Fighting for Democracy and Human Rights Through the Arts

An Introduction

By: Clare Barloon ’24

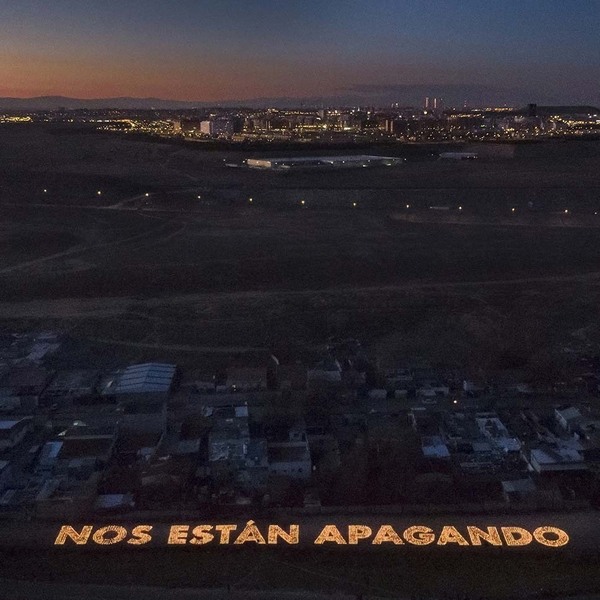

In a migrant settlement outside Madrid, 4,000 candles light up the night, calling for a restoration of energy in the settlement and recognition of the dignity of those displaced residents pushed into the shadows. In Greenland, on the banks of a glacial melt, artist Jessie Kleeman performs a complex dance with the snow-covered environment, mourning the lack of attention paid to Greenland’s post-colonial relationship to Denmark and the land’s position amongst rising sea levels and melting ice as the effects of climate change unfold. In Ukraine, Italian street artist TVBoy spreads a message of hope and optimism in light of the ongoing conflict. His murals position children, rendered in the iconic yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag, as daring artists for peace in their own right.

This exhibition by the Nanovic Institute, “Fighting for Democracy and Human Rights in Europe through the Arts,” brings into conversation many threads interweaving contemporary public and political issues in Europe. It follows last year’s exhibition dedicated to Ukrainian resistance in the face of the ongoing Russian invasion (titled “Ukrainian Art as Protest and Resilience”), at once revisiting Ukraine through the eyes of different artists while also expanding outwards to consider how artists throughout Europe frame and respond to issues of democracy and human rights.

The Nanovic Institute for European Studies, part of the Keough School of Global Affairs, and the students of the University of Notre Dame invite us to engage with some of the injustices most prevalent in our world today while highlighting stories of bravery, resistance, and humanity. This exhibition presents a series of works created by artists in Europe, accompanied by analytical insights provided by undergraduate students who conducted research during the 2024 spring semester. The exhibition showcases different formats, including performance, installation, street art, photography, illustration, and documentary film.

While the borders of what defines “Europe” are flexible and impermanent—reflecting how all forms of geopolitical identity are, to a certain extent, constructed and tenuous—all of the artists highlighted in this exhibition speak to those issues being grappled with by individuals and communities within and across Europe. Migration, conflict, authoritarianism, postcolonialism, housing, and human dignity emerge as central concerns in the minds of these artist-activists.

In some ways, these artists uncover hauntings—ghosts of war, colonial injustice, and the dangerous paths of migration—returning in spectral form. Polish musician and poet Grzegorz Kwiatkowski, who spoke to students as part of this project, uses his poetry to dig up the ghostly remains of the Holocaust in Poland. His poetry offers a cacophony of voices that bear witness to brutality and challenges “society’s preference for silence in the face of history’s terrors.” William Faulkner’s famous dictum, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” rings true here as the tragedies and injustices present in Europe’s history, both at home and abroad, recur in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, in the continued marginalization of the former victims of European colonialism, and in the ways migration, spurred by climate change, lack of economic opportunity, and violence, is demonized and ignored, leading, for example, to the deaths of thousands in the Mediterranean.

