This summer, Sarah Nanjala, a Master of Global Affairs student in the Keough School of Global Affairs, received funding from the Nanovic Institute for European Studies to undertake advanced French language training in Brussels, Belgium. In this contribution to Nanovic Navigator, Sarah reflects on how her encounter with World War I commemoration in Ypres intersects with her graduate work in international peace studies. For another perspective on her trip, read Sarah's piece "Reparations for Colonialism" for the Keough Insider.

“This war, like the next war, is a war to end war.”

— David Lloyd George (British Prime Minister), c.1916

Almost 103 years after the end of the First World War, I visited the small town of Ypres (now Leper) in northern Belgium, the site of immense suffering during that conflict. Between 1914 and 1918, five major battles were fought in the Ypres Salient, an area that surrounds the main town. 300,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers died in the Salient. 90,000 of these fallen have no known grave. Now a bustling and vibrant tourist town, Ypres’ history casts a great shadow, demonstrating the lasting effects that war can have on a country and its people. As I walked down the streets of this historic town, I was struck by the resiliency of a human spirit that found the strength to rebuild itself after the chaos and destruction of total war.

In the summer of 2021, the world was beginning to emerge from the drastic lockdowns and restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. I was one of many students who seized the opportunity to travel for research and study for the first time in over a year. I traveled to Belgium to undertake advanced French language training, supported by a summer grant from the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. As a Master of Global Affairs student majoring in international peace studies, I was also able to use my time in Belgium to consider questions about post-conflict rebuilding and reconciliation in the European context and the part that collective memory plays in this process.

History—even when painful and difficult—should be remembered. This memory plays a crucial role not only in embracing our past and remembering those who we lost but also in creating a narrative that allows us to learn from the past and avoid repeating patterns of conflict. As Vincent Bernard, former editor of the International Review of the Red Cross has written: “understanding memory, not only individual memory but also collective memory, may be key to preventing future cycles of violence.”

In the case of remembering the First World War, these memories are now stored in the form of monuments, museums, and artifacts. The Menin Gate, for example, is a magnificent structure at the eastern exit of Ypres. It is one of four memorials in the area honoring British and Commonwealth soldiers killed during World War I. While several countries, including the UK, France, and other Commonwealth countries hold ceremonies on Remembrance Day, November 11, marking the end of the First World War, in Ypres, remembrance of those who died in the Great War is a daily ritual. Every evening at 8 p.m., a moving ceremony takes place under the arch of the Menin Gate where buglers from the local fire brigade play “The Last Post,” a traditional final salute to the fallen. This ceremony has been held without interruption since July 2, 1928, except for during the German occupation of the Second World War when it was conducted in Brookwood Military Cemetery, England. Each reverberating sound of the trumpets under the Menin Gate is a daily reminder of how crucial memory is in defining who we are as a people and that we should always strive to remember our collective past.

The big question then becomes: what and how should we remember? When it comes to conflict and post-war recovery, careful construction of historical narratives is vital because bad peace can entail more war (Frydenborg, 2018). It could be argued that the conclusion of the First World War, and the tensions and resentments that followed, helped birth the events that led to the Second World War. When the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919, many of its terms created resentment in Europe, particularly in Germany which had been forced to sign, take primary responsibility for the conflict, and pay for war damages, a significant burden as the country tried to recover and rebuild. Historians have explained the rise of Hitler and the Nazis in the 1930s as due, in part, to their exploitation of Germans’ sense of resentment and their creation of a narrative that cast Germany as the aggrieved party.

There is also significant debate over whether narratives and remembrance are an effective way to approach recovery and reconciliation, as opposed to allowing society to forget past grievances and traumas. Those in the latter camp argue that the highly subjective nature of memory means that it can easily be abused and manipulated to serve the interests of particular groups over others. Author David Rieff stands somewhere in the middle of this debate, writing that “one should strive for remembrance where possible but accept that there are times and places where more forgetting … is the only safe choice to make.”

