Ukrainian Art as Protest and Resilience: An Introduction

By Yaryna Pysko MGA ’24

To mark the first anniversary of Russia’s expanded invasion of Ukraine, this exhibition brings together artistic expressions of protest and resilience. This art helps us to take stock of the past 12 months and consider the ways in which the war has become ingrained in the everyday life of nearly 40 million people.

The Nanovic Institute for European Studies, part of the Keough School of Global Affairs, and the students of the University of Notre Dame invite us to commemorate Ukraine’s resistance in the exhibition “Ukrainian Art as Protest and Resilience.” The exhibition presents a series of works, created by Ukrainian artists during the war, accompanied by analytical insights provided by students who conducted research during the 2022-23 winter break. The exhibition showcases different formats, including digital, sacred, and street art, music, fashion, and art by Ukrainian children.

The exhibition is a chance to witness the creation of contemporary Ukrainian art as war became an integral part of day-to-day reality. It provides a lens through which one can take a peek, from the point of view of Ukrainian artists and their allies, at the new routine and adjustments Ukrainians have made to accommodate the realities of war. These artists reflect the emotions of ordinary people, many of whom suffer through unimaginable atrocities.

Because art has become a coping mechanism, a lot of these works transmit Ukrainian’s grief as they confront the loss of loved ones who died on the battlefield, during targeted civilian attacks, or during terror in the occupied territories. Their homes have been destroyed by russian missiles, forcing many families to flee abroad in search of safety. Those who one morning found themselves under occupation, had to gather the remnants of their homes, their lives and transit thousands of kilometers through russian filtration camps and bypass several countries to return to Ukraine.

Photograph by Marta Syrko, from her project on bodies physically and emotionally scarred by the war in Ukraine. Syrko writes "I hope to spread a message of hope and resilience, showing that it is possible to find beauty in the aftermath of tragedy." Used with permission from the artist.

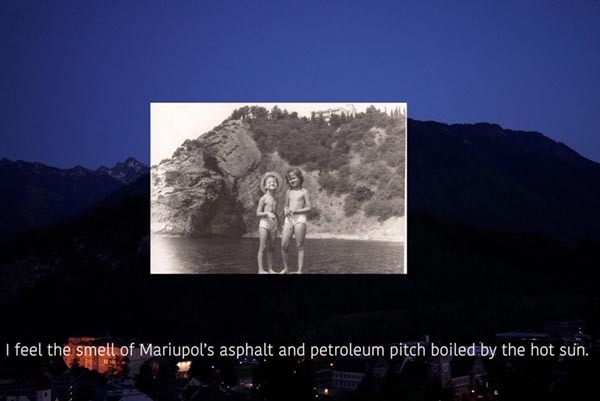

Artists often use familiar landscapes to portray the feeling of nostalgia and longing for the home that has been stolen from them. Zoya Laktionova transmits this nostalgia in the video “Remember the smell of Mariupol,” while Dariia Kuzmych’s photography engages the viewer in a warm atmosphere of family reunion amidst the turbulence of war. Art has become a coping technique and a safe space for children, who are spending their childhood in camps for internally displaced persons, hospitals, and bomb shelters as presented in a drawing by Alina Volochyk, one of many collected into a digital exhibition of children’s war art.

Some of the artwork reflects the intense anger that fuels Ukraine’s resistance. People understand that Russia is waging a war that aims to exhaust the Ukrainian people into submission and that in order to resist, every member of society contributes to the victory in their own way. From young children helping to clean up after the shelling to elderly people baking food to send to the frontlines. Brave men and women take up arms and weapons and join the battlefield to face the enemy because, as Cossacks chanted when the first sword was drawn for the independence of Ukraine in the 17th century, this is a fight for “Freedom or Death.” In the occupied territories, people risk their lives when they engage in partisan warfare. They bury Ukrainian flags in their backyards in hopes of one day proudly wearing them when they are liberated by Ukrainian soldiers.

The artwork in which sacred or historic figures are portrayed holding weapons in their hands points to the centuries-long fight for freedom, culminating in the present tense. Artist Ivanka Siolkowsky presents Saint Olha of Kyiv holding a Javelin, connecting the past and the present in the fight for a future. The message of resistance is spread by the artists Oleksandr Klymenko and Sofia Atlantova who challenge the conventional sacred art techniques by painting icons, a feature natural to the Ukrainian household and rooted in the nation's Orthodox Christian heritage, on the ammunition boxes discarded in the battlefield. With public buildings as their canvas, C215 (Christian Guemy) and Nikita Kravtsov celebrate the fight for liberty, connecting cultures and time periods under one cause. The unity of the Ukrainian nation and hope to endure the struggle are evermore present in contemporary art.