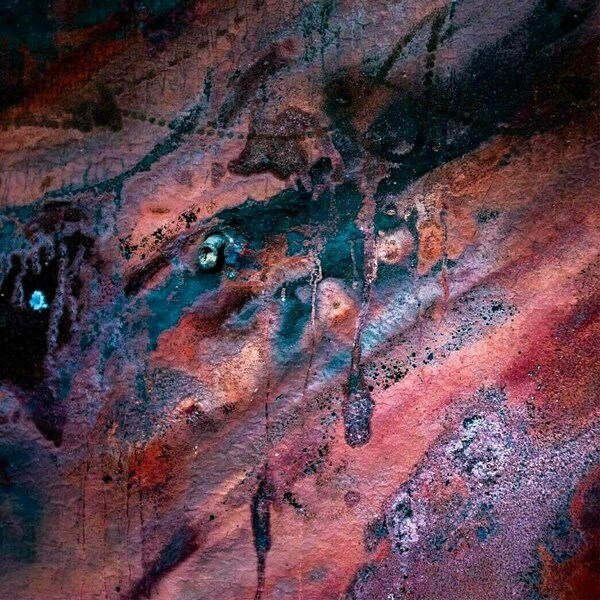

The pieces in this exhibit conjure up the specter of these tragedies, each eliciting their distinctive echoes in contemporary European societies. Iva Sidash’s “The Wall: Witness to the War in Ukraine” presents intimate “portraits” of damaged and destroyed walls in Ukrainian homes. The scarred and scorched walls form a new language of absence and mourning for those killed in the invasion and displaced from their homes, uncertain when or if they will ever return. Binta Diaw speaks to the ongoing exploitation, dehumanization, and marginalization of Black Italians in “Negro Sangue,” a ghostly and disquieting installation work. In celebrated Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei’s “Law of the Journey,” Ai depicts faceless migrants crowded onto a raft and suspended in midair, the black rubber vessel and occupants looming hauntingly over the installation space.

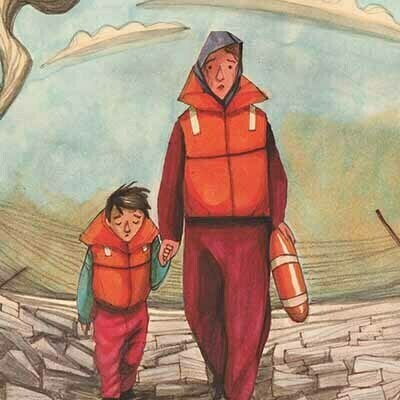

The issue of migration has undoubtedly become a flashpoint in recent years as politicians and news sources have cast migrants as dangerous invaders or helpless victims. These artists respond to issues of migration and displacement with empathy, attempting to humanize the “faceless masses” satirized in Ai’s work. Images of refugees and migrants crossing or attempting to cross the Mediterranean have been especially prevalent as overloaded and unsafe boats continuously capsize. For this reason, many artists commenting on migration feature eye-catching images like the bright orange life-jacket or overcrowded dinghies as symbols of the ongoing crisis. Diala Brisly, herself a Syrian refugee, juxtaposes danger with messages of hope in her “Life Jacket” series and shines a light on the prevalence of gender-based violence and abuse in the refugee experience. Jean-Marc Joseph, a documentarian, depicts the inhumane and potentially deadly conditions many migrants endure when attempting to reach Europe in his documentary “Europe’s Forgotten Graveyard.” Mahn Kloix’s large public murals depict moments of empathy and human connection as a child is pulled out of a raft or a migrant couple embraces. These works call for a human-centered response to an issue often reduced to nameless and faceless statistics.

