Maire Brennan ’25 is an accountancy major studying at the Mendoza College of Business. During March 2024, she traveled to Copenhagen, Denmark with assistance from the Nanovic Institute for European Studies and the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts (ISLA). The focus of this trip was a deep dive into the principles of Danish design and how they relate to core elements of Catholic Social Teaching.

From March 8-15, 2024, I conducted research in Copenhagen, Denmark, to investigate how Danish design, with its emphasis on simplicity and sustainability, not only aligns with but promotes the principles of Catholic Social Teaching to create products, systems, and urban communities that contribute to the common good and enhance human flourishing. The research methodology primarily consisted of ethnographic fieldwork and museum visits. Throughout the trip, I was able to visit four of Denmark’s prestigious art and design museums: Design Museum Denmark, The Danish Architecture Center, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, and Ordrupgaard. The research provided an opportunity to integrate my interest in design and the common good with my business education, ultimately seeking opportunities to use design and Catholic Social Teaching principles to positively contribute to society.

The key questions that guided my research were:

-

How do Danish design principles reflect and contribute to the cultural values of promoting the common good and human flourishing?

-

In what ways does Danish design address the needs of diverse communities and contribute to inclusivity?

-

In what ways does Danish design address the growing environmental challenges and contribute to sustainability?

-

-

How can the lessons learned from Danish design be applied to global design practices for the betterment of society?

The research provided insights into how Danish architecture, infrastructure, urban planning, and interior design reflect and contribute to CST. I identified three primary CST themes that I observed most frequently in Danish design: care for Creation, the common good, and human dignity.

Care of Creation

Denmark’s commitment to sustainability was evident throughout my research. At the Danish Architecture Center, I learned about the innovative building methods Danish architects are employing to create sustainable structures that use less energy, produce less carbon emissions, and can be deconstructed and rebuilt.

Danish builders can accomplish these feats by using concrete alternatives like wood, and seagrass, and prioritizing adaptive reuse I discovered a surprisingly similar approach being taken in textile and fashion design at Design Museum Denmark. Here, I observed how sustainable fashion does not just require responsible materials and manufacturing but a commitment to caring for clothes in a way that increases their longevity by promoting adaptive use.

Through my participatory observation, I experienced how sustainability is ingrained in the design of the city, demonstrated through the widespread cycling culture and supporting infrastructure, efficient and accessible public transportation, and use of alternative energy sources like wind power.

Human dignity

I was struck by the inclusive nature of Danish design, which in turn promotes human dignity by making spaces accessible. As I navigated the city, one of the first things I noticed was that there were elevators available at nearly every staircase. Even at relatively small staircases in museums and at train station entrances, there were electronic lifts that could be used for wheelchairs, strollers, bikes, and other accessibility needs.

There were also ramps built into staircases in many areas. Since bikes are common, I saw many cyclists utilizing these ramps as well as moms with strollers and elderly individuals with walkers. This demonstrates how designing inclusively can provide affordances for many different needs beyond those for which they were initially designed. Additionally, I observed how the metro cars provided affordances for those traveling with bikes and strollers. At Design Museum Denmark, I saw inclusive product design in their cup exhibit. Overall, I was impressed by the care and consideration of design for those with different needs.

The common good

Danish design promotes the common good by prioritizing work-life balance and leisure for its citizens. This culture emphasizes creating functional, comfortable, and aesthetically pleasing work environments that support productivity and well-being.

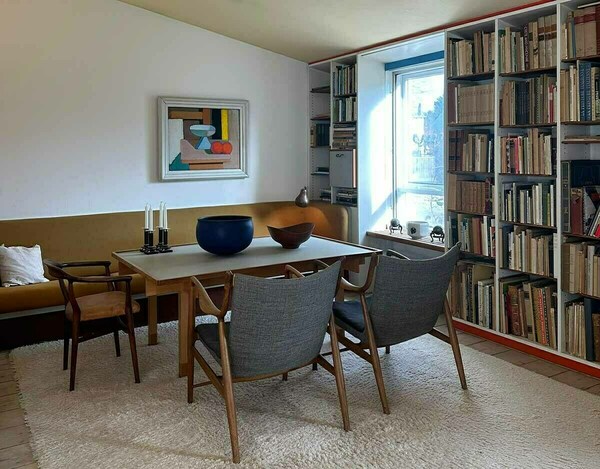

At Finn Juhl’s House at Ordrupgaard, I saw these principles in practice in his home and workspace. Using simplistic furniture, warm wood, and inviting colors, Juhl created a space that supports both work and leisure. Additionally, Danish design extends beyond the workplace to leisure spaces, such as parks, public areas, and recreational facilities, which are often designed to encourage social interaction, physical activity, and relaxation.

