In the wake of the recent withdrawal of the United States from Afghanistan, commentators have drawn a flood of conclusions as to how such a decision foreshadows the future of U.S. foreign policy, particularly concerning Europe. In the decision, European leaders saw great cause for concern about the future of the U.S.-European alliance. First, the lack of cooperation and transparency between the U.S. and its partners with troops in the region raised questions of reliability and organization. Second, the move and its execution showed the similarities between President Biden’s foreign policy and that of the Trump administration. Finally, it seemingly signaled a general shift away from viewing Europe as a priority and a priority player. In the aggregate, the decision has contributed to a larger narrative that presents transatlantic relations as slowly deteriorating.

Fortunately, such dismal projections are likely overblown. The U.S. and its European partners, despite the recent discord, have sufficient shared interests to fuel the transatlantic alliance well into the future. A look to past instances when U.S.-European relations were strained because Washington unilaterally pursued its interests in other regions in the world—and at times even openly competed against its European allies—corroborates this view. Perhaps the most notable example worth revisiting from the past century is that of the Middle East—in the face of serious and sometimes confrontational disagreements over diverging regional interests, the U.S. and Europe still maintained extraordinarily close relations on the security of Western and Central Europe, that which was central to the transatlantic alliance.

The present quality of the U.S.-European partnership is often judged relative to its successes during the first two decades of the Cold War. The period is commonly regarded as the peak of transatlantic relations. When juxtaposed with the U.S. retreat from Europe following the First World War, the sheer amount of resources and political will devoted by the partners towards a common goal—namely, the security of Europe—remains difficult to fully grasp. Despite the costs imposed by the Second World War, Washington and Western European states remained committed to extensive cooperation and the idea of a shared fate. More than half a century removed from this era, the status of transatlantic relations is still, at least in part, measured relative to these perceived heights.

While it is true that the level of U.S.-European cooperation during the immediate post-war years marked a high point in transatlantic relations, this depiction of an impeccable partnership is an oversimplification. We tend to overlook the significant disagreements and disputes that existed between the two camps at the time, many of which concerned the Middle East. For example, when compared to the launch of the Marshall Plan and the development of NATO in Western Europe, U.S.-European relations on involvement in the Middle East appeared markedly less cooperative. Instead of coordination to promote general interests, the U.S. and Europe competed for limited resources and influence.

The primary point of contention at the time was the competition over spheres of influence in the Middle East between the declining empires of Europe and the rising superpower of the United States. This tension is exemplified by the first American involvement in the Middle East in the midst of the Second World War and the Suez Crisis of 1956. At the outbreak of the war, most of the region was under the domain, either directly or indirectly, of the British Empire. Having controlled Egypt since the 19th century, Britain’s acquisition of Iraq and Palestine in the wake of the First World War further solidified its authority over the region, albeit shared with French control over Syria and Lebanon. The discovery of massive oil fields, particularly in Iraq, further elevated London’s determination to maintain its rule. As such, the emergence of the United States as an increasingly involved player in the region was less than welcome.

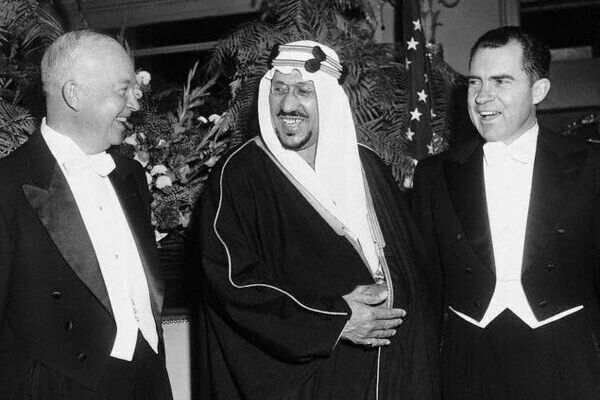

The beginning of U.S. engagement in the Middle East revolved around two issues that put it in competition with the British: oil and the shape of the postwar world. The origins of the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia, now its primary partner in the region, demonstrate this competitive stance. Concerned about future British expansion into the Arabian peninsula, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia sought an alliance with the U.S., in part to keep the British at bay. Beyond access to oil, the United States desired an alliance with Saudi Arabia due to concerns regarding continued British imperial ambitions. U.S. officials, particularly President Roosevelt, opposed continued European colonization both morally and from the position that it would undermine a stable postwar international order. An official alliance with Saudi Arabia in 1945 provided the U.S. with a foothold to accomplish both postwar goals. For the British, maintaining a colonial presence was crucial to their own postwar agenda. As a result, a natural point of conflict formed and the Middle East was transformed into a regionalized space of opposition between the United States and its closest European ally.

