Like many of its European neighbors, Denmark has a long history as a colonizing nation. The Nordic nation participated in the trans-Atlantic slave trade for over two hundred years, with slave colonies in what is now the American Virgin Islands, colonial trade-ports on the East coast of India, and a slave fort in contemporary Ghana. The Greenlandic Inuit have been under Danish rule for multiple centuries. Yet, colonial amnesia is strong in the Nordic countries, as is the belief that they were mere bystanders to European colonialism and slavery and therefore do not have a racialized view of the world. This notion that Nordic countries are free from race-based thinking is a fallacy. One consequence of ignoring race in this way is an unquestioned conception of Whiteness.

Scholars of race have referred to this self-perceived bystander status as Nordic Exceptionalism: deliberately (and conveniently) ignoring select parts of Nordic history and professing to have built an egalitarian democracy that is color-blind and plays no role in a racialized global power hierarchy. Nordic Exceptionalism is an ideology that makes it almost impossible to discuss Whiteness, race, and racism in Denmark. But, race matters because when Danes refuse to question racial differences and the privileges of Whiteness, they also fail to question a dominant narrative in which Danish national identity is White. This reinforces rather than challenges the hegemony of White racial privilege. Nordic Exceptionalism also renders race and racism as foreign, even though race and colonialism are foundational to the development of modern European states, including Denmark. The construction of a European or Danish identity is a relational process. There is no European identity without the non-European, and there is no “Western” without the “non-Western.” Europeans became Europeans and became White by defining “the other” through “conquests,” imperialism, and colonialism.

Multiracial ethnic-Danes are questioned about where they are “really” from, assumed to be foreign and spoken to in English, and subjected to sexual exotification, stereotypical assumptions about their Brown bodies, racist jokes, and verbal racist abuse.

Like other mainland European countries, the Danish government defines an ethnic-Dane based on jus sanguinis (law of descent), that is, a person who has at least one parent who is both a Danish citizen and born in Denmark. My research investigates the lived realities of multiracial Danes with one immigrant parent. These individuals are officially ethnic-Danes, have multigenerational Danish heritage, are fully versed in cultural expressions of Danishness, and are indistinguishable from White ethnic-Danes except for their skin color. Interviews with these individuals show that multiracial ethnic-Danes are racialized as foreign in social interactions, and their claims to Danishness are challenged by White ethnic-Danes daily. Multiracial ethnic-Danes are questioned about where they are “really” from, assumed to be foreign and spoken to in English, and subjected to sexual exotification, stereotypical assumptions about their Brown bodies, racist jokes, and verbal racist abuse. These lived experiences are empirical evidence that Denmark is not race-neutral. While rejecting racial categorizations is common across mainland Europe, the Danish government and many Danes simply replace an absent racial vocabulary with words such as ethnic, foreign, and immigrant. It is, therefore, easy to claim that society is free from racial discrimination, even though that society still employs a racialized ethnicity framework that conveys a non-White category, otherness, and, as such, racial difference.

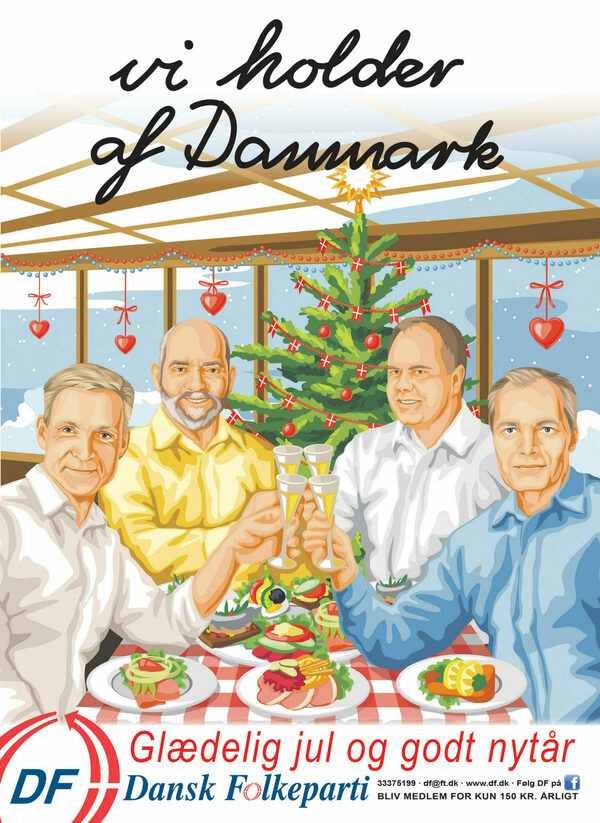

The Danish government frames non-Western immigrants and multiculturalism as a threat to the “social wages” that Danes enjoy, justifying differential access to socio-economic and political benefits and privileges. Multiracial ethnic-Danes also report feeling alienated from a common collective due to the negative public discourse about non-Western immigrants. The Danish mainstream media and public discourse on immigration suggest that non-Western immigrants and their descendants are significantly different from ethnic-Danes. Populist rhetoric frames immigrant descendants as costly for the welfare system, unwilling to integrate, and a threat to the integrity of the ethnic-Danish identity. Politicians, in particular, are guilty of framing national identity around Whiteness and a multigenerational Danish heritage. For example, the political platforms of The Danish Peoples’ Party and the New Right explicitly link immigration from non-Western countries with threats to Danish culture. Their campaign posters depict White people around a traditional smorgasbord to represent “Danishness” and pictures of Brown youths in hoodies as threats to this Danishness. Political figures on the left, including the Social Democrats, are also guilty of framing non-Western immigrants as a threat to a cohesive culture and national identity. However, a recent study shows that the majority of non-Western descendants are socio-economically indistinguishable from ethnic-Danes. Most Danes, irrespective of parental origins, have similar levels of educational achievement and access to employment, pay an equivalent amount of taxes, and contribute equally to the welfare system.

