Matt Kianpour ’24 is a science-computing major with minors in compassionate care in medicine, European studies, and poverty studies. Over spring break 2022, he received a research travel grant from the Nanovic Institute for European Studies to conduct research in Barcelona for his capstone essay. An aspiring primary care physician, Matt is undertaking a mixed-method study of public transportation and access to healthcare in European cities.

I love public transportation. Even in South Bend, a small midwestern city that could best be described as light on public transit, I have the Transpo schedule memorized. On campus, I am known for boarding my entire friend group on bus number seven for excursions to the mall, coffee shops, and Mexican restaurants. While public transportation is my hobby, my professional interests lie firmly in the realm of healthcare. My career goal is to become a primary care physician, one whose philosophy aligns with the World Health Organization’s definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

I believe we must view healthcare as a sociological institution. For me to be an excellent primary care physician, I need to be aware of the discriminatory social forces that prevent certain people, particularly those at the margins of society, from accessing responsive and quality healthcare. As a science-computing major, I am eager to apply quantitative analysis to qualitative issues, especially through the use of geographic information system (GIS) technology, which can be used to portray a community’s experiences, narratives, and in particular, challenges, in code and on maps. After many meetings with Anna Dolezal, student programs assistant director at the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, and Danielle Wood, associate director for research at the Center for Civic Innovation, I found a way to channel my passions for health care, transportation, and computational modeling into a research agenda.

My research considers how public transportation can facilitate or present a barrier to healthcare. Unfortunately, current scholarship highlights that in the U.S., “many public transportation routes do not provide access to medical care, especially for the most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods.”* Transportation can act as a roadblock to accessing healthcare facilities, resulting in missed visits and rescheduled appointments, delaying adequate care for patients.** These patients might include an undocumented factory worker unable to attend an appointment for her strained back or a low-income mother struggling to make it to her prenatal OBGYN visit. Volunteering at local family medicine practices in South Bend, I have witnessed how reduced access to transportation impedes access to healthcare.

Researchers have observed this connection between transportation and healthcare access across the U.S. My work aims to discover whether such barriers to healthcare exist in Barcelona, which, unlike cities in this country, has a universal healthcare system and a robust public transportation network. My research seeks to understand how well Barcelona’s public transportation system makes healthcare accessible for the city’s low socioeconomic status populations.

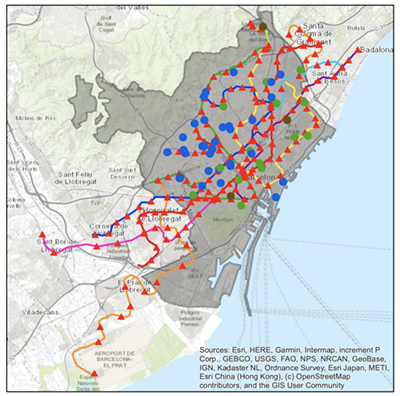

Prior to my field research in Spain, I spent the fall 2021 semester working closely with the Navari Family Center for Digital Scholarship, to complete a spatial analysis of Barcelona health care facilities, including primary care clinics, emergency centers, hospitals, and other clinics, using geographic information systems (GIS) software (see left). I created a model to identify healthcare facilities that are located within a low-income region, where the median annual household income is €17,500 (approximately $18,300) or less and which is within a walkable distance — 0.4 kilometers (0.25 miles) or less — from one of the Transports Metropolitans de Barcelona’s (TMB) 165 train stations. This model provided a sampling frame for choosing clinics for phase two of my project: ethnographic research conducted in Barcelona to understand whether physical access is a barrier to healthcare for the city’s lower-income residents. Thanks to a spring break research grant from the Nanovic Institute, I was able to travel to Spain to undertake this work.

When I arrived in Barcelona, I vowed to only travel by metro, no matter my destination. This gave me an opportunity to see and experience the full scope of the population served by the city’s main transit system as well as the excellent service available to them. I was perhaps a bit too enthusiastic to ride a GoA 4 UTO train, a fully automated and driverless train, which I had only ever seen online. From platform screen doors for increased safety on the platform to moving block communication-based train signaling, I experienced the cutting edge of modern transit technology. All of this is as readily available to locals making their way to a medical appointment as it is to tourists visiting attractions like the famously unfinished La Sagrada Familia basilica.

I rode the metro with school teachers, doctors, corporate workers, and even a group of FC Barcelona fútbol fans on their way to a match. I rode the train at 5 a.m. and took it home again at 5 p.m. after a day of visiting clinics, experiencing a train system that, with its modern technology and frequent service, certainly helps promote access to the city’s healthcare facilities. While I only spent a week on the rails, this experience revealed to me that the rail system is a microcosm of the community it serves with each train car a visible representation of the city’s population.

Over the week, I conducted semi-structured interviews with patients at clinics that met my sampling criteria and asked them about how transportation affected their access to healthcare. One encounter has stayed with me: a man in his 60s who had a transfemoral (above the knee) amputation to his left leg due to diabetes. We discussed his quality of life and pain management, and he explained that he uses a walker, which he feels gives him better mobility than a wheelchair. His wife and family are unable to provide transportation to his appointments, so he relies on the metro system. His visits to the clinic are vital: pain management is a constant challenge and his diabetes puts him at risk of developing diabetic neuropathy, a type of nerve damage that might require the amputation of his other leg. Because of the TMB's frequent service and disability-accessible trains and platforms, he can receive the care and monitoring he needs to protect his health and achieve a greater quality of life.

As an aspiring primary care physician, conversations like these excite me to build longitudinal relationships with my future patients. Conversations like these also underscore how, when we seek to enact change in our own communities, such as by improving public transportation services to provide greater access to healthcare, we should speak directly to the people those services would support. GIS is an important tool for understanding, though without conversation something may be lost in translation: that people are so much more than dots on a map. My plan now is to expand my research on the intersection of healthcare and public transportation to examine the same dynamics in London during the fall of 2022. These experiences and academic engagement with the evidence have been truly invaluable as I continue my work as an aspiring physician. I am grateful to the Nanovic Institute for its support.

Notes

*Center for Third World Organizing, People United for a Better Oakland, and Transportation and Land Use Coalition, Roadblocks to Health: Transportation Barriers to Healthy Communities (2002).

**Samina T. Syed et al, “Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access.” Journal of Community Health 38, no. 5 (2013): 976-93.

Originally published by at nanovicnavigator.nd.edu on August 18, 2022.