Writing the War in Ukraine

By Sofiia Dobko

I remember the night of February 24, 2022, when I saw CNN news broadcasting the start of Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine. I remember the reports about massive missile strikes all over Ukraine trying to knock down anti-missile defense systems. I remember the 40-mile-long column of Russian tanks heading to Kyiv, threatening untold loss of life and making the chances for survival of the Ukrainian people close to nothing. I remember my shock and the sense that I was incapable of processing the immense emotions that seized my psyche. The experience of war is overwhelming. It is bigger than what one could ordinarily handle and extremely difficult to describe with words that truthfully reflect its horrible reality. Such difficulty comes not only from war’s perverse character, which defies human imagination but also from the acute awareness that such things require an immediate lived experience. War cannot be fully experienced from a distance.

Did you ever have to explain a joke to a person who did not know the specific cultural, political, or linguistic reference used in its context? Afterward, you probably felt uneasy because you wanted to share something very witty with someone you assumed would get it. The unwritten rule of humor is that by explaining a joke, you not only take away its charm, but you kill it entirely. Either you understand or you do not; “If you get it, you get it.”

This analogy is far from perfect. The war is not a joke. The war is a human tragedy. But similarly to a joke, war requires a personal reference point and experience to be understood and articulated.

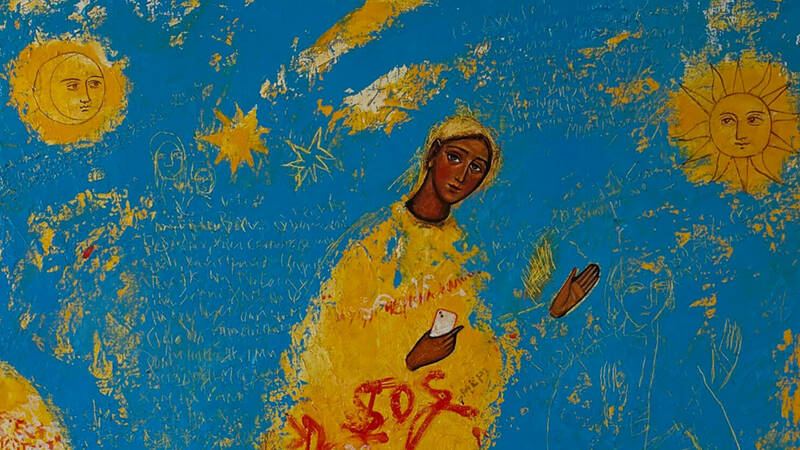

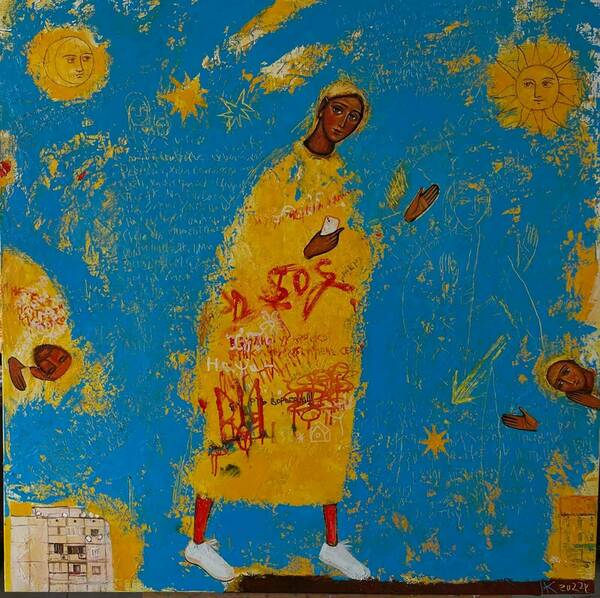

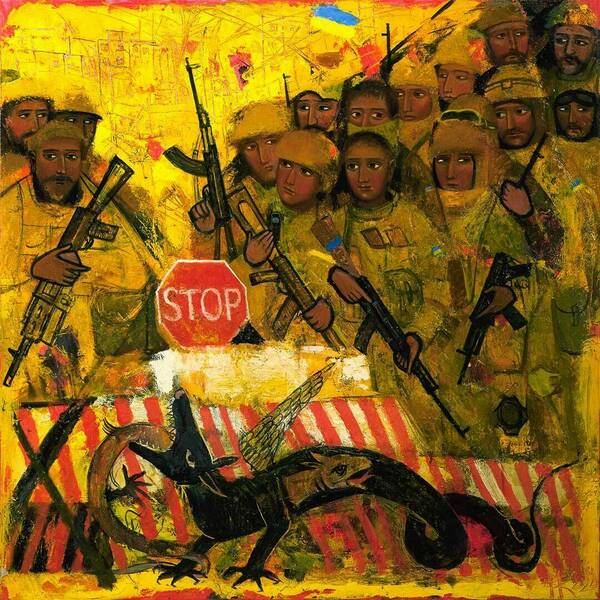

"Words" by Kateryna Kosianenko. Used with permission.

