The power of words and the power of truth were the foci of an April 19 panel discussion on the poem “мама” (“Mother”) from the chapbook Деякі вірші (Some Poems) by the Ukrainian poet Halyna Kruk. This event, co-sponsored by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies and the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies at the Keough School of Global Affairs, brought together panelists whose personal and scholarly interpretations of this work of written art — originally in Ukrainian and then translated into English and Irish — offered an opportunity to reflect on the human stories of the war in Ukraine.

Nanovic Institute Director Clemens Sedmak, professor of social ethics in the Keough School, introduced the panel and explained that it was part of the institute’s broader commitment to keeping attention on the war in Ukraine. Ensuring the visibility of Ukrainian people on campus, including visiting scholars and students from Ukrainian Catholic University, is perhaps the most important element of this work. The discussion of “мама,” Sedmak explained, recognized “the special power that only voices from Ukraine can bring, a special power in words.” In the context of this war, Sedmak explained, Halyna Kruk’s trilingual poem provided the ideal impetus for a discussion of “the power of different languages and the power of poetry to be both disruptive and a bridge builder.”

Forming connections through poetry

The panel came together through a chain of coincidental linkages to Kruk and her poetry. By chance, Siobhán O’Grady, Cairo bureau chief and foreign correspondent for The Washington Post, heard Kruk speak in person during an event at the Kyiv office of PEN, an international writers’ organization, the Ukrainian branch of which Kruk is vice president. O’Grady was deeply moved by the energy in the poet’s voice and the defiance of the audience who listened intently to Kruk’s words, unmoved by the sound of air raid sirens in the background. Taking the opportunity to speak to Kruk, O’Grady discovered that “мама” had been translated into English and Irish. The poem had then been read in three languages, at an event in Cork, Ireland. When read in Irish, it moved many in the audience to tears.

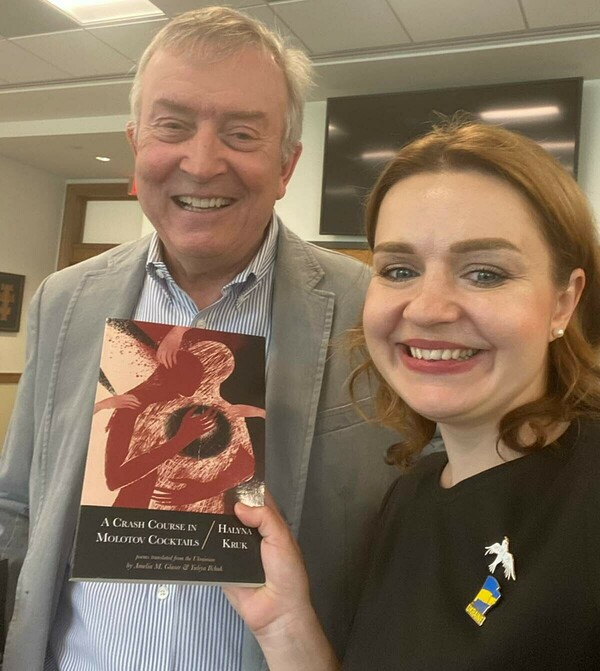

Kruk gave O’Grady, who is of Irish heritage, a copy of her trilingual chapbook Some Poems (Деякі вірші), and inscribed it, in Irish, to her father Thomas O’Grady, poet, literature professor, and scholar-in-residence at Saint Mary’s College. Professor O’Grady realized that one of Kruk’s editors is a close friend. He shared the chapbook with his colleague at Notre Dame, Brian Ó Conchubhair, associate professor of Irish language and literature and Nanovic Institute faculty fellow, who discovered that he knows one of the Irish translators. Thus, the idea for a panel discussion at Notre Dame emerged.

“Every individual we encounter in life leaves an impression on us, and their presence in our lives is not a matter of chance. Even if we get to know this person through poetry.”

- Halyna Protsyk

Halyna Protsyk, director of international academic relations at Ukrainian Catholic University, took the fourth seat on the panel, and, although she had never met Kruk, discovered her life shares many parallels with the poet. In addition to sharing a first name, both women hail from Lviv, and Kruk now teaches at Ivan Franko National University in Kyiv, where Protsyk earned her undergraduate and graduate degrees. Now a visiting scholar at the Nanovic Institute, Protsyk was invited to join the panel and had a reflective conversation with Kruk in advance. Describing this conversation, Protsyk shared that “every individual we encounter in life leaves an impression on us, and their presence in our lives is not a matter of chance. Even if we get to know this person through poetry.”

