The following piece is by Eileen M. Hunt, professor in the Department of Political Science and faculty fellow of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies and the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. Hunt received a Nanovic grant for research, scholarship, and creative work to support her book project “Mary Shelley and the Spectre of Pandemic: The Origins and Development of Post-Apocalyptic Political Thought in European Plague Literature.” For more information on individual faculty grants, please visit the Nanovic website.

Summer 2021

London

Five days into a British-government mandated quarantine for international travelers to England, I feel like the last woman left in the existential limbo of the Covid-19 pandemic. Though fully vaccinated with two shots of Pfizer-BioNTech for almost two months now, I am required to take no less than five Covid tests in the space of three weeks to legally affirm what science has already proven: mRNA vaccines work to halt the spread of the novel coronavirus. Aside from the $600 total price tag for the tests (Thanks, Nanovic, for footing the bill!), and my very first PCR throat swab that made me involuntarily dry-heave on a sidewalk last Thursday in Southwark, I'm psyched to be back in Britain on my almost-post-apocalyptic and nearly post-pandemic research trip to study Mary Shelley's correspondence, journals, and other manuscripts related to her authorship of the first modern global pandemic novel, The Last Man (1826).

When I was awarded the Nanovic grant to travel to London, Oxford, and Hertford to study the lives and papers of Shelley and her correspondents, such as her fellow gothic writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton, I was wary of the obstacles to realizing my somewhat fantastical research proposal written mid-way through the long dark winter of Covid-19. I had originally planned to visit Italy, where Shelley lost three children she bore or cared for to the infectious diseases of dysentery, malaria, and typhus. But with the travel bans and lockdowns on the continent, I narrowed my trip to her homeland of England. Even then, the five-day quarantine, the serial testing, the uncertainty of new travel bans and lockdowns, and the resurgence of Covid variants all seemed to converge to make the trip seem impossible to plan. When one added in the labyrinthine process to apply to read manuscripts at the British Library in London and the Weston Library at Oxford, the very idea of the trip seemed preposterous.

My situation felt as absurd as the titular “Last Man”—or final human survivor—of Shelley's fictional global plague. While I had the luck of winning the grant to support writing a book about Shelley, plague literature, and the development of a modern post-apocalyptic aesthetic in literature and the arts, there were so many variables beyond my control. There was the possibility that the U.S. or the UK would change their international travel rules before or during my trip. I could be prevented from flying there, or back again. With the rise of the new Delta variant in Britain, I could—in theory—become infected with the virus despite being fully vaccinated. I could not know if I would test out of quarantine in time to do the work in the archives that I was here to accomplish.

On the eve of my flight across the Atlantic, the infamously campy words of Bulwer-Lytton sprang to mind: It was a dark and stormy night. And so, like Lionel Verney—the existential hero of The Last Man—I decided to go bravely into that good night. I was prepared for the worst but hoping for the best of comic adventure that only a post-apocalyptic trip can offer.

Quarantine upon arriving in Britain has been an exercise in government-mandated self-contradiction. Although I am required to self-isolate for five days, I have the option of going to a pharmacy or even an outdoor roadside lab to get my Covid testing done. If I elect the latter, how can I avoid doing things on the way? Especially tempting things, like buying croissants (and almond flapjack, and scones, plus a loaf of raisin bread for good measure) at the outdoor market next to the testing site? And getting a Rooibos tea and sitting in the sun while writing a paper about Shelley, Stoker, Orwell, Camus, and the ties between plague literature and existential philosophy? As I type and sip my tea, I feel like a character in literary cross between a Heller novel and a Sartre play: I'll be spiritually damned if I stay in my flat and wallow in my solitude, and yet I could be legally condemned if I break the nebulous self-quarantine rules by choosing an on-site testing provider from a government-approved list.

The silver lining of my Catch-22 quarantine is that I've accomplished a lot of things that would have been impossible under normal circumstances.

First off, I've consumed gallons of herbal tea. I've compulsively hit the trigger on the kettle to keep myself occupied in my studio apartment while I'm not typing or liking random stuff on Twitter.