At the Danish Architecture Center, I studied Denmark’s history of designing recreational spaces and parks to promote leisure. A great example of design for leisure is CopenHill, a waste-to-energy power plant with a ski slope on its roof. By providing well-designed spaces for both work and leisure, Danish design enhances the overall quality of life for citizens, promoting a sense of community, well-being, and fulfillment.

Day-to-day experience

From unlocked bikes lining the walls of buildings to mailbox signs listing the residing family members in each home, it was evident that the city’s inhabitants wholeheartedly trusted their fellow citizens.

In some ways, my experience living in Copenhagen for a week was exactly what I had expected. From my preliminary research, I expected reliable and efficient public transportation and the Metro did not disappoint. For example, I was able to make it from my hotel to my gate at the airport in under twenty minutes, which starkly contrasted with my three-hour journey to O’Hare Airport in Chicago. Similarly, the cycling culture lived up to the many articles I read before my trip (whatever you do, do not step into a bike lane, especially during peak commuting hours). I anticipated walkable streets and public parks and sure enough, they were filled with people enjoying the outdoors despite the harsh March wind and gloomy skies.

In other ways, I was surprised by the experience. Naively, in focusing my grant research on design anthropology, Danish design, and CST, I neglected to thoroughly research the country’s cultural values before visiting. This was somewhat intentional in the sense that I wanted to immerse myself in the lifestyle and discover these values through my interaction with design. For example, I was unaware of how trusting Danes are. From unlocked bikes lining the walls of buildings to mailbox signs listing the residing family members in each home, it was evident that the city’s inhabitants wholeheartedly trusted their fellow citizens. A local woman I met told me that she had walked home from the city center to her house nearly four miles away on numerous occasions—at night.

My days would begin with me waking up in my studio hotel room and getting dressed for the day. For March, it was chilly, accompanied by strong winds, so I dressed accordingly. I would then stop for breakfast at the small restaurant in the lobby of the hotel before making the short walk to the Amager Metro station. They had typical Danish breakfast foods like rye bread, soft cheeses, and meats, as well as fruits and pastries. Depending on where I was going for the day, I would usually visit a museum first.

Due to their exceptional train system, I had no issues getting to any of my research locations. Along the way, I would observe the people and spaces around me. For this reason, many of my pictures are taken of train stations and walking paths. Their transportation systems exemplified their commitment to sustainability and accessibility. Once I was at the site, I would spend a few hours exploring the museum and taking pictures when appropriate. Then, I would typically head back to the city, and visit a new area based on my preliminary research or on recommendation from locals. For example, one afternoon I explored Norrebro, a multicultural neighborhood with a vibrant immigrant population that is popular with the younger population. Here, I visited Superkilen, a popular design park, and local shops with Danish brands. Next, I would look for a coffee shop to read and journal about my day. Eventually, I would make my way back to a Metro station and head back to Amager as it got dark. Usually, I would walk over 20,000 steps and at least 8 miles a day. Once I was back at the hotel, I would make pasta at my kitchenette and go to bed.

The funding from the Nanovic Institute and ISLA enabled me to conduct in-depth research in Copenhagen, covering travel expenses and museum fees. Due to the ethnographic nature of the research, this funding was crucial, as it allowed me to engage directly with the Danish design community and environment, which would not have been possible otherwise. I presented this research for my final project in Design Anthropology, and it will go on to serve as a foundation for my senior thesis, as I draw on the insights and experiences gained from this exploratory study to develop my research question.

Originally published by at nanovicnavigator.nd.edu on June 13, 2024.