Disagreements concerning the Middle East did not, therefore, derail the aggregate transatlantic alliance. Both the U.S. and its European partners remained committed to cooperate extensively on the primary issue motivating the formation of such entities as NATO: Europe’s security.

Yet, despite this regional competition between Washington and London, American commitment to European security was strengthened, not weakened after 1945. The U.S. remained heavily involved in Western and Central Europe, committing billions to rebuilding Western European economies and maintaining a large troop presence. In kind, Western European states coordinated closely with U.S. policymakers to develop a joint strategy to counter the emerging threat of the Soviet Union. Disagreements concerning the Middle East did not, therefore, derail the aggregate transatlantic alliance. Both the U.S. and its European partners remained committed to cooperate extensively on the primary issue motivating the formation of such entities as NATO: Europe’s security.

The 1956 Suez Crisis was a much more visible rupture in relations. Since the war ended in 1945, European prospects within the Middle East had steadily deteriorated, particularly for France and Britain. Growing nationalist movements, like those in Egypt and Algeria, led to sizable losses in regional control and presented a distinct threat to the relatively little that remained of their global empires. As a response, Britain and France, in cooperation with Israel, launched an invasion of Egypt to regain control of the Suez Canal, a critical economic and strategic waterway that connects Europe and Asia. This was also designed to strike a blow to Egyptian President and prominent Arab nationalist Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The invasion ultimately failed, and it was the intervention of the U.S. against its European allies that ended the conflict. Though the U.S. and Egypt were not direct allies, the brazen invasion not only ran counter to American regional interests but risked provoking a response from the Soviet Union. Publicly, the U.S. used its diplomatic corps to join much of the world in condemning the invasion, culminating in a UN resolution. Privately, President Dwight Eisenhower threatened to take significant actions to harm the British economy, specifically undermining the British currency, if the Europeans did not withdraw. Realizing that the loss of American financial backing would be devastating, the British-French coalition ended the crisis with limited conflict.

Yet again, the disagreements over Suez did not hamper the larger transatlantic alliance. American military and economic support continued to flow into Western Europe and the European states continued to coordinate closely with Washington. In both stress periods, the transatlantic alliance thus displayed remarkable resilience. This resilience arose from the ability of both sides to emphasize issues that were of prime importance to them and in which there was substantial ground for common agreement. Despite at times competing against each other in the Middle East, the transatlantic partners engaged in extensive cooperation in Europe. Policymakers did not allow disputes over secondary issues to obscure and impede the possibility of coordination on what they believed mattered most.

Returning to Afghanistan, European unease over the U.S. withdrawal is understandable, particularly amidst disputed reports that the EU was not consulted. Nevertheless, the future of the transatlantic alliance does not look particularly bleak. Today, there are significant areas of mutual interest in which there is ample room for U.S.-European cooperation, such as climate change, countering Russia’s and China’s growing global influence, and global health. While the recent U.S.-French spat concerning Australian submarines exhibits the difficulties that still exist even outside of the Middle Eastern context, it is important for policymakers to continue the status quo by emphasizing those issues that are most critical and of common interest.

Further recommended reading on the subject

- James Barr, Lords of the Desert: The Battle Between the United States and Great Britain for Supremacy in the Modern Middle East (London: Simon and Schuster, 2018).

- David A. Nichols, Eisenhower 1956: The President’s Year of Crisis : Suez and the Brink of War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

- Chalmers Roberts, “Suez in Retrospect: Anthony Eden’s Memoirs,” The Atlantic (April 1, 1960), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1960/04/suez-in-retrospect-anthony-edens-memoirs/305585/.

About the author

Harrison Greenleaf is a second-year Ph.D. student at the University of Notre Dame, specializing in international relations. His research interests lie within international security, alliance politics, and U.S. foreign policy, particularly in Europe and the Middle East. At Notre Dame, he plans to focus on U.S. bilateral and multilateral security alliances, with a specific emphasis on comparing how the U.S. leverages NATO and Saudi Arabia alliances to pursue its broader security agenda. Harrison received his B.A. at Michigan State University, with a double major in international relations and political theory.

Originally published by at eitw.nd.edu on October 20, 2021.