Prof. Cotticelli is Professor of Theatre Studies at the Università della Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli." As a Fulbright Distinguished Lecturer, Francesco Cotticelli is teaching a course about the rise and establishment of commedia dell'arte until the first attempts of theater reform in Carlo Goldoni's early plays. This theme is related to his ongoing research, pursued now at Notre Dame, into the concept of reform applied to music and theater in the eighteenth century and the role which performing arts played in the European "enlightened" world.

Prof. Cotticelli, your research in the history of theatre in Europe is based in Naples but is hardly confined to it. Can you explain why?

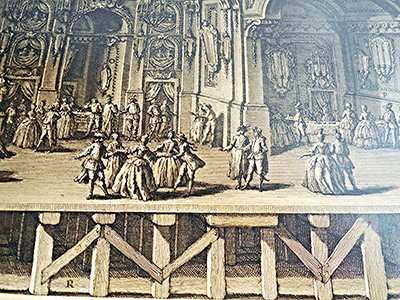

Yes, I am interested in eighteenth-century theatre in Italy, but I take a European perspective that seeks to understand its diffusion across Europe. The tradition of the Italian commedia dell'arte for example crosses many borders. A colleague of mine at the University of Vienna for example are tracing this diffusion across Europe, not just in the usual texts like Don Giovanni, but in actual theatres, where written plots were transformed for any number of reasons.

So your perspective has to be multidisciplinary.

Absolutely. The history of European theatre requires you to investigate not only the history of materials used in theatres, but the history of ideas, philosophies, and cultural norms. For example, how do we explain "moral corrections" to plots as theatrical performances travel from one region of Europe to another? We have to explore personal relationships, particular actors, even the technical possibilities or limitations of a specific theatre or stage. Any philological question has to face this highly technical reality, which is always related to the inner world of the theatre. No reality is meaningless when it comes to history. So to write history, you always have be thinking on at least two levels.

On at least two levels and probably across several levels as well, if I understand your historical work in Austria.

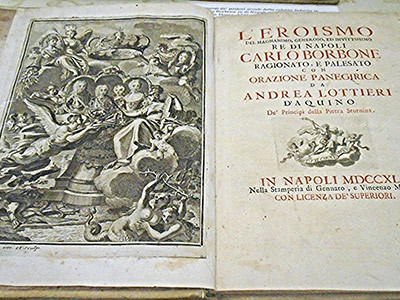

Very much so. My broadest professional interest is in Naples as a cultural center, with an emphasis obviously on the performing arts. But you have to remember that in the period I study, Naples was first a vice-royalty of the Spanish crown. At one point, it was even the largest city in the Spanish empire and the home of great artists like Caravaggio and Bernini. Then it came under the rule of the Bourbons, and then briefly a Republic before Napoleon. All these conquests meant that the cultural history of Naples is not always to be found in Naples! For example, many archives of our city theatres have been lost -- but we can reconstruct them from financial documents in Bourbon capitals like Vienna. For this reason, my colleagues and I have presented our work at the Salzburg Festival when it focused on Neapolitan musical culture and its dispersion.

I should think not many people today would even put those two cities in the same sentence. They seem so different: Vienna, the city of Mozartian refinement; Naples, the capital of Baroque in full fleshy flower.

As a Neapolitan, I have always loved German. To me, it is like Latin or Greek for the modern world. I started studying it in the liceo classico and have been very fortunate to have spent so much time in Vienna, which I love. But it is interesting: both Naples and Vienna as cities lost their roles as political capitals -- Naples in 1861, and Vienna in 1918. I am fascinated by the way each city retained and maintained its cultural dignity, proving that by losing a political role, you can bring forth a new one. Unfortunately, my city was not able to understand that at the right time.

What do you mean? How do Neapolitans think about the cultural identity of their city today?

You can perceive in them a nostalgia for the old grandeur -- even among the cosmopolitan young! -- but it's more often just an awareness of the past that allows them to recover their sense of dignity.

Are they fieri [proud], then?

Yes, but not in a negative sense.

Not orgoglio...

No. Fiero is good! Etymologically, it comes from feroce.

Tell me about your teaching. You have held postdoctoral positions in Italy, Spain, and Germany. How do you approach teaching non-Italians about Italy's cultural history?

Like many, I start with film. But it is only a start, because with film, you risk losing a real historical perspective. You have to understand, "Italian" culture is a recent invention because "Italian" is a recent invention. Public television was very aware of its role in establishing it across Italy after the Second Wolrd War, especially in the 1950s and 60s. "Italian" refers to a very complex system which deserves to be carefully analyzed.

Like the commedia dell'arte, I imagine, which I confess I only know about from caricatures in English theatre.

It is an interesting history. We know that troops in Vienna and Spain referred to commedia dell'Italiana. They used it as a category in theatre, but the words and category are younger than the phenomenon itself. I have found that students are highly motivated to learn this.

What accounts for the students' motivation?

I think it has to do with the fact that we've learned to train young readers and writers, but not TV watchers, internet users, and theatre-goers. We are obsessed with models for our behavior, but lack literacies to guide them. Look at social media. I think they are about finding your performing role in a community. Students find that learning the theory of theatre and its practical operation extremely useful. It would be great to have this kind of education in high schools.

Agreed. And once you email or perform something on the 'net, it tends to stay around for a while. The stakes of that can be quite high.

In some ways, theatre is an art that leaves no trace. Each performance is unique and cannot be repeated perfectly. But there is a lot to teach about the cultural interaction that does occur. For example, there was a wonderful conference in Portugal a few years ago called "Early Italy in the Modern Age: Slow Transformations." It focused on the social and political geography of style and repertoire and was fascinating too because, as you know, theatres were traveling shows and often had actors who also served as spies. So the theatre of history is bound up with the history of espionage.

This leads finally to your idea for a small giornata di studi here at the Institute during your stay. Could you say something about that?

I have in mind a graduate student and faculty workshop on the role of theatre in the political history of Europe. How did theatres intersect with diplomacy as their shows moved between cities and nations? There are many points of intersection here to explore. We shall see.