Medium, as well as message, fundamentally shapes a work of art. Many artist-activists naturally turn to public murals, which explicitly call for recognition and awareness on the part of the public. Asbestos, an Irish street artist, forces passersby to contend with the housing crisis and homelessness, topics heavy with social stigma, in his mural “What is Home?” The mural’s depiction of an anonymous person who has covered their face with a cardboard ‘house’ is vivid and striking, literally and figuratively larger than life.

On the other hand, a medium like photography is often associated with journalism and depictions of reality. Pasha Kritchko’s documentary-style photos of political turmoil in Belarus feel gritty and grounded. In his photography, authoritarianism seems palpably present, looming heavily over Belarus, where political repression and exile have harmed democracy and torn apart families. At the same time, the determination of peaceful protestors persists, offering a message of hope for the restoration of democracy and rights. Like Sidash, Kritchko’s photography was transformed by political violence and rising authoritarianism in Eastern Europe. Kritchko, a wedding photographer, wielded his camera as a weapon of documentation in the midst of the 2020 protests to tell the story of Belarusians’ protest and their suppression.

The European Union’s 2017 report “Exploring the connections between arts and human rights” highlights the interdependencies between human rights and the arts, while remaining aware of how the arts can push dishonest or hateful messages. The report argues for the importance of the arts to chronicle and protest human rights abuses, appeal to governments and policymakers, and “heal the wounds” of violence. The report serves as a reflection on the importance of sustaining and protecting the arts in service of human dignity. Another source of inspiration was the Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) report “Art Is Power: 20 Artists on How They Fight for Justice and Inspire Change,” which spotlights artists who employ their talents in service of social and political movements. The ARC project fights for artistic freedom as itself a human right. In describing its mission, the ARC writes: “Freedom of artistic expression is a fundamental human right and an indicator of a healthy and free society. But artistic freedom is under assault: autocratic regimes fear artists because they express cultural identity, advance new ideas, promote dialogue, and bear witness to inhumanity.”

Inspired by these and many other sources, this exhibition asks, “How do artists respond to issues of human rights and democracy?”

-

How can the arts generate an awareness about the injustices that persist in our world?

-

How can the arts be a force for good and a call to action?

-

How can the arts, in particular ways, invite discussions about colonialism, authoritarianism, warfare, displacement, and other obstacles to belonging that continue to haunt the lives of people around the globe?

This exhibition invites you to reflect on these central questions through the individual visions of the 11 artists it features.

Migration

What is the human experience of crossing borders? How do we ensure human rights hold strong, and what is the role of democracy in migration?

Law of the Journey & Europe’s Forgotten Graveyard

Art by Ai Weiwei, documentary by Jean-Marc Joseph, research by Monay Licata

Fragments de Voyages

Art by Mahn Kloix, research by Ethan Chiang

Life Jacket

Art by Diala Brisly, research by Anna Gazewood

The Battle for Democracy

How do we ensure the ongoing strength of democracy and human rights when they are challenged by autocracy? What about aggressive imperialism? What can the arts say in response?

The Wall: Witness to the War in Ukraine

Photography by Iva Sidash, research by Cate Porter

Belarus 2020 and Belarusian Connections

Photography by Pasha Krtichko, research by Annie Rehill

Street Art in Ukraine

Art by TVBoy, research by Isabelle Wilson

Displacement

How can the arts highlight the need for justice when displacement, homelessness, and under-resourcing occur across the world?

Nos están apagando

Art by Boa Mistura, research by Abby O'Connor

What Is Home?

Art by Asbestos, research by Jane Palmer

Decolonization

How can art help democracies grapple with the legacies of colonialism and embrace a reimagined future?