In the context of war, Ukrainian art has become one of the primary arenas for the deconstruction and eradication of dominant Soviet narratives. These interpretations of history, heritage, and nationhood have been imposed on Ukrainian society and culture through policies that amount to colonization and forced assimilation across generations.

The Ukrainian fashion, music, and publishing industries have been transformed by the rediscovery of traditional Ukrainian culture. Artists have incorporated the traditional motif of wheat to symbolize both Ukraine’s agricultural endowment and the trauma of Holodomor (1932-33), a man-made famine aimed at the eradication of the Ukrainian nation during the USSR’s Stalin era. Natural elements, such as sunflowers, poppy flowers, and periwinkle are consistently represented in the recent lines of Ukrainian fashion brands Etnodim and Bevza. Vyshyvankas, a traditional garment, have received a renewed wave of popularity, especially the ancient vyshyvankas, the images of which were gathered in expeditions in the second half of 20th century. Artists have also rediscovered traditional art techniques, like Varvara Logvyn, who uses Petrykivka painting to decorate anti-tank hedgehogs and manifest the strength of Ukrainian culture, which survived Russian colonization and suppression under totalitarian regimes. The feeling of pride in being Ukrainian fuels the resistance against aggression and genocide with some Ukrainians expressing this pride on their bodies, such as in patriotic tattoos designed by Sandra Sukhetksa and numerous tattoo artists across Ukraine. This is also a time of rediscovery of folklore that creates a connection to ancestors through ancient songs, sounds, and words. Music cannot be silenced even in the bomb shelters, where Vera Lytovchenko has performed "Ніч яка місячна” (The starry night). Ukrainian national identity is revived from the ruins of the czar’s empire and GULAG, with art being one of the battlefronts.

The resistance of the Ukrainian people has won the hearts of many. February 24, 2023, the anniversary of the invasion, is also referred to as 389 лютого, the 389th of February, a reformulation of the date that Ukrainian citizens have adopted to signify their commitment to protecting their freedom and the freedom of the whole democratic world. Russia’s attempt to destroy the Ukrainian nation has failed, as it did almost a century ago during both World Wars, the Holodomor, the Great Purge of 1937, and the Executed Renaissance, and the horrors of the GULAG. Today, the Russian media praises Putin’s ambitions, calling for the cleansing of Nazism not only from Ukraine but from the entire European continent.

The brutality of this unjust war is on full display in the age of information technologies. The grandiose visions of the hubristic dictator, wishing to assemble and make the “Great Soviet Union again,” has disrupted the long peace. “Never again” — the lesson the world should have learned after the Holocaust of Europe’s Jews — echoes as the 21st-century world watches a live stream of genocide in the heart of Europe.

This exhibition invites you to process current events under the microscope of individual experiences. The artworks allow you to live the emotions with the artist and take part in Ukraine’s national resistance.

Yaryna Pysko is a Master of Global Affairs student in Governance and policy in the Keough School of Global Affairs and the recipient of a Keough Family Fellowship. A native of Novoyavorivsk in western Ukraine, Pysko graduated from Ukrainian Catholic University with a bachelor’s degree in political science. She has worked as a junior analyst for Civitta, an international consulting company, and on Ukraine’s National Economic Strategy 2030, and on tourism and IT education research projects. Upon graduation, Pysko intends to apply her skills in the post-war recovery process in her homeland.

Read more on the background of this project and further reading on the topic of art as protest.

View the Exhibits

Patriotic Tattoos

Art by Sandra Sukhetska, research by Anna Gazewood ’24.

Remember the smell of Mariupol

Art by Zoya Laktionova, research by Clare Barloon ’24

Petrykivka Hedgehogs

Art by Varvara Logvyn, research by Bella Mittleman ’24

Icons in Digital Art

Art by Ivanka Siolkowsky, research by Emma Acklerly ’23

Fashion as Protest in Wartime

Art by Etnodim and Bevza, research by Felicity Wong ’24

Ammunition Boxes Icons

Art by Oleksandr Klymenko and Sofia Atlantova, research by Jacqueline McKenna ’23

Children’s War Art

Art by Alina Volochysk, research by Libby Eggemeier ’25

A Most Precious Moment

Art by Dariia Kuzmych, research by Michael Ellis ’24

Murals of Resistance

Art by C215 (Christian Guémy) and Nikita Kravtsov, research by Peter Di Re ’23

Music in the Bunker

Art by Vera Lytovchenko, research by Erin Tutaj ’24

Introduction by Yaryna Pysko MGA ’24.

Header image: “St Javelin” by Chris Shaw, acrylic and metal leaf on canvas, completed in March 2022. Image used with permission from Chris Shaw and saintjavelin.com.

Photograph by Marta Syrko, Ukrainian photographer. Used with permission from the artist.

Support from the Nanovic Institute for European Studies provided by: Anna Dolezal, Abigail Lewis, Jennifer Lechtanski, and Gráinne McEvoy.