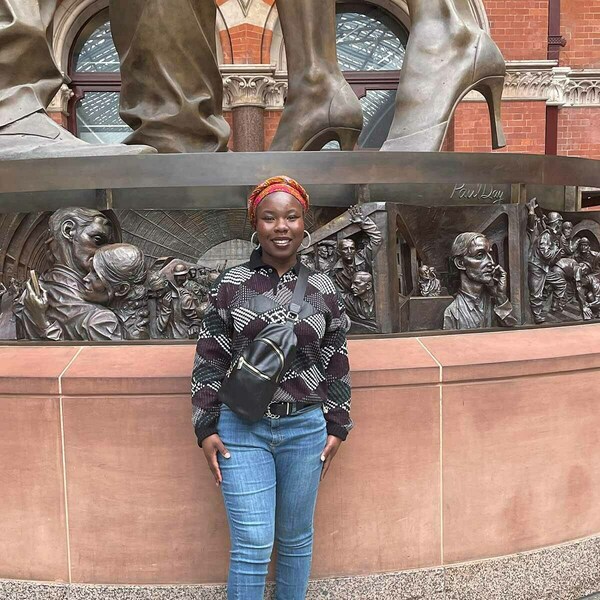

Ida Addo ’24 is an economics major with a minor in the Hesburgh Program in Public Service. In March 2023, she spent one week in London, supported by a Nanovic Institute for European Studies spring break research grant, conducting research for her capstone project. Her project, titled “London Urbanscape and Policies: Their Effect on the Economic State of the Windrush Generation,” builds on her interest in examining the welfare of marginalized groups across the world and the characteristics of the barriers they face. In London, she conducted research on the policies and urbanscapes that have contributed to the hindrance of economic progress among Afro-Caribbeans in the UK.

We have all met that kid, the one whose nosiness and curiosity about their neighbors and community residents calls for an automatic eye roll. With such kids, every drive or casual stroll provokes chatter, as they pester you with questions from “Oh mom, why does their house look like that?” to “Why are the people who live there different from those that live here?” or “I don’t see her grandmother anymore, where did she go?”

The temptation to silence this kid rises with each question. But hear me out! What if I told you that their observations are not pointless?

I became that kid.

Is it not important that we challenge what has become normalized so we may overthrow the institutions that continue to marginalize certain people more than others? I became that kid when I discovered that accessibility, context, and economic mobility lay at the heart of human rights and the recognition of human dignity.

“Why are the people who live there different from those that live here?”

The article “Can You Move to Opportunity? Evidence from the Great Migration” (American Economic Review, February 2022), by the American economist Ellora Derenoncourt, sparked my curiosity to explore the effects of migration and neighborhoods on intergenerational socioeconomic mobility. As I studied the intricate link between poverty and access to housing, employment, and education, I had the urge to challenge the normal. After reading Derenoncourt’s article, my next question was “What are the parallels between the Great Migration and the Windrush generation?” I wanted to understand the similarities and differences between the experiences of the approximately six million African Americans who migrated north from the American South in the middle decades of the 20th century and those of Afro-Caribbean migrants to the UK during a similar era.

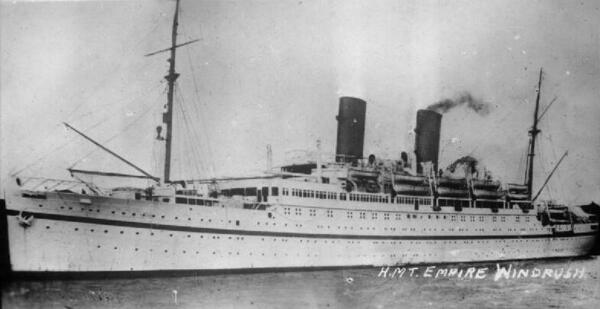

My research follows the seismic demographic change from 1948 to 1971 with the entry of Afro-Caribbeans to London and its key policy responses. I took the unsettling observations of the immigrant experience that I wrestled with a step further and turned them into research questions to understand the impact of the London urbanscape and its policies on the economic state of the Windrush generation and their descendants.

Derenoncourt drew some connections between place and the economic earnings of Black migrants that moved to northern American cities from the South during the Great Migration. I particularly focused on housing and employment as critical economic factors that reveal hindrances to the successful economic development of the Black British population at large. As I walked the alleyways of Hackney, the graffiti on the walls, the positioning of Brutalist social housing structures, and historic pictures of bombed-out homes that early West Indies immigrants occupied animated the plights of the Windrush generation. There, my questions like “Who owns this house?” and “Did their grandparents live here too?” were not so odd. The multiplex answers to these questions do not solely tell an economic tale. They reveal pernicious colonial legacies and unfairness in the British rule of law, adding layers of complexity to the lives of these immigrants.