Next, I surprised the government official who knocked on the door on day four to find me actually self-isolating and wearing a mask to boot. Apparently Big Brother is still alive and well—but conducting in-person, not remote, surveillance.

On the plus side for British manners is that the nice chap asked me politely if I needed “any support” after handing back my passport. Yes, please, I thought, I'd like lots of support. Company, conversation, and more groceries from the local Sainsburys than what my handbag could contain when I last shopped on the way back from my day two Covid test. And, while you're at it, get me a piping hot espresso-based beverage (with almond not cow’s milk). As much as I love the peculiar UK cultural ritual of reanimating the freeze-dried capsules of Nescafe instant coffee with tap water boiled by my oldest British friend, the plastic electric kettle, it’s high time for a grande American-style latte. Pronto.

What I actually say is Thank you, sir, as if I'm a clueless character in a Wildean comedy of manners, unaware of the absurdity of my social predicament as the last vaccinated woman under lockdown abroad. After all, I could be fined up to ten thousand pounds if I am caught breaking the (admittedly redundant) rules of self-isolation before I (the last vaccinated woman in self-quarantine) inevitably test out on day five. I'm pretty sure Nanovic would not cover that expense. And even if it did, by the good grace of the Institute staff, it surely wouldn't make it through the firewalls of Notre Dame accounting.

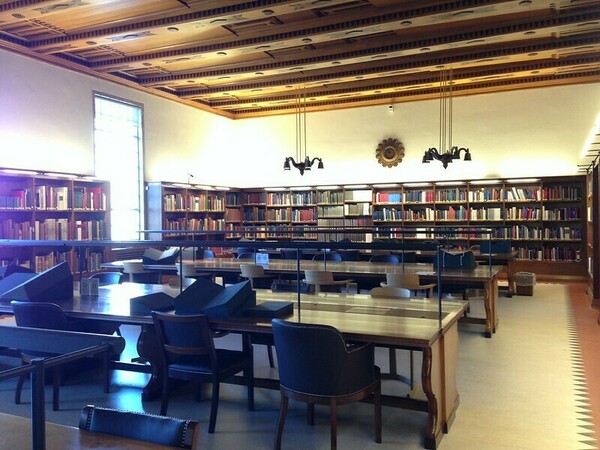

Thanks to the generosity of the staff at the Weston Library, I’ll have the astonishing opportunity to read Mary Shelley's journals, a treasure of British literature. I’ll also have the chance to see her understudied translation of Sophocles’ tragedy born of the Peloponnesian War and the Plague of Athens, Oedipus Rex. Both of these plague narratives—or stories of disaster and other extreme hardships—shaped Shelley’s writing of the first major modern post-apocalyptic novel, The Last Man. And the study of her study of them will undoubtedly continue to shape who I am, how I think, and what I write. What I keep telling myself—as I sit alone in my studio and write a paper on Mary Shelley's impact on post-apocalyptic, existential, and dystopian literature, film, and painting, for five days straight—is that some things in life (and academic research) are worth the risk, despite the hardships they entail. At the Hertfordshire archives, I’ll see the papers of the Member of Parliament Bulwer-Lytton, including his correspondence with Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin, as well as the Romantic artist John Martin, who began the first major post-apocalyptic painting based on her pandemic novel in 1826 and exhibited it at the Royal Academy in 1849. I’ll visit the British Library to study the history of the production of editions of The Last Man. In the rare books and manuscripts department, I’ll see a copy of a recently discovered unpublished letter from Mary Shelley to the Benthamite and editor John Bowring, as well as the journals of her sister Claire Clairmont.

About the Author

Eileen M. Hunt has taught political theory at Notre Dame since 2001 and has been a Nanovic faculty fellow since 2003. She is currently writing the concluding volume in her Penn Press trilogy on Mary Shelley and political philosophy, The Specter of Pandemic. The other volumes are Mary Shelley and the Rights of the Child (2017) and Artificial Life After Frankenstein (2020). She is grateful to the Nanovic Institute for supporting her archival research on Shelley and also the bicentennial conference on Mary Shelley's Frankenstein held at Notre Dame's Rome Global Gateway in 2018.