Last year, I often found myself in situations where I was at a loss for the appropriate words to bring my point home to my listeners. I was taking part in an exchange program that brought students from my home institution, Ukrainian Catholic University, to the University of Notre Dame, and I saw my role as a Ukrainian ambassador on campus, voicing the tragic story of my people, but I still struggled to find the words, sentences, and overall language to convey how both I and my home have been experiencing this invasion. What could I say? How could the pain of every Ukrainian be described to people who grew up in a foreign country, speak a different language, follow variant cultural traditions, and simply would not have a frame of reference that would allow them to connect with what was happening in Ukraine?

My own lack of firsthand experience has only complicated the situation. At the time of this writing in August 2023, I have not been home for one year, seven months, and ten days. I have not witnessed an active war with my own eyes. I have not been woken in the middle of the night by the sound of sirens and air raids. I have not been forced to hide in a bomb shelter for even a few hours, never mind a few days. I was not forced to flee my home because all that remained was ruins. For me, the guilt of physical safety has kept pace with the struggle to find the appropriate words for my testimony. How do I testify to something I have not lived through, to something that has been happening more than five thousand miles away, but that has still felt so painfully close, permeating my reality every day? During this time, I have often thought of the phrase “a quarrel in a faraway country, between people of whom we know nothing,” which reflects how difficult it can be for people at a great distance from a war or conflict to fully empathize with those who are living through it. As I experienced the war in my homeland from almost 8,000 miles away in South Bend, Indiana, I felt a responsibility to illuminate this quarrel for the non-Ukrainians around me. To do so, I had to find the right words and rely on their power. But, where would I find such potent words?

Why are words so important in describing war? There are experiences in our lives so overwhelming that they can overtake our whole being and make us powerless and feeble. The use of words to articulate such experiences gives us back our agency, restores our subjectivity, and reinstates a sense that we have control of our own lives. Putting our experience into words can become a powerful tool of resilience in times of war. The experience of war inflicts a unique trauma that leaves everyone enfeebled and exhausted. We are forced to endure a lack of rational explanation and understanding, confusing and contradictory political messages and conspiracy theories attempting to explain the aggressor’s actions, mentally disturbing quests of figuring out “the bigger picture,” and, worst of all, the death and suffering of loved ones.

Words restore the people’s power. They restore strength and the ability to deal with the ineffable reality. We master the truth, the trauma, which is greater than ourselves, through articulation, by voicing the experience for which no pertinent terms are left. In this way, words humanize and restore agency, allowing one to feel like a complete person again.

It is so out of the order of our usual way of being that any conceptual representation of the war seems incapable of doing justice to the truth, to lived experience. This is where poetry comes to the rescue.

As words can be either iconic or abstract, they can either reveal reality or obscure it. When it comes to a reality that transcends our understanding, we lack suitable conceptual tools to put it into words. No human words, which reflect our finite experiences, are fit for describing the infinite God, so it is no wonder that the religious mind tends to rely on metaphors and poetry to express its relationship with the divine. The religious person abandons abstract concepts and turns to iconic metaphors to speak and write about God. Just like icons, as sacred images, reveal rather than represent the metaphysical God, poetry uses words in iconic ways to disclose rather than describe the indescribable reality.

The war, which imposes its inhuman reality, inflicts incredible suffering on ordinary people and transforms human lives into a permanent “border situation”; people living through war exist in a liminal space. It is so out of the order of our usual way of being that any conceptual representation of the war seems incapable of doing justice to the truth, to lived experience. This is where poetry comes to the rescue. Like any genuine art, it is not meant to represent reality or explain it. It does not invite its addressee to engage in an interpretation but acts upon the person and makes one see more, hear more, feel more.