The dawn of the Windrush generation in the mid-20th century

From the 1940s through the ’60s, Britain endorsed open borders to allow Commonwealth citizens from the West Indies to fill the employment gap after World War II. These immigrants were invited to fill labor requirements in London's hospitals, transportation venues, and railway development. This arrangement conferred British citizenship and the right to settle in the UK to all people from the British colonies to help rebuild the country. The newly arrived Caribbean workers were subjected to low-quality housing in areas like Brixton, Hackney, where they first settled. Afro-Caribbean immigrants in the ’50s could not purchase homes due to sale ads that read, “No Blacks, No Dogs, and No Irish.” They were either charged twice the market rent price by ruthless private landlords or subjected to deteriorating conditions in council estates. In the ’60s, the persistence of Black activists, who refused to be silenced, led to investigations into the Hackney Local Housing Authority, which proved the agency’s policies were discriminatory towards Black residents. Homeownership is a vital tool for wealth building, one from which Black Brits have been systemically excluded.

Exclusion from housing opportunities in earlier generations has led the median accumulation of wealth through homeownership in Black families over the past decade in Great Britain to be zero, a stark contrast to a net £115,000 for White British property owners. The sentiment towards the Windrush generation turned hostile as Britain grappled with its colonial legacies. Despite their contributions to British society, this hostility was reflected in the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act which restricted the entry of Commonwealth citizens into the UK for work.

The Windrush scandal and 21st-century outcomes

The plight of the Windrush generation was revisited in British national discourse after the Windrush scandal emerged in 2017. Hundreds of Commonwealth citizens from this group had been wrongly detained, deported, and denied legal rights. Falsely considered “illegal immigrants” or “undocumented migrants,” they began to lose their access to housing, healthcare, bank accounts, and driving licenses.

The compounded impact of historical discrimination and policy failures exemplified in the Windrush scandal resulted in the persistence of intergenerational poverty. The economic state of Afro-Caribbean immigrants bears witness to this phenomenon. Their decline in economic well-being is evident, as for every £1 of white British wealth, Indian households have 90-95p; meanwhile, Black Caribbean households hold around 20p. This gap reflects the ramifications of the British Empire’s colonial legacies and policy failures toward a group that contributes tremendously to the British economy.

On the other hand, the bustling of the markets, the rhythm of the jazz restaurants, and a plethora of businesses tell a tale of the hopes that Afro-Caribbean settlers had. British citizens with Afro-Caribbean heritage continue to be leading figures in Britain’s public domain. Diane Abbott, the first Black woman to be elected to parliament, and Bernie Grant, who also served as an MP, are prominent examples of the resilience of the descendants of the Windrush generation.

Nonetheless, we cannot fail to acknowledge the inequities that persist today. The intergenerational drag hypothesis views contemporary disparities as the cumulative effects of macro-level systems interacting with one another in ways that generate and sustain racial inequalities.

The economic well-being of Afro-Caribbeans from the mid-20th century through contemporary times has always been stunted in part due to wage inequality. The 1944 Education Act wrongfully labeled Afro-Caribbean children as “educationally subnormal,” indicating a supposed limited intellectual capacity. This incorrect label affected their access to quality schools and educational achievement, which led to diminished employment opportunities.

Research applications and conclusions

By gaining a greater historical understanding of the structures that have constrained Black mobility in the UK, I have started to consider comparisons with similar policies in the US, such as redlining, a discriminatory practice that limited Black homeownership.

