After years of careful research, funded in part by the Nanovic Institute, John Deak—Nanovic Fellow and Associate Professor in the Notre Dame History Department—recently published an article on the Habsburg Empire in The American Historical Review. The article, “How to Break a State: The Habsburg Monarch’s Internal War, 1914-1918” (co-authored with Jonathan E. Gumz), examines the downfall of the Habsburg Empire during World War I. In a recent interview with the Nanovic Institute, Professor Deak discussed his paper and his on-going work on the Habsburg Empire.

For those of us who don’t know much about the Habsburg Empire, can you tell us three important things about it?

First, it had been in the center of Europe for a long time before the First World War. It was ruled by a family, the Habsburgs, who had taken possession of lands in Central Europe in around 1273 and expanded their territory. So, the first thing to know is that the Habsburg Empire was a family dynasty that got its name from the Habsburg family.

Second, it was an evolving, modern empire. It evolved for more than six centuries and developed modern state institutions up to the First World War. In fact, this is something that most people who have general knowledge of European history aren’t aware of because it has been largely ignored in the way we tell the story of Europe.

The third most important thing is that it was destroyed in and by the First World War, which sounds like a statement of fact, but it’s not necessarily uncontroversial. For the most part, since World War I, historians and political scientists have made the argument that the Habsburg Empire was in a long-term period of decline. It was not modern and was therefore anachronistic—it could not fit into Europe and the First World War was merely a strong wind that blew a condemned building down. According to the prevailing picture, World War I didn’t kill the Habsburg Empire so much as provide the last nail in the coffin. But I think the First World War actually killed it. It was vibrant, alive, evolving, and reforming, and many of its citizens took part in discussion of its future, a future which would have had to have the Habsburg Empire in it. But after 1918, that possible future was destroyed because of the war.

How did you become interested in the Habsburg Empire?

Family. My last name is Hungarian, and my father’s family emigrated from the Habsburg Empire to Pittsburgh in 1900. The village he lived in, just outside of Pittsburgh, was a multi-ethnic, Habsburg village. The people there were Slovaks, Hungarians, and Ruthenians (or Ukrainians). And my mother’s side of the family is Polish. So, I had a Central European background to begin with.

From an early age, I was interested in history. But when I took European history in high school, I wasn’t taught anything about the Habsburg Empire. I was given a textbook with a big map of Europe before World War I. The biggest country on the map was Austria-Hungary (one of many names for the Habsburg Empire) but the textbook didn’t say anything about it, and my teachers never talked about it. So I started reading about it on my own.

Later, I got to college and more or less the same thing happened. I learned about Europe, but when it came to the biggest country on the map of Europe (besides Russia, which stretched off the map), no one talked about it or even seemed to know anything about it. So I used college to take classes on Eastern Europe and teach myself and write about the Habsburg Empire. I took German history classes and wrote about the Habsburg Empire. I took intellectual history classes and wrote about the Habsburg Empire. I learned German. I started taking Russian and other Slavic languages. I guess I was one of those kids that when I discovered that my curriculum did not teach the history I wanted to learn, I got frustrated and taught myself. And eventually someone gave me a Ph.D. and let me teach it myself. In 2014, for the first time in my life, I stood in front of the classroom in a class on the Habsburg Empire. I had to admit to my students that this is my area of expertise, but it was the first lecture that I had ever been in on the Habsburg Empire.

In your article, you and your co-author argue that an important contributing factor to the fall of the Habsburg Empire after World War I was an internal conflict between state officials, who were trying to uphold the law, and the army, which wanted legal exceptions for military purposes. What’s your favorite example of this conflict?

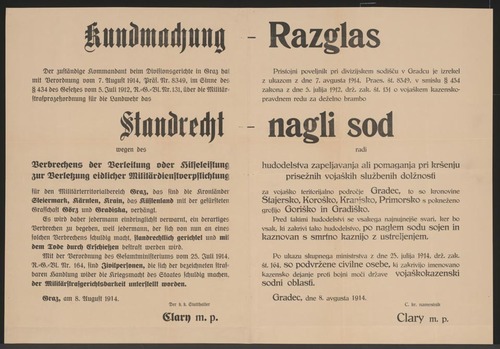

The text of this poster declares Martial Law for the territories in the southern part of the Habsburg Empire. It says that crimes committed against military personnel or against the war-making capabilities of the state will be “tried by special military court and sentenced to death by firing squad.”

The text of this poster declares Martial Law for the territories in the southern part of the Habsburg Empire. It says that crimes committed against military personnel or against the war-making capabilities of the state will be “tried by special military court and sentenced to death by firing squad.”

One of my favorite examples comes from the Southwestern Front between Austria-Hungary and Italy. The commanding general of this front on the Habsburg side was Archduke Eugen, a cousin of Franz Joseph (emperor of Austria-Hungary). In the process of commanding the front, Eugen instructed civilian officials who were in the border region to take down all signage—on official buildings, street signs, private shops, etc.—that were in Italian. His argument was that the troops in his command were fighting against the Italians, and it was demoralizing when they were relieved from the front and had to see signage in the language of the enemy. Of course, what Eugen did not seem to understand was that the Habsburg Empire was multi-lingual, and official signage would be in all of the official languages of the particular province. The province was Tyrol and the official languages were German and Italian. In addition, the signage was constitutionally guaranteed by the 1867 December Constitution. And so the officials didn’t follow the order.

