Rory Finnin provides an innovative cultural history of the Black Sea region. He reveals how a "poetics of solidarity" promoted empathy and support for an oppressed people through complex provocations of guilt rather than shame.

Forging new roads between Slavic studies and Middle Eastern studies, “Blood of Others” is a compelling and timely exploration of the ideas and identities coursing between Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine—three countries determining the fate of a volatile and geopolitically pivotal part of our world.

“Time’s Witness: History in the Age of Romanticism” by Rosemary Hill (Allen Lane of Penguin Press, 2021)

Between the fall of the Bastille in 1789 and the opening of the Great Exhibition in 1851, history changed.

The grand narratives of the Enlightenment, concerned with kings and statesmen, gave way to a new interest in the lives of ordinary people. Oral history, costume history, the history of food and furniture, Gothic architecture, theatre, and much else were explored as never before. Antiquarianism, the study of the material remains of the past, was not new, but now hundreds of men - and some women - became antiquaries and set about rediscovering their national history, in Britain, France, and Germany.

The Romantic Age valued facts, but it also valued imagination and it brought both to the study of history. Among its achievements were the preservation of the Bayeux Tapestry, the analysis and dating of Gothic architecture, and the first publication of “Beowulf.”

It dispelled old myths and gave us new ones: Shakespeare's birthplace, clan tartans, and the arrow in Harold's eye are among their legacies. From scholars to imposters the dozen or so antiquaries at the heart of this book show us history in the making.

“The Best Weapon for Peace: Maria Montessori, Education, and Children’s Rights” by Erica Moretti (University of Wisconsin Press, 2021)

The Italian educator and physician Maria Montessori (1870–1952) is best known for the teaching method that bears her name. She was also a lifelong pacifist, although historians tend to consider her writings on this topic as secondary to her pedagogy. In “The Best Weapon for Peace,” Erica Moretti reframes Montessori's pacifism as the foundation for her educational activism, emphasizing her vision of the classroom as a gateway to reshaping society. Montessori education offers a child-centered learning environment that cultivates students' development as peaceful, curious, and resilient adults opposed to war and invested in societal reform.

Using newly discovered primary sources, Moretti examines Montessori's lifelong pacifist work, including her ultimately unsuccessful push for the creation of the White Cross, a humanitarian organization for war-affected children. Moretti shows that Montessori's educational theories and practices would come to define children's rights once adopted by influential international organizations, including the United Nations. She uncovers the significance of Montessori's evolving philosophy of peace and early childhood education within broader conversations about internationalism and humanitarianism.