Something has vexed Chinese Catholicism for over four hundred years: communication. From Matteo Ricci’s appearance before the Wanli Emperor in 1601 to Pope Francis’s agreement with Xi Jinping in 2018, a deep, lasting rapprochement between Roman Catholicism and Chinese culture has yet to appear. Is the religion intractably European? Are respective cultural categories so disparate as to preclude a sturdy middle ground? Missionary evangelists and native Chinese Catholics can provide contemporary answers to these questions. For a historical perspective on the issue, however, one should turn firstly to fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Renaissance humanists. This might seem strange, but it provides the first page in a fascinating and forgotten chapter of early modern history, wherein European scholars sought to understand themselves in relation to other peoples and places.

Our story begins not with the Jesuit missions to China, but an Italian recovery of Greek literature. As fifteenth-century humanists translated and edited ancient texts, they looked for an organizing principle, some sort of narrative or concept to tie classical antiquity together. Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), the Florentine translator of the Platonic corpus, developed such a principle: prisca theologia, or “ancient theology.” Drawing on both Patristic and Neoplatonic antecedents, this theory maintained that the best of classical European knowledge did not originate in either Greece or Rome, but in Egypt and Chaldea (modern-day Iraq). To read deeply in Plato, then, was to transcend the boundaries of “western” civilization and participate in a deeper, global tradition.

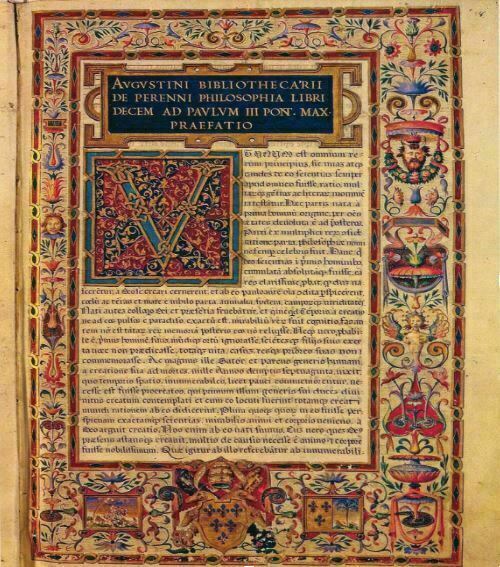

This prisca theologia proved popular. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) and Agostino Steuco (1497-1548) would take up the theory and expand it, with Steuco going so far as to say that every culture possessed fragments of the knowledge given to Adam by God (which Steuco attempted to reconstruct in his work De perenni philosophia). Through the influence of these successors and Ficino’s own scholarship, variations of prisca theologia became a typical way of thinking about ancient philosophy in the 1500s. Even Protestant writers, such as Philippe de Mornay (1549-1623) and Walter Raleigh (1552-1618), adopted the theory with glee. For these early moderns, the greatest wisdom of European civilization derived from non-European sources.

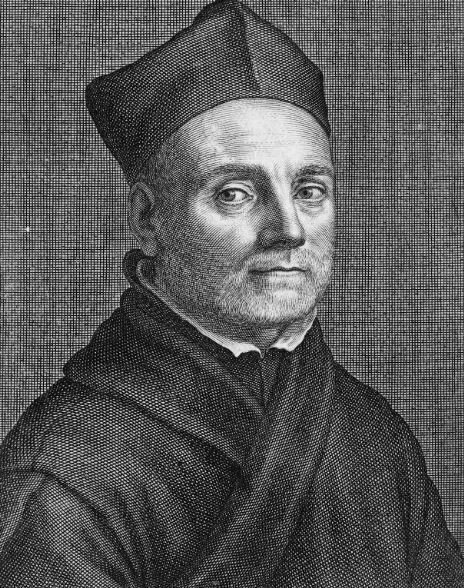

As for the link between prisca theologia and China, there is one key figure: Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). A German Jesuit polymath who taught at the Roman College, Kircher was famous for his capaciousness and loquaciousness, writing on mathematics and physical sciences as much as languages and literature. Ancient Egypt loomed particularly large in his imagination, and in his (in)famous Oedipus Aegypticus, he boasted a “translation” of thitherto undeciphered hieroglyphics. It was a failure, but a spectacular one, and in its references to ambiguously eastern wisdom, Renaissance prisca theologia shines through. As best he could, Kircher rooted around in ancient documents for the ur-source of all knowledge.

