Mama

Halyna Kruk

someone stands between you and death — but

who knows how much more my heart can stand —

where you are, it’s so important

someone prays for you

even with their own words

even if they don’t clasp their hands and kneel

plucking the stems off strawberries from the garden

I recall how I scolded you when you were small

for squashing the berries before they ripened

my heart whispers: Death, he hasn’t ripened yet

he’s still green, nothing in his life has been

sweeter than unwashed strawberries

I beg you: oh God, don’t place him at the front,

please don’t rain rockets down on him, oh God,

I don’t even know what a rocket looks like,

my son, I can’t picture the war even to myself

хтось стоїть між тобою і смертю, але, хтозна,

наскільки ще її стане - серце

опиняєшся в місці і часі, де так важливо

щоб хтось за тебе молився

хоча б подумки, хоча б своїми словами

хоча б не складаючи руки в молитві

відриваючи хвостики полуниці, тільки-но з грядки,

згадуючи, як сварила тебе малого,

що товчешся по ягодах, не даєш їм дозріти

шепоче: смерте, він ще не дозрів, він такий ще зелений,

у його житті не було ще нічого

солодшого за ту нехитру немиту полуницю

благає: не клади його, Боже, скраю,

не сип його градом, Боже,

я ж навіть не знаю, як той град виглядає, сину,

я ж навіть не можу собі тої війни уявити!..

Analysis by Jake Miller

The motif of the motherland characterizes many contemporary Ukrainian poems, referring to the idea that the earth below, much like a mother, nurtures and sustains that to which it gives birth. The earth provides human civilization with the natural resources necessary to survive and flourish. Through this motif, Ukrainian poets, including Halyna Kruk and Anna-Maria Osadchuk, portray their country as a motherland, giving life to and caring for its people.

Kruk, an award-winning Ukrainian poet, fiction writer, and scholar, employs the theme of motherland in her poem “мама” (“Mother”), which was written in 2015, one year after the armed conflict that arose in response to the Russian annexation of Crimea. Deeply aphoristic, metaphorical, and somber, Kruk’s poem tells of a mother who anxiously implores God to spare her son from the tragedy of war. The personal nature of the mother’s plea gives the poetic work a human face while allowing others to bear witness to the suffering that the conflict in Ukraine has caused so many. The piece’s reflective tone also differs notably from more recent poetry about the war. As the combat zone has expanded following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine that began in February 2022, poets and other artists have responded by expressing more directly what they see, feel, and experience. Kruk herself has described this as “the poetry of emotional fact.”

Particularly since February 2022, poems like “мама” have become a powerful tool for bearing witness to Ukrainian existence. The poem was the focus of conversation at a recent event on the University of Notre Dame campus. The event, which took place through a collaboration between the Nanovic Institute for European Studies and the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies, explored three translations of “мама — in Ukrainian, English, and Irish — ” as an example of how words on the page can bring to light tremendously personal, yet important, stories that otherwise might not receive the acknowledgment they deserve.

The motif of the motherland, which Kruk alludes to through earthly imagery and metaphor, helps establish “мама” as a personal testament to the blight of war. In the poem, the mother appeals to God’s mercy and asks him to recognize her son’s innocence. She compares her son to an unripe strawberry growing in the family garden, recalling that she rebuked him as a child for squashing the fruits before they had ripened. While ripe strawberries characteristically feature a red coat, unripe ones typically appear green, indicative of unfinished growth and maturity. Much like an unripe strawberry, the mother’s son is still young, still growing, and has yet to reach his full potential.

The mother goes on to state that “nothing in his life has been sweeter than unwashed strawberries.” Compared to unripe strawberries, unwashed berries are incredibly pure, not yet exposed to water and moisture, which only hasten the spoiling process. Her son, who is young, innocent, and pure, is not ready to face the spoiling process. He is not ready to face death. He has so much life yet to live. Unfortunately, death in the combat zone does not always discern between ripe strawberries and unwashed, unripe ones. A mother, however, knows with certainty. She hopes that God, the all-knowing being, can spare her child from the cruel and arbitrary nature of death on the field of battle.

In addition to employing earthly imagery and metaphor, Kruk’s poetic work emphasizes the dualistic nature of the mother who is both earth and human, or as Bohdana Yakobchuk describes it “the duality of mother/land.” On the one hand, the land of Ukraine is akin to a mother, its fertile soil giving life to crops of all kinds, including strawberries. The nutrient-filled soil, sun, and rain work in tandem to cultivate and nourish these crops until they reach maturity. On the other hand, a human mother does the same, giving life to her children and caring for them until they are mature—“ripe”—and can live independently. By portraying the mother in two divergent yet tremendously comparable ways, Kruk accentuates the connection that the mother-narrator and her son have with the earth and the family garden: both land and humanity are precious and deserve the utmost care.

Research by: Bohdana Yakobchuk and Jake Miller

Poet: Halyna Kruk

Translator: Sibelan Forrester

Theme: Bodies of Earth

"Mama" by Halyna Kruk, translated by Sibelan Forrester, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

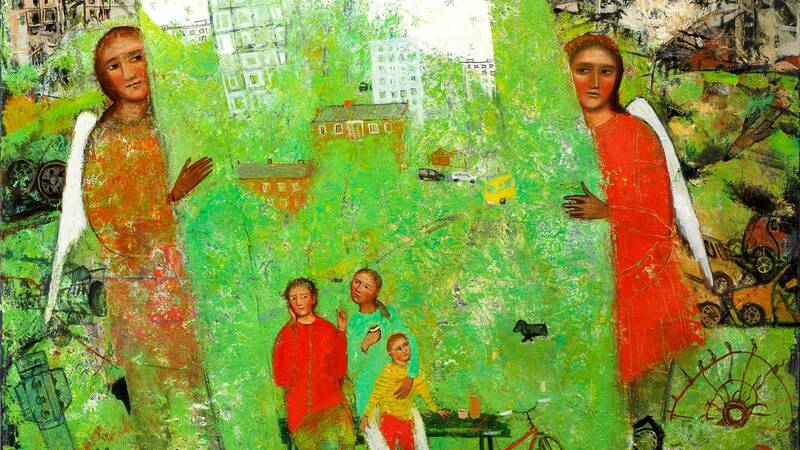

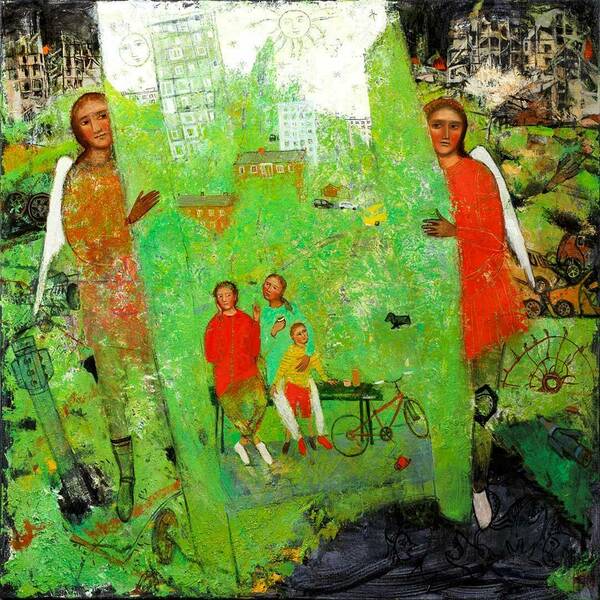

Header image: “Bench” by Kateryna Kosianenko, oil on canvas, 2022. Image used with permission from Kateryna Kosianenko.