“War is not a metaphor,” said Ukrainian poet Halyna Kruk during the opening of the Berlin Poetry Festival in June 2022.

“Metaphors don’t work against men with machine guns. … There’s no place for poetry when you can’t approach the destroyed basement of a high-rise…but you can hear your children and grandchildren screaming from under the rubble, and you can do nothing to help them. … This is not a metaphor. … War makes everything so crystal clear that there’s no room for poetry.”

There is much truth in Halyna Kruk’s words. Metaphors that wimple, cover up reality while relying on symbolic expressions have no place in the stories of those who are enduring the war. But, I believe that contemporary Ukrainian war poetry shows that genuine metaphors do not simplify or embellish the truth, no matter how hard and painful it is. They disclose and expose reality, making sense of it through their own means. As my country endures a war for its very existence, I dare to assume that poetry relying on metaphors, antithesis, allegory, and all other possible literary means of conveying the truth of things could be one of the few adequate means to articulate the war.

In this project, four young Ukrainian eyewitnesses and four young non-Ukrainian contemporaries of the war came together to articulate the significance of the written language in poetry and prose precisely within the context of the Russian war on Ukraine. The joint work in pairs between students of the University of Notre Dame and the Ukrainian Catholic University built a bridge above the chasm of the lived experience of war and the faraway observation. By focusing on the works of poets and artists, these undergraduate researchers explored the protest, the testimony, the prayer, the witnessing, and the memorialization of the war in poetic words. Through prolonged and close communication between the authors and readers, between the student researchers and coordinators of the project, “Writing the War in Ukraine” enabled the references of the war reality to become intelligible to everyone, regardless of one’s native language, ethnicity, cultural background, or place of residence. As the students’ analysis articulates, this poetry encompasses such complex responses to war as:

- the vivid portrayal of the resilient motherland, its nurturing and protective abilities standing against the danger posed by the enemy to its children;

- the thin line between language of love and hate, when one emotion involuntarily turns into the other under the influence of trauma, taking on a new meaning and form;

- bearing witness to the invasion and making a statement against “the uninvited guests” while showing gratitude to the country’s defenders and commemorating their bravery in evocative songs; and

- the universally shared dual experience of physical separation from loved ones and inner estrangement from oneself.

“Writing the War in Ukraine” builds upon the “Ukrainian Art as Protest and Resilience” project, presented in February 2023. The participants of the current project have just begun to uncover the rich and deep reality of how the war in Ukraine has manifested through the writings of Ukrainian authors. I hope that through this project they have succeeded in their attempt to understand the lived experience of the war, paving the way for others across a bridge of empathy.

This project serves as a reminder that the war in Ukraine is far from a tragic memory; it continues to be someone’s everyday and immediate reality, even right now as you are scrolling through these pages.

View the Exhibits

The (un)Known Soldier

Poems by Serhiy Zhadan and Pavlo Vyshebaba, research by Abigail Keaney and Halyna Tuziak

Bodies of Earth

Poems by Anna-Maria Osadchuk and Halyna Kruk, research by Bohdana Yakobchuk and Jake Miller

Language of Love/Hate

Poems by Artur Dron and Halyna Kruk, research by Andriana Opryshko and Lindsay Burgess

Invasion

Poems by Mia Ramari and Tember Blanche (Oleksandra Ganapolska and Vladyslav Lagoda), research by Anna Gazewood and Yuliia Sokolenko

Sofiia Dobko, originally from Lviv, is a 2023 graduate of Ukrainian Catholic University, having received a bachelor's degree in philology. She is no stranger to Notre Dame. Last year, Sofiia spent the spring semester studying at Holy Cross College and took part in the exchange program at the University of Notre Dame in the fall. She also worked as an office assistant with the Kroc Institute for Peace Studies and the Keough School of Global Affairs this summer. Being keen on linguistic studies and visual art, specifically drawing and painting, Sofiia believes that their combination can effectively convey the message about the war experiences of the Ukrainian people to the international community.

About this Project

This project had two sources of inspiration. To begin with, this exploration of the written word as an artistic response to the war in Ukraine builds upon a previous Nanovic Institute-led undergraduate research project, “Ukrainian Art as Protest and Resilience.” Launched in February 2023, this project examined how Ukrainian visual artists have given expression to their experiences, emotions, and voices of protest. Secondly, in April 2023, the Nanovic Institute and the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies at the Keough School of Global Affairs, co-sponsored a panel discussion of the poem “мама” (“Mother”) from the chapbook Деякі вірші (Some Poems) by the Ukrainian poet Halyna Kruk. This discussion of “мама” and Kruk’s wider body of work inspired questions about the directness of war poetry, which Kruk describes as “a poetry of emotional fact,” and the ways in which the written word has allowed Ukrainian writers to “bear witness to their own existence.” Kruk’s reflections are a charge to listen, read, and share Ukrainian war writing.

