Language of Love/Hate

By Abigail Lewis

War transforms and even ruptures the meaning of words. In the context of the war in Ukraine, war has demanded the emergence of a particular vocabulary and an immediacy of language that can testify directly to the reality of war experiences. In the project, Dictionary of War, Ostap Slyvynsky records the transformation of words through stories shared by refugees at a Lviv train station. One such vignette, “Beauty,” underscores the danger of beauty at a time of war: “Beautiful things, people, relationships they don’t exist to inspire. They exist to be annihilated. Not for admiration and loving touches, but for pain.” In her 2022 address to the Berlin Poetry Festival, Halyna Kruk insists that war demands an immediacy of language, not metaphor, that can testify directly to its reality. “No metaphors work against an armed soldier," Kruk stated, “No poetry can save you from a tank that has run over your car as you are trying to take your kids away from the war.” The problem Kruk discusses is that this war requires a directness of language to testify to the existence of those it affects and to the horror of their experiences.

Both poems in “The Language of Love/Hate” were written in the context of Russia’s escalating aggression toward Ukraine, leading to the launch of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Kruk has lived through and written about many experiences of war in Ukraine, stretching back to the annexation of Crimea in 2014. 22-year-old Artur Dron, a soldier in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, visualizes his experiences as a combatant in the current war in Ukraine. Kruk wrote “у моєї мови любові вибиті зуби” (“My love language has broken teeth”) in 2020 before Russia’s escalated invasion gained worldwide attention in 2022. Even at this point, many Ukrainians were angry, frustrated, and upset about Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine, and at the lack of solidarity or effective strategic support demonstrated by the international community. In contrast to her 2014 poem, “мама,” which is more subjective and metaphorical, Kruk’s more recent work, particularly since 2022, employs a directness of language to testify about and against the war. Her writing shows how the meanings of love and hate have become entangled. Amid the suffering of war, relationships once overflowing with love, such as that between a father and mother and their son, have triggered an outpouring of its corollary — hate — directed at those who have broken Ukrainians’ lives and hearts. In Dron’s “Перше до коринтян” (“The First Letter to the Corinthians”), love both threatens and protects life, manifest in a willingness to sacrifice oneself for the nation. This love language is not, as Andriana Ophrysko writes, “beautiful and harmonious.” For Dron, love gives soldiers a reason to fight, love spurns bonds with fellow soldiers, and importantly, love compels him to record their stories and sacrifices within national memory. Both poems stage how the language of love takes new forms and meanings as a result of war.

View the Exhibits

The First Letter to the Corinthians

Poem by Artur Dron, translated by Hanna Leliv.

My love language

Poem by Halyna Kruk, translated by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk.

Lindsay Burgess is entering her senior year at the University of Notre Dame. She is from Roswell, Georgia, and is studying science-business and German with a minor in European studies. On campus, she works as a manager for the Bengal Bouts/Baraka Bouts Boxing Clubs and will serve as this year's Director of the Holy Half Marathon. Although this is her first time working on a research project with the Nanovic Institute, she has previously participated in the Nanovic Institute’s Serving (in) Europe Service Learning Internship in Sofia, Bulgaria. She has also received funding through the Nanovic Institute to complete a summer internship in Heidelberg, Germany, at Caritas Heidelberg.

Andriana (Andy) Opryshko is a senior cultural studies student at Ukrainian Catholic University. She lives and studies in Lviv, Ukraine. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, she volunteered with the refugees coming from the frontline territories, which made her interested in how Ukrainians will remember the war on the collective level. Her research interests at her home university are spots of the dark tourism and sites of memory of the Russian war in Ukraine. However, she is interested in all the ways memory forms and manifests itself during the traumatic events of this war.

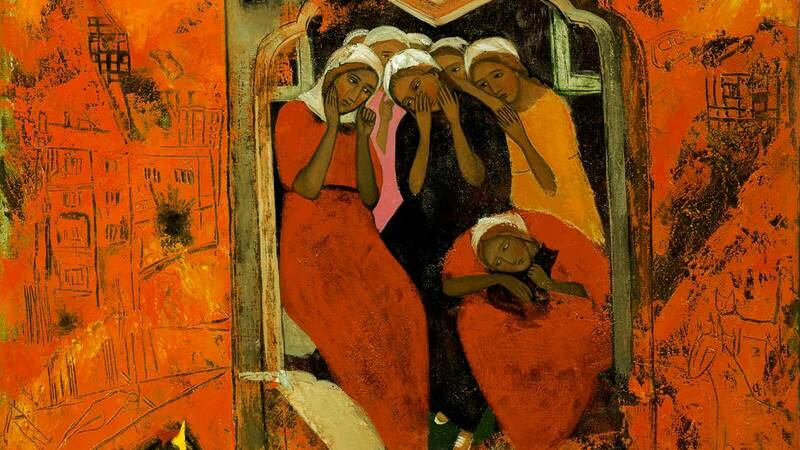

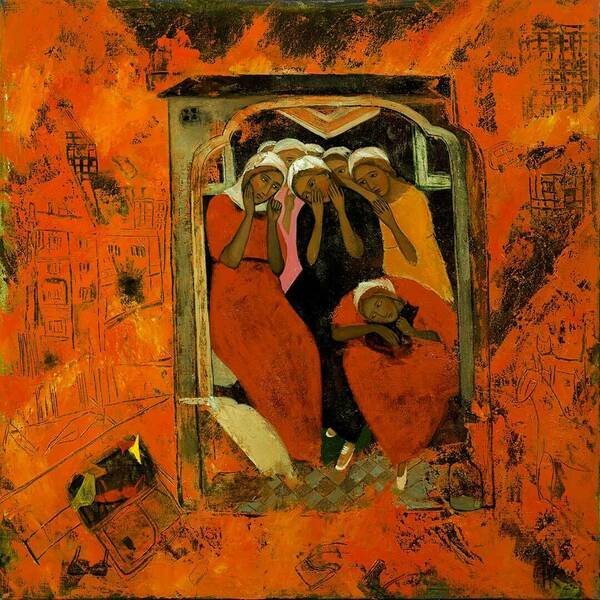

Header image: “Shelter” by Kateryna Kosianenko, oil on canvas, 2022. Image used with permission from Kateryna Kosianenko.