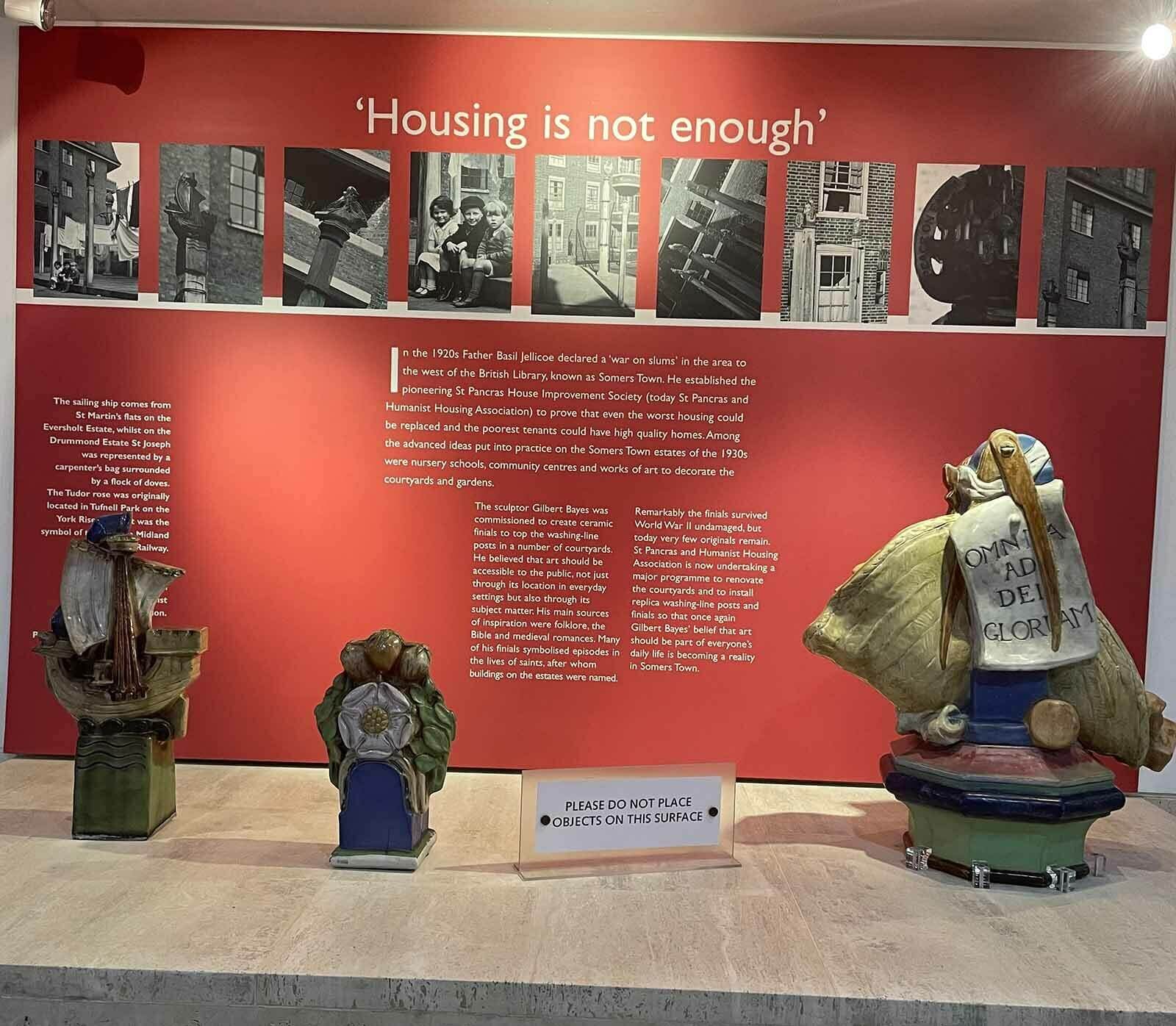

The residency of Afro-Caribbean migrants in the UK has been subject to instability, both historically and in recent years. The Hostile Environment legislation empowered the Home Office to wrongfully detain and deport many immigrants from the Windrush era. Without the necessary documents to prove their right to remain, many legal citizens of Afro-Caribbean descent from that period were inaccurately labeled “illegal immigrants.” This instability impacted subsequent generations of Black British folks descended from those migrants. The dispersal of communities, loss of employment, and lack of housing regressed the economic mobility of their progeny. Memoirs and collections from the Black Cultural Archives and the British Library disclose the gradual erosion of the social and economic rights of victims and their families during periods of inhumane treatment.

When your sources are derived only through a computer screen, the narrative uncovered by your research can be one-dimensional. Living out the research bridges the gap that exists where data has not caught up with the lived experiences of the people.

Every day, I lived my research by experiencing the city of London. The borough markets, ethnic enclaves, and interactions with Londoners who elaborated on their experiences gave me the language to express the outcomes of my research. My research focused on two key indicators of economic progress that are also foundational elements to the urban core: housing (homeownership) and employment. Observing the city provided a comprehensive view of the environment that allowed for the institutionalization of particular policies and the quality of life of contemporary immigrants. I also witnessed firsthand the engagement of local governments in the economic outcomes of Commonwealth citizens and their progeny.

My experience doing research in London helped me understand the importance of housing accessibility, the types of amenities that should be available in a neighborhood, and the policies that coalesce to determine the economic well-being of marginalized groups.

In addition, my time in London has taught me not to silence the nosy kid within that prompted me to ask difficult questions. To engage in successful research with this caliber of question is to view the city as a living and breathing being. When your sources are derived only through a computer screen, the narrative uncovered by your research can be one-dimensional. Living out the research bridges the gap that exists where data has not caught up with the lived experiences of the people.

Originally published by at nanovicnavigator.nd.edu on June 22, 2023.