A few weeks into this project, the student researchers were reminded of the urgency of this call by the news that the Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina had been killed by a Russian missile while at a restaurant enjoying dinner with friends. Celebrating her life, the New Yorker described Amelina as “a gifted novelist who put fiction aside to devote herself to documenting the atrocities of Putin’s war.” In the final years of her too-short life, Amelina bore witness to her own existence and that of her fellow Ukrainians. “Writing the War in Ukraine” aims to highlight Ukrainian war poetry, reflecting upon the art form as a direct expression of the trauma of wartime and an opportunity to testify to one's humanity amid the most inhumane circumstances.

Perhaps the most important dynamic underpinning this project is the collaboration between undergraduate students at the University of Notre Dame and Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU). For almost twenty years the Nanovic Institute and UCU have collaborated on programming and mission, particularly through the Catholic Universities Partnership. Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Nanovic Institute and the University of Notre Dame have stood in solidarity with their friends in Ukraine, which included welcoming UCU undergraduates to Notre Dame as exchange students beginning in the fall of 2022. This project brought four Notre Dame and four UCU students together virtually during the summer months of 2023, pairing a student from each university to work closely together to identify sources, devise themes, and write analyses. The Nanovic Institute is immensely grateful to these students for their commitment to the project and their sensitive and generous approach to each other.

This project owes a debt to the work of editors and translators such as Amelia Glaser and Askold Melnyczuk, and projects such as Words for War (edited by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky). Their work has been essential in giving English-speaking audiences access to the most recent Ukrainian writing. More directly, this project would also not have been possible without the contributions and insights of faculty and writers in the U.S., Ukraine, and Ireland. At Notre Dame, Emily Wang, assistant professor of Russian, and Tetyana Shlikhar, assistant teaching professor of Russian, helped inform the scope of this project, while Halyna Protsyk, director of the International Academic Relations Office and lecturer in political science at UCU, played an important part in envisioning and facilitating the ND-UCU student collaboration. The Nanovic Institute is also immensely grateful to three writers who attended Zoom sessions with the students, sharing their insights on the craft of writing, the challenges of translation, and the political and moral importance of artistic expression. We extend our gratitude to Askold Melnyczuk, Julie Morrissy, and Darina Sikmashvili.

Suggested further reading

- Victoria Amelina, “Nothing Bad Has Ever Happened,” Arrowsmith Press.

- Charlotte Higgins, “For Ukrainians, poetry isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity during war,” The Guardian, December 9, 2022.

- Ilya Kaminsky, “Ilya Kaminsky on Ukrainian, Russian, and the Language of War,” LitHub, February 28, 2022.

- Halyna Kruk, “I wish that poetry could really kill: Halyna Kruk’s statement in Berlin,” PEN Ukraine, June 20, 2022.

- Stephen Marche, “‘Our mission is crucial’: meet the warrior librarians of Ukraine,” The Guardian, December 4, 2022.

- Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky, eds. Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine (wordsforwar.com), Boston and Cambridge, MA: Academic Studies Press and Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, 2017.

- Askold Melnyczuk, “For the record: conversations with Ukrainian writers,” AGNI and YouTube, May 2022.

- Lesyk Panasiuk, “In the Hospital Rooms of My Country,” The Atlantic, May 8, 2022.

- Ostap Slyvynsky, et. al., “A war vocabulary: Displaced Ukrainians share fragmented stories of loss, trauma, and absurdity,” Document, June 9, 2022.

Introduction by Sofiia Dobko.

Project leadership and section introductions by Sofiia Dobko, Abigail Lewis, and Gráinne McEvoy.

Online exhibition produced by Keith Sayer.

Project funding and direction provided by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, part of the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame.

Special thanks to Taras Dobko, Askold Melnyczuk, Julie Morrissy, and Darina Sikmashvili.

Header image: “Words” by Kateryna Kosianenko, oil on canvas, 2022. Image used with permission from Kateryna Kosianenko.