Dariusz Skórczewski is Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Associate Professor of Theory and Anthropology of Literature at John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Poland. In the summer of 2022, he was a visiting scholar at the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, sponsored by a grant from the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (NAWA). During his time at Notre Dame, Skórczewski conducted research on a 19th-century diary housed in special collections at the Hesburgh Libraries. Written between 1819 and 1856, the diary belonged to a Polish noblewoman, Pelagia Rościszewska, who was settled in Kievan Governorate. Here Skórczewski shares some of his initial findings and raises the questions that he will consider as this he develops this project.

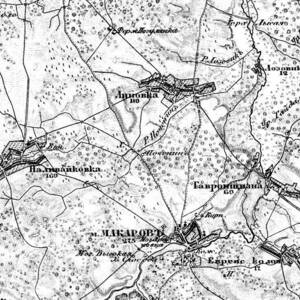

This diary was written by Pelagia Rościszewska, née Zaleska, a Polish noblewoman married in 1798 to Walenty Rościszewski, a member of the well-known Polish family, the Rościszewskis. This Roman Catholic family of Mazovian origin is one of the oldest Polish families with a lineage that continues to today and a long tradition of public service and service to the state. One branch of the family settled in Ukraine in the turbulent 17th century. The Rościszewskis were widely respected, although, at the time that the diary was written, the Ukrainian branch was no longer as wealthy as other major Polish aristocratic families in that part of the former Polish-Lithuanian(-Ukrainian) Commonwealth. Pelagia wrote her diary in her estate in Lipovka, at that time in the Russian-ruled Kievan Governorate, approx. 30 miles west of Kyiv.

The diary portrays the history of a 19th-century family of Polish landowners in Ukrainian lands that were incorporated into the Russian Empire, setting the family’s experience in the rich social, political, and cultural context of the era. Given its size, the time covered in the diary, and the female perspective, Pelagia’s diary is a rare document for its time and an outstanding source of information concerning Polish-Russian relations in the territories of the Commonwealth that were incorporated into the Russian Empire.