Arkhticós Doloros

Art by Jessie Kleemann, research by Erin Tutaj

Nero Sangue

Art by Binta Diaw, research by Kendra Lyimo

Clare Barloon is a senior from Bethesda, Maryland, majoring in art history and global affairs with an international peace studies concentration and a minor in French. She currently works as a research assistant for a professor at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and as a strategy tutor for student-athletes. Her senior year has been dedicated to completing a thesis in art history titled “The Formless Form: Figuring Ecology and Slow Violence in the Art of Minia Biabiany and Cecilia Vicuña,” which examines the “eco-aesthetics” these contemporary artists employ to address the harms of ecological destruction and postcoloniality. She is excited to be working on her second Nanovic project.

Project Background

By: Abigail Lewis

In January 2023, the Nanovic Institute launched its first public-facing undergraduate research project and exhibition on Ukrainian artists fighting against invasion, cultural annihilation, and anti-democratic forces through their art. We followed this project with a second installment, “Writing the War in Ukraine,” which was the culmination of group research on poetry conducted by students at the Ukrainian Catholic University and Notre Dame.

This project, “Fighting for Democracy and Human Rights through the Arts,” the third installment in this series, expands on our earlier research by placing the work of contemporary artists on human rights issues in a larger frame. Our goal was to contextualize artists’ critical role in raising awareness of human rights issues. The project represents various media that reflect different ways in which artists can engage in public discourse about human rights and democracy. This exhibition includes documentary media such as photography and documentary film, which engage politically by documenting human experiences and the physical destruction of cities and landscapes. It includes conceptual, installation, and street art, all of which media bring political messages into public spaces, forcing visitors and passersby to reflect on messages about warfare, migration, and displacement. Some of these public works, such as the murals by TVboy in Ukraine, are intended to inspire hope and strength. Finally, the exhibition includes artistic reflections on personal experiences by the artists themselves.

Conversations with politically engaged artists, including Grzegorz Kwiatkowski and Iva Sidash influenced the project’s themes and outcomes. Kwiatkowski, a musician and poet from Poland, shared his experiences with students and discussed the power of public art as a platform for discussing human rights abuses and memory politics. Kwiatkowski, once a supporter of the idea of keeping politics out of the arts, began using his art as a platform for political engagement after the murder of the mayor of Gdansk. He dedicated his set at South by Southwest to the memory of the mayor. For him, this moment was like opening a new door. Kwiatkowski also discussed his poetry, which viscerally unearths the voices of the Holocaust in Poland. Through his art, his goal is to break the silence in Poland about the Holocaust–especially Polish collaboration. Sidash, a photojournalist and photographer from Ukraine, discussed her experiences photographing the war in her homeland with students, highlighting the stories of the people she photographed. She explained that war transformed her work as a photographer–she was compelled to photograph what was happening and the people she encountered, many of whom had lost everything. She challenged students to consider how war impacts the artistic endeavor—something we typically associate with beauty and aesthetics. Photography is one way that she seeks to amplify war stories and spark conversations about warfare and its impact.

A recurring theme that emerged throughout the project was ghosts and haunting. Europe’s past–the legacies of colonialism, warfare, authoritarianism, racism, and labor exploitation–all palpably haunt the present realities of these artists. The theme of haunting emphasizes the interconnectedness of the past and present, the reality that the specters of past violence continue to influence current inequities. Sidash’s “Further Along the Road” series pictures this intermixing of past and present. The photographs, made on expired film, follow her path on the road to Crimea, a path that she often took as a child on the road to family vacations. Here, the tension between the past and present collide–a memory of childhood joy interrupted by the reality of war. This example–and others featured here in the exhibition–show how the arts are a medium and platform for representing the past honestly, promoting dialogue about the challenges of the present, and advocating for a better future.

Introduction by Clare Barloon.

Project leadership by Clare Barloon and Abigail Lewis.

Online exhibition produced by Keith Sayer.

Project funding and direction provided by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, part of the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame.

Special thanks to Jake Kildoo, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski, and Iva Sidash.

Header image: From the exhibit "Further Along the Road" by Iva Sidash, photograph on film, 2022. Image used with permission from Iva Sidash.