I noticed pedestrians were often impatient during my days at the Hague, waiting for winter to end, the wind to ease, and the sun to reappear. March meant unpredictable weather, as I realized when the warm morning that inspired my trip to Delft turned to gray clouds by the time I arrived. Wandering into Delft’s main square, I came across the statue of a man often mentioned in my international law course. I read the name “HUGO GROTIUS” embedded onto his pedestal and then looked into his steady, marble gaze. What would the father of international law himself have to say about the international criminal trials in the Hague, and what guidance would he prescribe to a young scholar eager to delve into the fields of peace and justice?

For four days I sifted through documents and footage at the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). My research sought to understand what role European politics play in the ICTY proceedings themselves, analyzing how the case of one war criminal--Radovan Karadžić--summoned the power interests of the European Union, Serbia, Russia, and other actors of the international arena. Documents articulating elaborate statutes, rules of procedure and evidence, and administrative exercises piled on my desk and every page in my legal pad was scribbled over with notes. I wrote, “How have logistical and mundane details created spaces for political contestation and control? Why did the ICTY review and object to granting interviews with Russia Today? Did the decision to admit intercepts from the accused relate to internal politics of the ICTY or the external interests of other states?” and in haste began running my eyes through pages and pages of transcripts and trial reports.

Some days I scanned available footage; the courtroom exhibited cameras aimed on the stand, interpreters whispering in the background, security guards with hands rested on radios and guns, journalists constantly watching from the public gallery, and everyone wearing headphones. Karadžić himself watches his own trial from the defense with an everyday sense of normality and mundaneness.

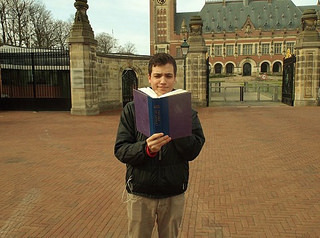

And then I pack up my papers and exiting through the lobby, I stop to glance at the TV monitor labeled “Trial Chamber III,” to see empty chairs displayed on the screen due to the postponed crossexamination. Speculating, I would find my way back to my hostel by the beach. I dozed in the tram and would gaze through the window to see embassies being closed and lamps beginning to light. A stop at the Peace Palace De Haagse tramnet always invited a crew of Dutch, English, French, Swahili, or Spanish speaking law students murmuring on their cellphones. A culture of international politics and legal justice constantly enveloped my experience not only inside the courtroom, but also in the very streets of the the Hague.

Exploring the legacy of the ICTY through its process--its subjectivities, spaces, and documentation--profited how I identify political spaces within international criminal justice. But in discerning its contribution to justice, I remember Grotius words: “Arbitration is where a matter ought to be left to the decision of a person, in whose integrity confidence may be placed, of which Celsus has given us an example in his answer, where he says, ‘I though a freedman has sworn, that he will do all the services, which his patron may adjudge, the will of the patron ought not to be ratified, unless his determination be just.’”