In response, Archduke Eugen complained and tried to punish the officials. Of course, the officials complained to their superiors too. And what we had was a situation where the archduke was complaining up the ranks to the high command and the officials were complaining up the ranks of the civilian government. And it eventually came to a head: the prime minister and the war minister faced off in their own argument. In a series of letters in 1916, the prime minister instructed the war minister to lecture Archduke Eugen (who, remember, was a member of the imperial royal family!) about the importance of the constitution and that any attempt by the military to subvert the constitution would undermine the legitimacy of the state itself. Eventually the archduke had to back down. So, this is a chapter where civilian officials win. But there were lots of chapters where they lose, where the military executed people according to martial law before the civilian authorities could intervene.

Did other countries involved in World War I also have an internal conflict between state officials and the military? If so, what was unique about the conflict in the Habsburg Empire?

Because the First World War was a total war that dragged on for so long, we see militaries reaching further into civilian life than ever before. This happens everywhere. In Germany, it happens slowly. But by 1916, we have a military dictatorship in Germany, and the military is making all sorts of policy decisions there. And in France, too, we see aspects of military overreach and extraordinary forms of justice. The military in France is able to do things during the war that the parliamentarians in Paris would never do. And even Britain has the Defense of the Realm Act that gives the civilian government a large amount of control. It’s not necessarily the military in Britain but the civilian government that is expanding its reach into people’s lives.

But these states conceived of themselves as nation-states, and so the idea that the military would, on behalf of the nation, exceed its authority and trump the rule of law, didn’t destroy the reason for being of the state. The reason for being of the French state is the French nation. A Rechtsstaat (constitutional state) governed by the rule of law wasn’t needed to function. Germany is the same way. But in Austria-Hungary, this was needed. Because Austria-Hungary depended so much on the law, the dynamic that is happening everywhere, where the military subverts constitutional rule, expands its authority into civilian life, and ignores laws and legal grounds, had a more detrimental effect. It affected the Habsburg Empire so much because it depended on those laws to begin with. Its reason for being in the modern era was constitutionalism and the rule of law. Because it was a state structured around the law, when the law was taken away in the time of war, it had a deleterious effect on the legitimacy of the state.

I’m curious about how you conducted your research for this project. Your paper is packed full of quotations from primary sources, detailed stories, and photographs. How did you go about finding all of this information?

We spent lots of time in military and government archives. Most of the things we cite in the paper are from Vienna, but we’ve also done research in Warsaw, for instance, and Slovenia. So when we write a book, it will have more local files and local things from Poland, Slovenia, Tyrol, the Adriatic coast, and maybe even Hungary too.

Were there any “aha!” moments in the research process?

One “aha!” moment I had came not from doing research but from renting a car and driving around battlefields, especially on the front between Italy and the Habsburg Empire. One of my friends who is from Slovenia showed me a military cemetery that was a few miles back from the front, near Caporetto (now Kobarid) in Slovenia. The Habsburg Empire created the military cemetery in, I believe, 1915 or 1916. On the crosses that mark the graves, there were little plaques that displayed the names of the deceased soldiers and their ranks. And as I was reading these plaques, I realized that Czechs were lined next to Germans, Poles, Italians, Hungarians, Slovenes, and Croatians. These people, from all of these different nations whose histories have divided since 1918, were lined side-by-side, together. They gave their lives for their empire. And their sacrifice has been almost forgotten. Their joint sacrifice, their multi-national sacrifice for a multi-national empire has been forgotten. And that was an “aha!” moment for me. When I went to graduate school, if you wanted to learn about the history of the Habsburg Empire and successor states, you had to read Hungarian history about Hungarians who lived in the Habsburg Empire. You had to read Slovakian history about Slovaks who lived in the Habsburg Empire. You had to read Austrian history about Austro-Germans who lived in the Empire. You had to read Czech history about Czechs in the Empire. People have taken the 20th and 21st century map of Europe and read it back into the past. And there was a moment when I was standing in that cemetery, surrounded by beautiful scenery, where I realized that there was something to writing a history of the whole, where you’re not just writing about Germans who lived in the Habsburg Empire, Hungarians who lived in the Habsburg Empire, Poles who lived in the Habsburg Empire, etc. There’s something to writing about the whole thing, the whole thing that was a common denominator for all of these people no matter what languages they spoke. So that’s what I’m trying to do—trying to recapture what was lost, forgotten, or erased.

Finally, what’s next? You mentioned that you’re working on a book on the Habsburg Empire?

Yes, we are hoping to turn the article into a book. The book will have a somewhat broader scope than the article. An overarching point of the book will be the internal conflict in the Habsburg Empire between the military and the rule of law, but we’re also going to have to talk about the international dimension of the Empire. When the British Empire and the French Empire decide they are going to destroy the Austrian Empire because it’s decrepit and not a nation-state, what is going on there? The British and the French are destroying an empire while hiding the fact that they themselves are empires too with their own problems. So, we want to address those issues as well.