This led him to China, whose mission was dominated by the Society of Jesus. Gathering together the reports of fellow Jesuits, Kircher published his China Illustrata in 1667. The work promised a distillation of everything China—language, customs, plants, animals—into a succinct compendium. Like many other Kircherian endeavors, this grandiose synthesis was inaccurate yet influential. Most importantly, Kircher attempted to connect Chinese writing and culture to that of ancient Egypt and thereby grafted the Middle Kingdom into his variation on the prisca theologia. China Illustrata constituted an important shift, taking a technique developed to understand dead civilizations and applying it to a living society.

The “Figurists” would put the Kircherian shift into action. Shaped by the speculations of their confrere, this group of French Jesuits came to China in the 1680s and glossed Confucianism through yet another variety of prisca theologia. As Joachim Bouvet (1656-1730) and his partners told the tale, Chinese civilization derived from Shem, son of the biblical patriarch Noah, and so the Confucian Four Books and Five Classics actually contained antediluvian wisdom. This was not some proto-colonial subjugation of Chinese culture to European categories, but an attempt to establish a hermeneutical foundation upon which Western and Eastern intellectuals could stand as equals, heirs to common, primordial patrimony.

Perhaps naive to us, but not to the Figurists’ Chinese interlocutors. The Kangxi Emperor (r.1661-1722), impressed by these Jesuits’ knowledge and respect for Chinese culture, kept them close at hand and even issued an Edict of Toleration in 1692, recognizing Catholicism legally and thus rewarding a century of hard missionary toil. With imperial legitimization, the Society of Jesus might have established the most robust expression of non-European Catholicism in Early Modernity. Unfortunately, other missionaries objected to the Figurists’ “syncretism,” and as a result of the so-called Chinese Rites Controversy, the Kangxi Emperor quashed the missions in 1721. With the Figurist vision shattered, only a persecuted Chinese Catholicism would endure until the restoration of sustained Catholic missions in the twentieth century.

Though its success was short-lived, the Jesuit use of prisca theologia gives an optimistic answer to our original query. By bracketing any notion of European superiority and deploying an ambitious, cosmopolitan theory of knowledge, early modern scholars were able to place differing cultures in affirming relation to one another. Here at the University of Notre Dame, we often say that “Your Research Matters,” but in the throes of the research process, the end goal is sometimes obscure. This historical episode can encourage and remind us of how crucial scholarly ingenuity can be, using even the seemingly recondite to bridge insurmountable divisions and bring people just a little closer together.

Suggested Further Reading

Brockey, Liam Matthew. Journey to the East: the Jesuit Mission to China, 1579-1724. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Schmitt, Charles B. “Perennial Philosophy: From Agostino Steuco to Leibniz.” Journal of the History of Ideas 27, no. 4 (1966): 505–532.

Stolzenberg, Daniel. Egyptian Oedipus: Athanasius Kircher and the Secrets of Antiquity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Wei, Sophie Ling-chia. Chinese Theology and Translation: The Christianity of the Jesuit Figurists and Their Christianized Yijing. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2019.

About the author

Samuel Roberts is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Notre Dame. He received his B.A. in history from Hillsdale College and his M.A. in history from the University of Notre Dame. His research explores the reception of classical texts and their use in writing histories of philosophy during the sixteenth century, focusing on the work of Vatican librarian Agostino Steuco (1497-1548). His further interests include early modern translation of the Greek Church Fathers, Jesuit missionary strategies in the Americas and East Asia, and the intellectual foundations of religious toleration in Reformation Europe. He has been a Sorrin Fellow at the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture, a Graduate Fellow at the Nanovic Center for European Studies, and a Teaching Fellow at the Notre Dame London Global Gateway.

Originally published by at eitw.nd.edu on February 09, 2024.