Between 1954 and 1961, the United States made the highly unusual decision to sue the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies six times in the International Court of Justice. With the support of the Nanovic Institute, Steven McDowell (Ph.D. candidate, Political Science) traveled to the National Archives in College Park, MD, to determine why the United States would attempt to use international law to resolve sensitive disputes with a formidable set of adversaries in the 1950s. There he discovered a treasure trove of documents that helped illuminate the United States' perplexing behavior.

The information gathered during this research trip is sufficient for writing an article publishable in a number of history, international relations, or interdisciplinary journals. Furthermore, it will form the core of a future book project telling the full story of the litigation policy. These prospective publications will enhance my credentials as a scholar and prospective academic.

On March 3, 1954, the United States government instituted proceedings in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Hungary and the Soviet Union. Later in the 1950s and early 1960s, the U.S. also sued Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, both allies of the Soviet Union. The United States demanded monetary compensation for the loss of a downed military aircraft and the release of imprisoned crewmembers. Each proposal for litigation was rejected by the Soviet bloc. The aircraft in question were highly sensitive and some were engaged in surveillance activities. Yet the U.S. insisted on attempting litigation, despite the public nature of judicial activity and the reluctance of the Soviet Union and its allies to engage with the international judiciary. After 1961, the U.S. practice of suing the Soviets and their allies abruptly ceased. My project seeks to ascertain why the U.S. program of litigation began, how it developed throughout the 1950s, and why it ended abruptly after Kennedy took office in 1961.

Historiography on this string of Cold War adjudication attempts is sparse. Existing studies of the Eisenhower administration highlight the internationalist bent of Eisenhower and his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles. However, the ICJ cases mentioned above are rarely, if ever, discussed in these works, and it remains unclear what the U.S. was attempting to accomplish by suing these countries during a period of heightened international tension. For historians of Eastern Europe during the Cold War, these six ICJ cases represent an untold chapter of the history of the Cold War in Europe.

National Archives in College Park, MD

National Archives in College Park, MD

As the front lines of the Cold War in Europe solidified, the U.S. quietly attempted to use law as a tool for managing conflicts with Eastern European states situated firmly behind the iron curtain. What was the logic behind this policy? Why did it cease? Do the answers to these questions change anything about how we understand the early Cold War? The answers to these questions are of interest for scholars of Europe and beyond. Moreover, general studies of the causes of international adjudication cannot explain why such a powerful state as the United States would sue a similarly powerful adversary, the USSR, over military confrontations. For scholars of international relations, this string of ICJ cases represents a major outlier for existing theories of international litigation and great power behavior. Powerful states usually avoid international adjudication because their superior bargaining leverage allows for the creation of favorable negotiated settlements. American attempts at ICJ litigation in the 1950s do not follow this theory. Additionally, the realist school of international relations theory contends that great powers like the United States do not subject themselves to international law. But the United States did try litigation, and its interest in doing so is impossible to ascertain without additional research.

My research trip to the National Archives successfully answered most of my research questions. Files compiled by Samuel Klaus, an Assistant to the Legal Advisor of the U.S. State Department who served under the Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy administrations, contained an extensive documentary record of these cases. Jack B. Tate, acting State Department Legal Adviser under Truman, delegated responsibility for constructing international court cases against the Soviet Union and its allies to Klaus, who recorded his activities meticulously. Klaus’ files show that he originated the ICJ litigation policy in concert with Tate and other officials in the Department of State. The plan was to use overtures for ICJ adjudication for their propaganda value. The Soviets and their Eastern European satellites were unlikely to agree to the U.S. proposals, and this was known to the State Department prior to the first litigation attempt in 1954. Klaus, along with his affiliates, believed that forcing these countries to refuse adjudication in a formal manner would demonstrate to the world the tyrannical and arbitrary nature of the Soviet bloc. This, in turn, would encourage neutral countries to ally themselves with the United States while shoring up the allegiance of states already so aligned. The outcome of the case, or even whether adjudication occurred at all, was immaterial.

My research trip to the National Archives, supported by the Nanovic Institute, was extremely useful for my current project and for my future progress as a scholar.

The litigation policy developed into a routine strategy as the 1950s progressed. The Klaus files show that the policy was supported by the National Security Council (NSC) and the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB), both of which answered directly to the president. Multiple press releases from Eisenhower and Dulles express support for the ICJ strategy. The policy came to an end in the early 1960s for three apparent reasons. First, domestic politics intervened. Particularly in the final case against Bulgaria, Congress questioned the value of the ICJ suit. The failure to repeal the Connally Amendment, which affected the extent of ICJ jurisdiction over the United States, also made further litigation against the Soviet bloc unfeasible. Second, heightened tensions between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. in 1961 caused both sides to agree to drop outstanding claims in the ICJ, thus limiting the number of possible flashpoints. Finally, Samuel Klaus, already marginalized by the Kennedy administration and congressional intervention, passed away in 1963. Thus, the litigation policy died in the early 1960s.

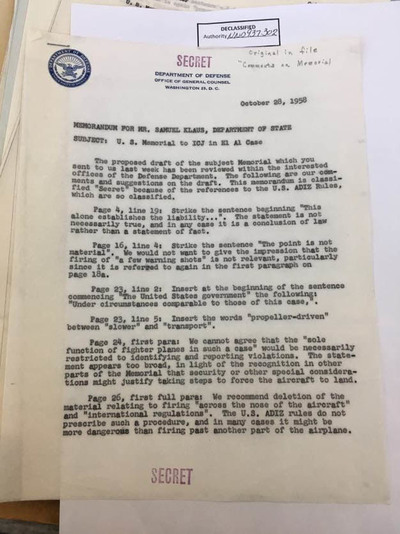

A once-classified Department of Defense memo to Klaus and the State Department detailing changes to a memorial to be sent to the International Court of Justice

A once-classified Department of Defense memo to Klaus and the State Department detailing changes to a memorial to be sent to the International Court of Justice

These findings are significant for scholars of international relations and Cold War history. In these six cases, a powerful state attempted international litigation, not for dispute resolution, but for its strategic value as propaganda. This contradicts rationalist scholars who portray international adjudication as the result of a lack of material power, democratic domestic politics, or even the failure of other settlement methods to resolve a dispute. However, the Klaus documents support constructivist scholars who use norms and policy analysis to explain state behavior. My novel contribution to this field lies in connecting these normative frameworks to a specific outcome (i.e. litigation) and in demonstrating that norms connected to international law can and do alter the behavior of great powers like the U.S. in conflict with powerful opponents. For historians, the history of the 1950s litigation policy is a hitherto untold narrative occurring during the formative decade of the Cold War. Additionally, the evolution of the policy from germination to maturity to its final end in the 1960s reflects the presence and decline of Progressive faith in “rule by experts” in the wake of the Second World War. Indeed, the litigation policy complicates narratives regarding the evolution of U.S. attitudes towards international law and power politics in the post-war context.

The information gathered during this research trip is sufficient for writing an article publishable in a number of history, international relations, or interdisciplinary journals. Furthermore, it will form the core of a future book project telling the full story of the litigation policy. These prospective publications will enhance my credentials as a scholar and prospective academic, particularly as their qualitative methodology represents a significant departure from my earlier statistical work. Finally, the trip was my first experience with extended archival research, apart from a brief trip to the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley for the same project. I hope to use this knowledge in future projects related to international litigation and state behavior. In sum, my research trip to the National Archives, supported by the Nanovic Institute, was extremely useful for my current project and for my future progress as a scholar.