Human stories in a ubiquitous war

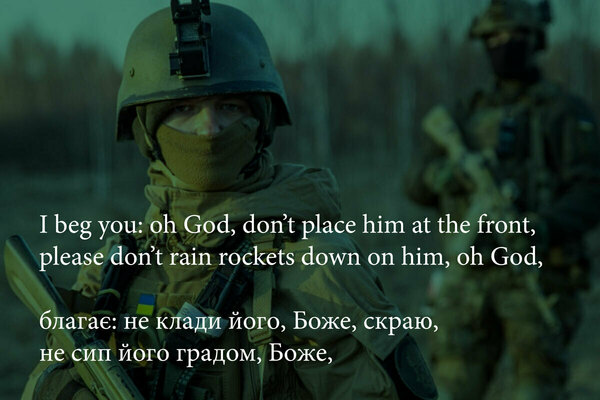

Siobhán O’Grady shared the experiences and memories that stood out to her from her time in Ukraine for the Washington Post. O’Grady found herself particularly moved by human stories and, especially, family stories. These encounters are part of the reason she was so drawn to the poem “мама.” Kruk’s poem evokes the reflections and despair of a mother whose son is at war as she pleads with Death to recognize her child’s innocence. She prays:

“I beg you; oh God, don’t place him at the front,

please don’t rain rockets down on him, oh God,”

O’Grady recalled one such family story — that of 31-year-old Maksym Omelianenko and his mother Lyudmila — that she reported on following a deadly Russian cruise missile attack on a nine-floor apartment building in Dnipro in January 2023. Prior to this attack, which left dozens dead and more injured, Maksym had been fighting at the front in Bakhmut. The soldier had assumed that his mother, at home in her apartment in Dnipro and far from the worst of the fighting, was relatively safe. O’Grady was among those standing in the snow as Lyudmila, who made herself visible by waving a piece of cloth from the top floor of the devastated building, was rescued and brought to the hospital to be treated for crushed legs and other injuries. Maksym was able to visit his mother briefly before departing again for the frontline. “Of course, she’s very worried for me,” he told O’Grady, “but she understands that we’re doing it for all of Ukraine.”

“Of course, she’s very worried for me, but she understands that we’re doing it for all of Ukraine.”

- Maksym Omelianenko

O’Grady also reflected upon her observation that Ukrainian civilians have been “exposed to the sounds of war so intently that they know the difference [between outgoing or incoming rockets].” This wartime acumen is something she witnessed even among small children. During a visit to Bucha, where Russian soldiers brutally massacred more than 400 civilians in March 2022, she visited a school where young children take their classes in a school gym patrolled by soldiers in sniper gear. The teachers wept as they described how the children had changed. Those as young as nine already understood the vocabulary of war, using, for example, military terminology for the launching and landing of rockets.

In their analysis of “мама,” Professors Ó Conchubhair and O’Grady also reflected on the way in which poetry gives expression to the human face of war. Quoting W.H. Auden, O’Grady asked, “Here is a verbal contraption, how does it work?” He showed how the central voice — the mother — switched from talking to her son (“someone stands between you and death”) to addressing Death, now capitalized and personified, directly (“my heart whispers: Death, he hasn’t ripened yet”). Reflecting on the ways in which the poem “entered me and left me,” O’Grady said that his devastating conclusion was that the mother was “left at a complete loss of words to describe what she’s experiencing.”

Ó Conchubhair’s analysis considered the voice and perspective emphasized in “мама,” and he suggested that the poem resonated with an Irish audience because it conveys a human experience that is universal. It could be read, he said, as “a poem of rawness, emotion, out of time and out of place.” Ó Conchubhair also commented on the production of this trilingual chapbook, which, as an inexact translation and imperfect printing, conveys the roughness and rawness of people confronting war.

“A poetry of emotional fact, a poetry of immediate reaction”

In her reflections on “мама,” Protsyk drew the audience’s attention to the human stories in a war that has become ubiquitous in Ukrainian daily life. She noted that the poem was written after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 but before the full-scale invasion of February 2022. Given how the Russian invasion has expanded, Protsyk and Kruk agree that the last two lines no longer represent Ukrainians’ experience of war:

“I don’t even know what a rocket looks like,

my son, I can’t picture the war even to myself.”

“War is now ubiquitous,” Protsyk explained. “It is behind every shoulder, affecting every family, and concerns everyone.” Sharing her conversation with Kruk, Protsyk traced a development in Ukrainian poetry and other writing over the last decade. While poets writing between 2014-2021 could afford to be reflective, the work produced after the full-scale invasion is more direct, dispensing with artistic play, allusions, and metaphors. Kruk describes the new form as “a poetry of emotional fact, a poetry of immediate reaction.” In this context, Protsyk explained, words have greater weight, can help people verbalize and confront the trauma of war, and provide a way for those whose lives are threatened to “bear witness to their existence.” Ukrainian war poems, Protsyk said, are testimonies that allow individuals to retain and preserve their humanity, “a deep process that brings us back to the meaning of the written word.”

As Protsyk reflected, the Ukrainian mother evoked in “мама,” whose knowledge of war is indirect, has been replaced by new images of the Ukrainian mother in war. These include “a refugee mother having fled home with her 2.5 million children in tow … an orphan mother who had her 16,000 children kidnapped and transported illegally to Russia with no further information about their destiny,” mothers who have been murdered and raped, mothers now responsible for healing their children’s psychological scars, supporting their veteran children, or fighting on the front lines themselves. Or, a mother like Lyudmila in Dnipro, who knows exactly what the rockets that rain down on her son Maksym look like and who prays for the day when she can tell him, to quote Protsyk: “Shhh, it’s all over. We survived … We remained human. We remained Ukrainians.”