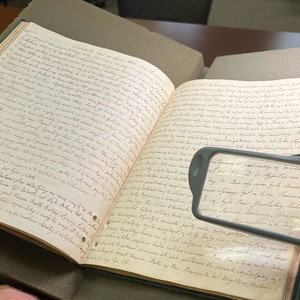

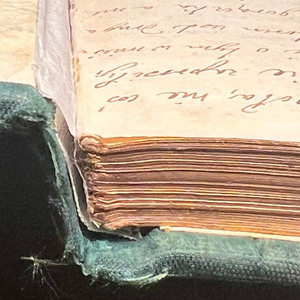

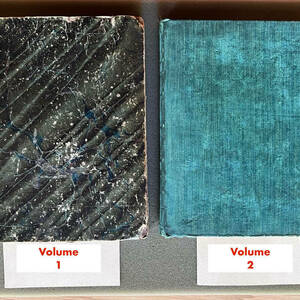

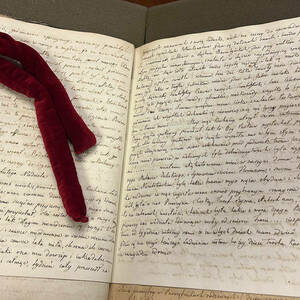

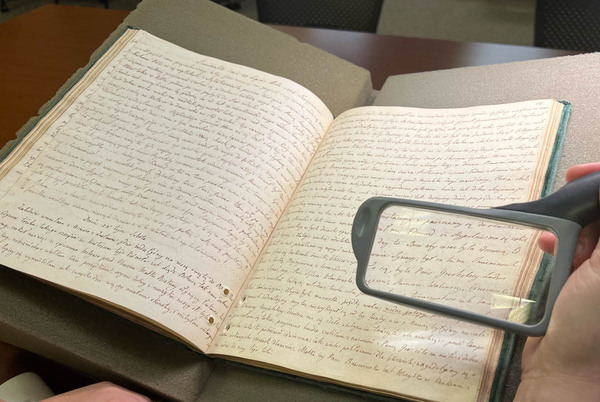

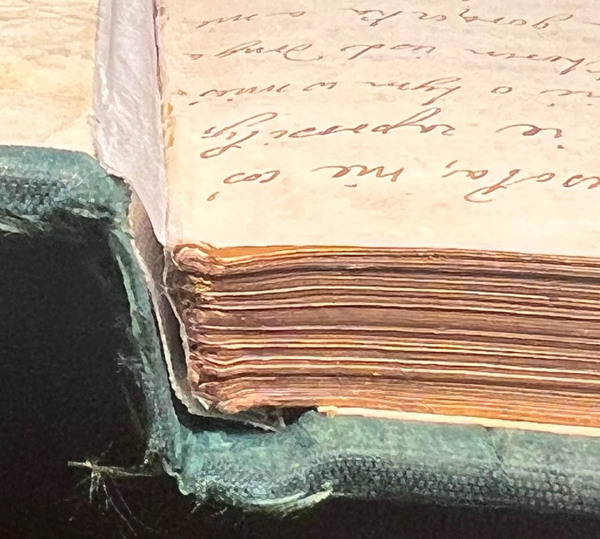

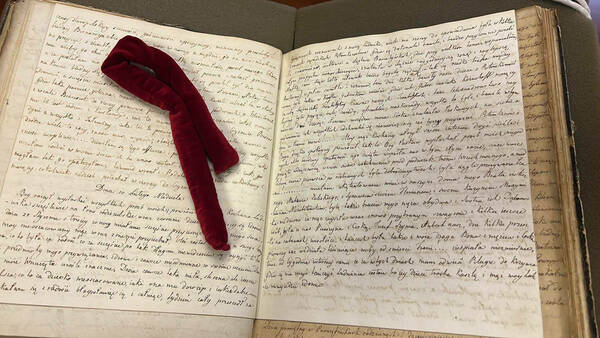

Pelagia’s manuscript consists of two volumes with a combined total of around five hundred pages if it was transcribed to the standard page size we use today (of about 1,800 characters per page). It has been well-preserved and is in excellent condition. The volumes, however, must have been repaired, most likely in preparation for sale, as there are visible signs of repairs to the binding and the area where the cover is attached to the notebook, in order to stabilize the volumes.

Volume one consists of three bound fascicles of 108 sheets in total. It is watermarked and covers the years 1819-1824, 1837-1844, 1848-1849, and 1856. Based on consultation of Tromonin’s Watermark Album, which was published in Moscow in 1844, it can be inferred that the first fascicle was made of an 1818 large mold-dated paper and an 1819 mold-dated writing paper. We can also determine that the second fascicle was made of an 1806 notepaper and that a third fascicle, the one that is of the poorest quality and uses the darkest paper and covers the latest period, was made of an 1832 medium pink mold-dated writing paper. It is still unclear how and when this volume was bound. The volume is made of three fascicles of differing paper sizes, with gilded edges and watermarks, and it clearly differs from the other volume which is fully uniform in size.

Volume 2 is a homogenous fascicle of 105 sheets of woven paper, watermarked, covering the years 1825-1830. It was made entirely of one type of paper, which, again based on Tromonin’s Watermark Album, I can infer was made of an 1818 large mold-dated paper.

Unfortunately, the period of the November uprising of 1830 and the subsequent Polish-Russian war of 1831 followed by massive persecutions and deportations to Siberia is missing from the diary.

My research of the diary raised questions for further research:

- Why are the two volumes arranged in this way?

- Why were the two volumes bound by two different bookbinders, even though the manuscript was intended by Pelagia to be inherited by one person, her daughter Ludwika (Louise Princess Troubetzkoy)?

- Where is the missing volume covering the period 1831-1836?

- How has the manuscript survived the turbulent history of the first half of the 20th century in the area of Central and Eastern Europe that historian Timothy Snyder has referred to as the “Bloodlands?”

A mother’s expression of remorse?

Perhaps the most important question raised by my research on this document is: why did Pelagia write her diary? To address this, I offer the following hypothesis:

As declared on the very first page of the diary, its direct addressee was Pelagia’s oldest child, Ludwika, the wife of a Russian aristocrat, Prince Alexander Troubetzkoy, and her grandaughter Dorota, Ludwika’s first daughter. Pelagia started writing the diary (which she herself termed “weekly”) in 1819, the very same year in which Dorota was born. From reading the diary it is very clear that from among Pelagia’s five beloved children, Ludwika occupied a special place in Pelagia’s mind and was continuously prioritized as the object of her constant attention and loving care.

Was the diary just an expression of Pelagia’s personal natural preference and affection as a mother? While thematically rich and abounding in details concerning family relations and the social practices of the Polish and Russian upper class in the Ukrainian lands, religious, cultural, and economic life, the diary’s internal focus, its underlying layer, and its very fabric is Ludwika’s (untold) story, part of which is known from external sources.

According to numerous anecdotes, Ludwika was one of the most attractive Polish women at that time not only in the Kievan Governorate but in the whole of Ukrainian lands. Poets wrote poems in praise of her exceptional beauty, although it is most likely that no trace of her visual representation has been preserved. Before Pelagia started her diary, Ludwika drew the attention of Tsar Alexander I during his stay in Ukraine, probably in Zhytomyr around the time of the Napoleonic wars.

According to one anecdote, her father Walenty Rościszewski took the initiative to throw his own daughter into the arms of the Tsar. In one version of that story, Walenty’s motive was to use Ludwika for political purposes, for the “Polish cause,” in a manner similar to the role played by Maria Walewska, the famous mistress of Napoleon Bonaparte. How true this story is remains uncertain, and Pelagia who maintains high ethical standards throughout her diary does not mention that episode at all.