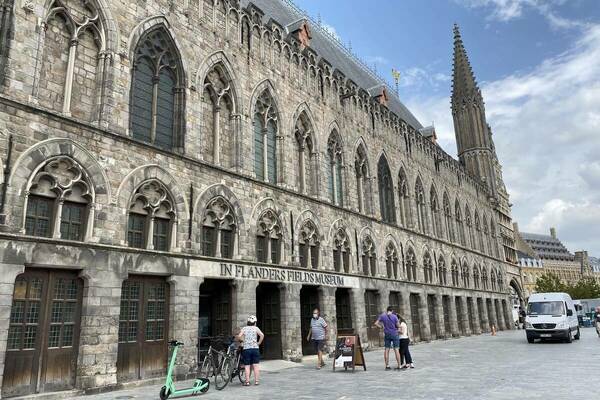

My visit to Ypres helped me see that in order to remember “objectively” we need to find the right narratives. In addition to the Menin Gate, I spent three hours at the In Flanders Field Museum, named after the poem by Canadian Lieutenant John McCrae in dedication to his friend, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, who died in the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915. Spoken from the point of view of the dead, the poem focuses on remembrance and individual sacrifices. Borrowing from this, the In Flanders Field Museum chooses to “share history” by preserving the memories of the war through remembrance. The museum does not set out to glorify war, but, rather, to suggest its futility.

While walking through the hallways and huge rooms, I noticed that most of the displays were of tools used in the war as opposed to the destruction itself. I interpreted the prevailing narrative as being a reflection on the futility of war. These tools included shell casings, war machines and guns, gas masks, medical equipment, army clothes, and, alongside these instruments of war, some replica tombstones of those who died. The museum included an interactive exhibit where the visitor can “speak” to a virtual survivor of the war and hear his personal story of loss, grief, and hope for an end to the war. These forms of memory representation created a narrative about the destructive impact of war on individuals, society, and countries, which, for me, demonstrated that conflict should be avoided at all costs.

The thousands of names on the walls of the Menin Gate, including those whose bodies were never recovered, impressed upon me that there must be better ways to resolve conflict. My five weeks in Belgium were a revelation, giving me new insights into the important role that peace ambassadors have in the world. As a peace studies student, I came to see firsthand the negative effects of conflict, both immediate and across generations. By the end of my trip, I had learned three important things: we must strive to remember history, narratives matter, and we should exhaust all avenues of diplomacy before the use of force. We owe it to the war dead and those who have witnessed the violence of war to remember and say “never again.”

Further Recommended Reading on the Subject

- Vincent Bernard, “Memory: A New Humanitarian Frontier,” International Review of the Red Cross 910 (April 2019), https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/editorial-memory-new-humanitarian-frontier.

- Brian Frydenborg, “The Urgent Lessons of World War 1,” The Modern War Institute, December 12, 2018, https://mwi.usma.edu/urgent-lessons-world-war/.

- “Our Story: Sharing History,” Flanders Fields Museum, accessed 1 October, 2021, https://www.inflandersfields.be/en/in-flanders-fields-museum-1.

- David Rieff, “Opinion note … and if there was also a duty to forget, how would we think about history then?” International Review of the Red Cross 901 (April 2019), https://international-review.icrc.org/articles/opinion-note-and-if-there-was-also-duty-forget-how-would-we-think-about-history-then.

About the Author

Sarah Nanjala is a Master of Global Affairs candidate and Kroc Institute Fellow ’22 in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. Her major is in international peace studies. A former print journalist for the Daily Nation, Kenya’s largest independent newspaper, Nanjala has written on a wide range of national issues including elections in violence-prone areas and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Originally published by at nanovicnavigator.nd.edu on October 04, 2021. Nanovic Navigator is a platform for stories told by students about their experiences exploring Europe and European studies through the support of the Nanovic Institute.