Immigration to Europe is primarily a consequence of European colonialism and the unequal global economy that resulted from centuries of exploitation. The Danish government detaches current geopolitics from European colonial history and fails to recognize that current migration patterns result from the legacy of colonialism. In 2002, the government started a highly racialized practice of placing immigrants into Western or non-Western categories. This reflects a contentious immigration debate begun during the 2001 election and a subsequent political shift due to the Danish People’s Party’s election gains. The Western category includes European countries and their former settler colonies, while all other countries fall under the non-Western category. Within this schema, “Western” denotes predominantly White countries and reflects a hierarchy based on a White cultural hegemony divorced from seemingly “neutral” geographical categories. Despite its location in the Western Hemisphere, South America falls under the non-Western category. These categories reflect an assumption about historical, socio-political, and cultural (in)compatibility with Danish society that maps directly onto race (White and non-White).

The use of “Western” and “non-Western,” in the context of immigration law, is a linguistic strategy to cover up racist and discriminatory language as a way to avoid directly saying something racially offensive. In so doing, the Danish government assigns racialized characteristics to immigrants based on their place of origin, giving a common-sense justification to “naturalize” differences between groups with different skin colors. From there, the Danish government frames non-Western immigrants and multiculturalism as a threat to the “social wages” that Danes enjoy, justifying differential access to socio-economic and political benefits and privileges. For example, Denmark, which has the most restrictive immigration laws in Europe, recently implemented a series of public housing policies that explicitly discriminate based on non-Western ethnicity. Despite decades of immigration and integration policy that specifically and expressly disadvantage groups that are non-White, politicians and the general public overwhelmingly deny that race matters in Danish politics and civil society. But let’s state the obvious: Danish politicians see race, White ethnic-Danes see race, and minority racialized Danes see race.

Legal citizenship or immigration status does not, in practice, define the boundary around who is or isn’t Danish. In everyday interactions, it is racial phenotype and skin color that determine access to cultural citizenship and belonging.

Racially motivated hate crimes are the most direct evidence of how race matters in Denmark because racism and race are physical realities that cannot be ignored. Registered hate crimes have increased significantly over the past three years, most commonly in the form of public harassment. Moreover, immigrants and descendants report experiencing hate crimes twice as often as ethnic-Danes. A recent analysis of national politicians’ Facebook profiles shows that the leader of the Independent Greens, Sikandar Siddique, whose parents are immigrants from Pakistan, receives more racist abuse and personal threats than any of his political colleagues. The study also found that the Danish People’s Party social media accounts facilitate hate speech because their posts receive the most racist and xenophobic comments about non-White individuals, immigrants, and Muslims.

Instances of public harassment are easy to identify as racially motivated macro aggressions. But, racialization processes, that have significant psychological effects, also occur in more subtle ways and in everyday mundane interactions. As already explained, legal citizenship does not necessarily guarantee access to cultural citizenship. Cultural citizenship is the ability to “blend in” and participate in collective expressions of national identity without challenges to whether or not you belong. It is a feeling of belonging and acceptance as part of a national community. Hence, we “perform” our cultural citizenship and belonging in everyday interactions. Multiracial ethnic-Danes’ lived experiences show that access to cultural citizenship is limited for non-White ethnic-Danes because they are racialized by White ethnic-Danes as foreign, hampering their sense of belonging and identification as “authentic Danes.”

Contrary to the official narrative, my research shows that legal citizenship or immigration status does not, in practice, define the boundary around who is or isn’t Danish. In everyday interactions, it is racial phenotype and skin color that determine access to cultural citizenship and belonging. Race matters in Denmark because racialized understandings of ethnic groups permeate both institutional and social structures. Nordic Exceptionalism is the ideology that sustains White hegemony and justifies discrimination of non-Western immigrants and minority racialized Danes—including multiracial Danes with multigenerational Danish heritage. It is an ideology that justifies and sanitizes the use of racialized language surrounding immigration and ethno-racial diversity. Race matters in Denmark because the obtuse rejection of race as a socially constructed category is a threat to legal and social equality, and to a cohesive national identity.

Further recommended reading on the subject

- Peter Hervik, ed., Racialization, Racism, and Anti-Racism in the Nordic Countries (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

- Suvi Keskinen et al., eds., Complying with Colonialism: Gender, Race and Ethnicity in the Nordic Region (Routledge, 2016).

- Rikke Andreassen and Kathrine Vitus, Affectivity and Race: Studies from Nordic Contexts (Routledge, 2016).

- Karim Murji and John Solomos, eds., Racialization: Studies in Theory and Practice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Rebecca C. King-O’Riain, et al., Global Mixed Race (New York: New York University Press, 2014).

- Nicole Stokes-DuPass, Integration and New Limits on Citizenship Rights: Denmark and Beyond (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015).

About the author

Mette Evelyn Bjerre is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Notre Dame. Prior to her doctoral studies, she received an M.A. in sociology from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In 2020-2021, she was a dissertation fellow at the Nanovic Institute. Her research focuses on race, ethnicity, and immigration. She is interested in how changing demographics due to immigration impact the social construction of race and between-group race relations. She investigates how racialization processes and interactions with the state influence individuals’ self-identity and how racialization processes impact the development of other social identities.

Originally published by at eitw.nd.edu on January 25, 2022. Europe in the World provides accessible analyses and commentary on Europe’s political, social, and economic relations with the rest of the globe. It is a platform for scholars of Europe to present their ideas in a form that helps bridge the gap between the academy and the general public.