Margaret Sutton is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Notre Dame specializing in environmental and cultural history. Over spring break of 2023, with the support of a Nanovic Institute research travel grant, she traveled to London to conduct preliminary dissertation research on the English ski pioneer Sir Arnold Lunn. Through Lunn, Sutton seeks to understand how Englishmen sought the vertical frontier to navigate modern societal changes and discern their religious beliefs.

In her Presidential Address to the American Historical Association in 2009, Gabrielle Spiegel posed two questions: “If not from the nation, society, or domicile, from where does social identity derive its shape?” More so, “If we are at once citizens of the world and citizens and subjects of specific nations, how are the contradictions implicit in this form of multilocality negotiated on both the individual and the collective level?” My archival research on Sir Arnold Lunn centered around similar questions. How, I asked, did mountains — and, specifically for Lunn, the Swiss Alps — emerge as frontiers for refashioning and securing individual and collective identity in twentieth-century Western Europe? More so, how do the Catholic conversion and eccentric character of this figure, often referred to as the British “ski pope,” help us make sense of religious shifts and cultures of remembrance during the First and Second World Wars?

By and large, scholars of Western Europe have paid little attention to the significance of alpine sports in their studies of modern Christianity. Similarly, historians of mountaineering and skiing have overlooked the religious dimensions of athletes’ identities and experiences, generally interpreting mountain sports as secularized, extra-institutional venues for meaning-making that reflect a decline in the influence of religion in the modern age.

We cannot make sense of either Christianity or mountain sports without the other ... For some women and men, the mountains became a new church entirely.

We, however, cannot make historical sense of either Christianity or mountain sports without the other. Many of the first self-proclaimed European mountaineers were Victorian clergymen; others, Catholic popes and priest-scientists. For some women and men, the mountains became a new church entirely. Understanding the rise of mountain sports requires attention to its participants’ religious anxieties and desires, and understanding broader religious and secular battles in Western Europe requires attention to how these contests played out in the mountains.

The integrative role of the Swiss Alps for Lunn

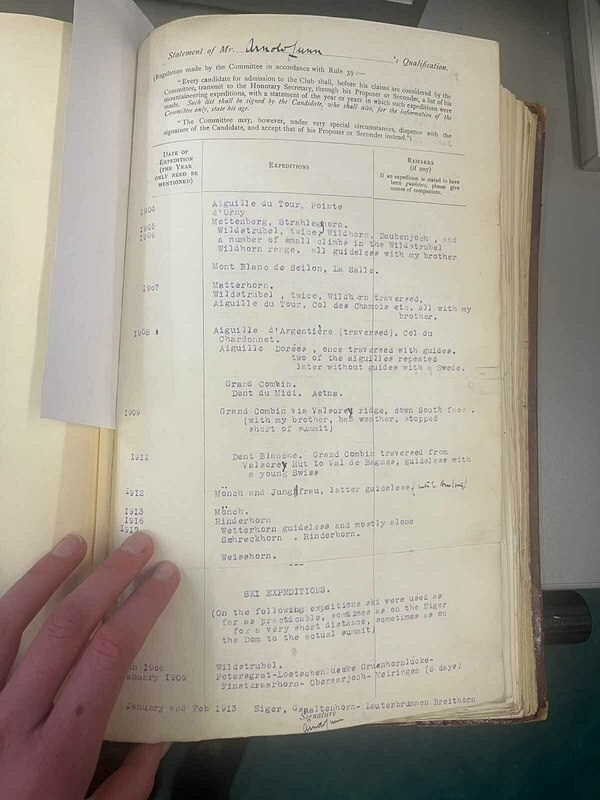

Over spring break, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to explore this co-constitutive relationship. Visiting three archives in London and the surrounding area, I learned about the internal and external life of Catholic convert and ski pioneer Sir Arnold Lunn. In almost all the sources I investigated –– including Lunn’s contested application to join the London Alpine Club, his 1938 memoir, Now I See, his reflections in his British ski club’s journal, The Kandahar Review, and his correspondence with students as a visiting professor of apologetics at Notre Dame –– I found one theme particularly evident: Lunn was preoccupied with Switzerland and its mountains. Additionally, I noticed that he used the Swiss Alps in two fundamental ways: to discern his sense of self and to articulate his political and religious beliefs to others. From his first days skiing in Chamonix to his last on the slopes above Mürren, Lunn looked up in order to look down, turning to the mountains for a better vantage point from which to view God, himself, and the links that bound Europe together.

The Swiss Alps not only inspired Lunn to abandon his materialist worldview but also provided him with a stable site of memory to bind his identity and faith in a world marked by ideological choice and rupture. The mountains, along with the tradition of the Catholic Church, allowed him to see his world in terms of continuity rather than change. In Rome and Switzerland, he found stable monuments impervious to shifting social mores and the passing of time. They each offered hope in the face of Lunn’s greatest fears: the degradation of society, diminishing faith in supernatural truths, the destruction of war, and even his own mortality.

Specifically, I found a paradox at the heart of Lunn’s character. In sources held at the London Alpine Club, he expressed a longing for orthodoxy. At the same time, he wished to prove himself distinct. On the one hand, he characterized himself as a conservative anti-humanist who admired the “ancient consistency and pastoral simplicity of mountain life.” On the other, he was competitive and sought to be original in his faith, ski career, and writing. In many cases, the mountains helped him reconcile these oft-contradicting desires for belonging and authenticity. Throughout his life, he worked to fit his intellectual, religious, and athletic work within a pre-modern tradition while setting out to carve new paths in ski and academic communities. Climbing on, skiing in, and writing about the Alps allowed him to assert his individuality. At the same time, he secured his permanent place within an enduring community of believers and mountain lovers. He wrote his personality and character into the landscape, immortalizing himself in the tradition of the Kandahar Ski Club and other skiing organizations.

Faith and the mountains: New perspectives and questions

My research on Lunn calls into question scholars’ treatment of mountaineers and skiers as predominantly godless actors and of mountaineering as simply a replacement religion. Lunn’s religious beliefs permeated his writings about the mountains; and, in turn, his love for the mountains shaped his faith. By reading book reviews, obituaries, and minutes from club meetings, I also found that Lunn’s conversion experience was not anomalous. His books, actions, and character inspired many of his contemporaries to follow a similar path. For Lunn––and, it appears, for several others––the mountains served as conduits for returning to orthodox Christianity.

As I continue to analyze the sources by and about Lunn, I look forward to building on the work of Michael Wheeler in Ruskin’s God (1999), which explored the literature and career of the English writer John Ruskin through a theocentric lens. Conducting archival work on Lunn also inspired further research questions I plan to address in my dissertation. These include but are not limited to studying the intersection of mountain and religious culture in Swiss and Tyrolean Catholic communities.

In addition to advancing my historical understanding of Sir Arnold Lunn, my trip to London allowed me to connect with current members of and archivists at some of the clubs Lunn founded and actively participated in. I look forward to cultivating these relationships in the coming years and with future research trips. These interactions helped prompt several new research questions. Going forward, I am particularly interested in exploring the relationship between the Vatican and mountain sports in the twentieth century and how Lunn engaged with avid skiers such as Pope John Paul II and Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati.

I recognize that none of this would have been possible without the financial support of the Nanovic Institute. I cannot thank the Institute enough for funding my research and, especially, for supporting work that furthers the study of Christianity and mountaineering in the West.

Originally published by at nanovicnavigator.nd.edu on May 19, 2023.