Two facts, however, are confirmed by external references. First, Walenty was awarded the Order of St. Anna (Ordien Sviatoy Anny), a Russian Imperial distinction from Tsar Alexander. According to a rhymed anecdote, he received it for handing his daughter over to the Tsar: “Za Pannę dostał Annę” (“He was granted the Anna for the maiden”). Second, soon after this episode, the Tsar handed Ludwika over to his fligeladiutant, or aide-de-camp, Prince Troubetzkoy (another Alexander) and charged him to marry the reputed beauty. This all took place not long before 1819, the departure point of the narrative in Pelagia’s diary.

More facts on the later developments can be found in the diary:

- As noted above, Pelagia started writing her diary in 1819, the same year that Ludwika, now Princess Louise Valentinovna Troubetzkoy, gave birth to Dorota, known as Princess Daria Alexandrovna Troubetzkoy, who later married a descendant of another famous Polish noble family, Rozesław Rylski.

- At some point between 1830 and 1837, on one of his frequent visits to Russia, Ludwika’s husband Alexander Troubetzkoy found himself another woman, Vera Alexeevna Igumnova nee Somoff. Born in 1821, she was over twenty years younger than his wife.

- What happened next can be easily guessed: Ludwika was led up the garden path by her husband who perfidiously tried to renounce his marriage and become released from any financial obligations.

- From that time on, a substantial part of the diary was devoted to the steps taken by Pelagia and Walenty, via their Russian contacts and on behalf of their daughter, to request that Tsar Nicholas force their son-in-law Alexander to divorce Ludwika legally rather than abandoning her as if she had never been his wife.

- Through the mediation and intercession of Alexander’s youngest brother, Prince Nikita Troubetzkoy, this goal was eventually achieved.

This sad story is but one of many threads in Pelagia’s diary and supports my claim that Ludwika’s role in the diary is critical to a deeper understanding of why the diary was written. On the very first page, Pelagia wrote:

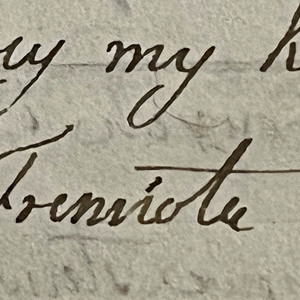

“My dearest Daughter and Grand Daughter (if God keeps her alive) will read this writing some day, they will see in it my manner of judging, feeling…”

This is Pelagia’s direct answer to my question: she wanted to convey to her daughter her most intimate experiences, perceptions, worldviews, and value system, but due to that unfortunate context, and because Pelagia was a person of high ethical standards, it is difficult to believe that as Ludwika’s mother, she would have agreed with what happened to her daughter. Pelagia would never sacrifice her daughter for any sake, even for the most sacred national case.

Hence, I claim that Pelagia’s diary is a materialized yet non-verbalized expression — proof, in other words — of Pelagia’s remorse for not acting strongly enough to prevent her husband from throwing Ludwika into the arms of the Tsar, which resulted in Ludwika’s failed marriage and its consequences for her children. Among all the possible reasons why this diary was written, this may have been the most direct and most intimate impulse for Pelagia to write it the way she did.

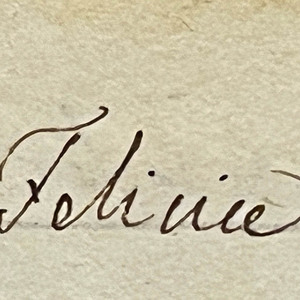

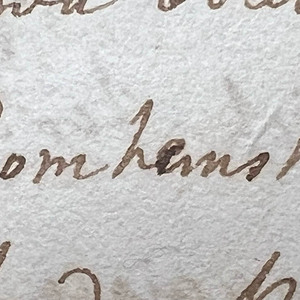

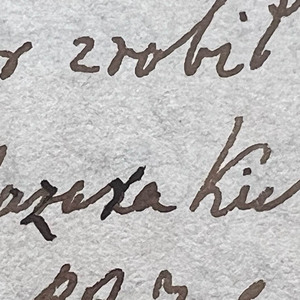

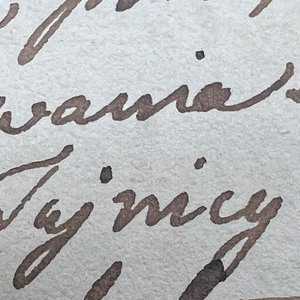

I must also resolve some typographical problems: in particular, identifying the names of people and places. As is typical of a manuscript of a diary or a memoir, Pelagia’s diary contains hundreds of names of people and places, all of which need to be deciphered. This task is made more difficult by the fact that sometimes these names are misspelled or spelled in a way that diverge from their contemporary spelling. In the gallery below, I have included images of some names of people and places that I have not yet identified. I welcome any suggestions (email dareus@kul.pl) from anyone who might recognize these names.

For a more detailed view of the diary, plus descriptions, click on the gallery below.