Bodies of Earth

By Abigail Lewis

On June 18, 2022, poet Halyna Kruk spoke about the role of poetry in the context of the ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Addressing the attendees of the Berlin Poetry Festival, Kruk exclaimed that for Ukrainians, “war is not a metaphor.” She said:

“I dont know of any poetry that can heal this wound. The war is killing us, each of us in a different way, although we may look whole and unharmed on the outside.”

In this powerful speech, Kruk castigated the ongoing reality of war for Ukrainians, a war that began in 2014, and she made a case for the capacity of poetry to bear witness to humanity, human experience, and human existence.

The two poems in “Bodies of Earth” speak to the reality that this war has left no Ukrainian body unaltered, whether physical bodies, the landscape, or the nation. These poems come from two different perspectives and two writers at very different stages of their careers — the internationally recognized Kruk and Anna-Maria Osadchuk, a 20-year-old poet who is beginning her career, fired by her exposure to war just as she enters adulthood. Both Kruk and Osadchuk engage with the impact of the war through the lens of embodiment. For Osadchuk, poetry became a way of expressing her feelings and as a coping mechanism. It was a way to meditate on her existential crisis brought forth by her new reality and a fear of death. Osadchuk shares that poetry is a way of processing and witnessing tragedy. These poems, at once creative writing and testimony, highlight how the war has left visible and invisible scars within Ukraine.

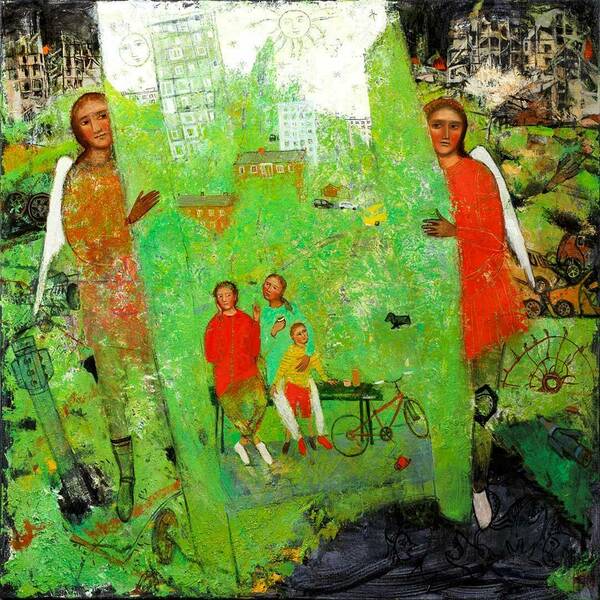

These poems navigate the tensions between the human body and the body of Earth as sites of embodied violence, as well as resiliency and protection. The motherland suffers but it also protects its people and consumes its enemies. In “мама” (“Mother”), Kruk draws on the connection between the mother as family and the motherland as a garden that seeks to nurture, feed, and protect. Osadchuk’s poem, “у монстрів людські обличчя” (“The monsters have human faces”) engages with the duality of the mother/land. Osadchuk personifies Ukrainian land as the soil that “consumes its enemies” and in so doing, fertilizes new growth and new life. For both poets, Ukraine is a nurturing and protective mother, but also a mother enduring the catastrophic tragedy of the loss of her children.

View the Exhibits

The monsters have human faces

Poem by Anna-Maria Osadchuk, translated by Bohdana Yakobchuk, with Sofiia Dobko (editor).

Mama

Poem by Halyna Kruk, translated by Sibelan Forrester.

Bohdana Yakobchuk is a junior at Ukrainian Catholic University studying philology. Originally from Rivne, Bohdana studied biotechnology for two years before deciding to follow her passion for literature and languages. She is interested in studying avant-garde poetry and prose, translation, and gender studies in literature.

Jake Miller is a rising senior at the University of Notre Dame majoring in political science and sociology with a European studies minor. Originally from Buffalo, New York, he now lives in Baumer Hall. He has been fortunate enough to participate in numerous organizations at Notre Dame, including the marching band, wind ensemble, and the Student Policy Network. His academic interests, however, lie in the work of the Nanovic Institute as well as the “Writing the War in Ukraine” project. After graduation, he hopes to apply what he has learned through his coursework and research to a career that intertwines international relations, comparative politics, and memory.

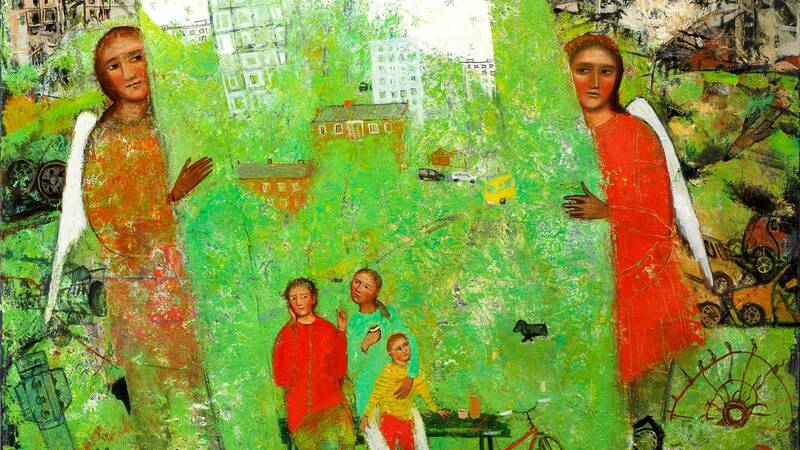

Header image: “Bench” by Kateryna Kosianenko, oil on canvas, 2022. Image used with permission from Kateryna Kosianenko.