He is a well-known figure in his native Ukraine: a Gulag survivor, a freedom fighter, and an advocate for freedom of thought. Myroslav Marynovych has been at the forefront of Ukraine’s quest for independence for over five decades. After spending almost ten years as a prisoner of conscience in the USSR, he returned to his homeland to contribute to the national liberation.

Marynovych talks about his life in a prison camp—or Gulag—often and recalls how the KGB state security officers who arrested him in 1977 for political dissidence made fun of his faith and his fight for freedom. A village boy, he grew up in a small town in Western Ukraine and began challenging the party’s iron grip when he was a teenager. Throughout his youth, Marynovych cooperated with other Ukrainian dissidents in the hopes of restoring Ukraine’s democracy and shedding light on the totalitarian regime in the USSR. He was only 29 when he was arrested in Kyiv for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda and sent to a prison camp in Siberia. There, he used every opportunity to participate in human rights protests, went on hunger strikes (including one that lasted twenty days), and passed his detention chronicles to activists on the outside. During his detention, Marynovych spent nearly 150 days in penalty isolation. In 1978, Amnesty International took him under their protection as a prisoner of conscience.

In 1984, Marynovych was moved to internal exile in Kazakhstan. There, he worked as a joiner and married a fellow Ukrainian, Lyuba Kheina, who he had met in Kyiv before his imprisonment. Lyuba moved to Kazakhstan to be with her husband and, upon his release in 1987, the couple returned to Ukraine.

Fighting for Freedom of Religion

Marynovych recalls that the KGB urged him to ask for forgiveness from Soviet authorities and threatened that he’d never be released. “A Kazakh KGB officer once asked me what I thought of Gorbachev’s perestroyka,” referring to the policy of restructuring the USSR’s political and economic system. “I told him I supported it because it would end with what KGB considered separatism, and what I considered national liberation,” says Marynovych, “[the] KGB laughed at me and said it would never end like that.”

As Marynovych predicted, perestroyka did end with the collapse of the Soviet Union. “In 1989, there was already a great feeling that the system was coming to an end,” the dissident says. “It was a huge year for Europe, and for Ukraine especially, when the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was legalized. It gave us a huge sense of freedom.” According to Marynovych, demands for religious freedom preceded any political demands. “It was a period of fundamental transformation,” he says.

The Greek Catholic Church was virtually unknown at that time. The biggest church in Ukraine at that time, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate, which benefited from support of the Soviet authorities due to its connection with Russia, inspired a lot of mistrust toward the Greek Catholics, whom they perceived as a challenge. “It was a big controversy in Ukraine,” recalls Marynovych, “there was even a narrative that the word “Catholic” comes from the word ‘Executioner,’” or kat in Ukrainian.

“Soviet authorities understood that it was impossible to stop Greek Catholics, but giving them their churches would be very dangerous,” Marynovych continues. The government initiated the creation of Autocephalous [or autonomous] Orthodox communities which would be given jurisdiction over churches that were historically in the possession of Greek Catholics. This caused a lot of misunderstandings between the two groups. Furthermore, Soviet authorities decided that Greek Catholics could only reclaim those churches where the priest and a majority of the members chose to convert to Greek Catholicism. “Can you imagine,” he explains, ”there is one village church, and some villagers want to turn to Greek Catholicism, and others don’t? That’s how you get conflicts.”

A Church for a New Republic

After the faithful decided on their church, tensions abated. In the aftermath of the Orange Revolution of 2004 and the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, the Orthodox and Greek Catholics established strong ties of cooperation. For instance, Ukrainian Catholic University and Open Orthodox University now work together through projects and conferences.

“Since neither the leadership, nor the faithful of the Greek Catholic Church wanted to conquer all of Ukraine and showed no violence, Ukrainians quickly understood that this Church was capable of development that mattered for the whole country,” says Marynovych. He believes that Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox in Ukraine now have the opportunity to realize the full potential of fruitful cooperation.

“[According to Marynovych, Western observers] have tended to underestimate the role of the Church during Ukraine’s most dramatic events even though it was—and remains—a very influential social force.”

“The Greek Catholic Church strongly promoted Ukraine’s transformation in the nineties.” Marynovych explains. “The fact that before demanding political freedom, people started demanding religious freedom shows the tremendous role of the Church for the change in Ukraine.” According to him, many Western observers have failed to notice how the 2004 and 2014 revolutions were also spiritual movements. They have tended to underestimate the role of the Church during Ukraine’s most dramatic events even though it was—and remains—a very influential social force.

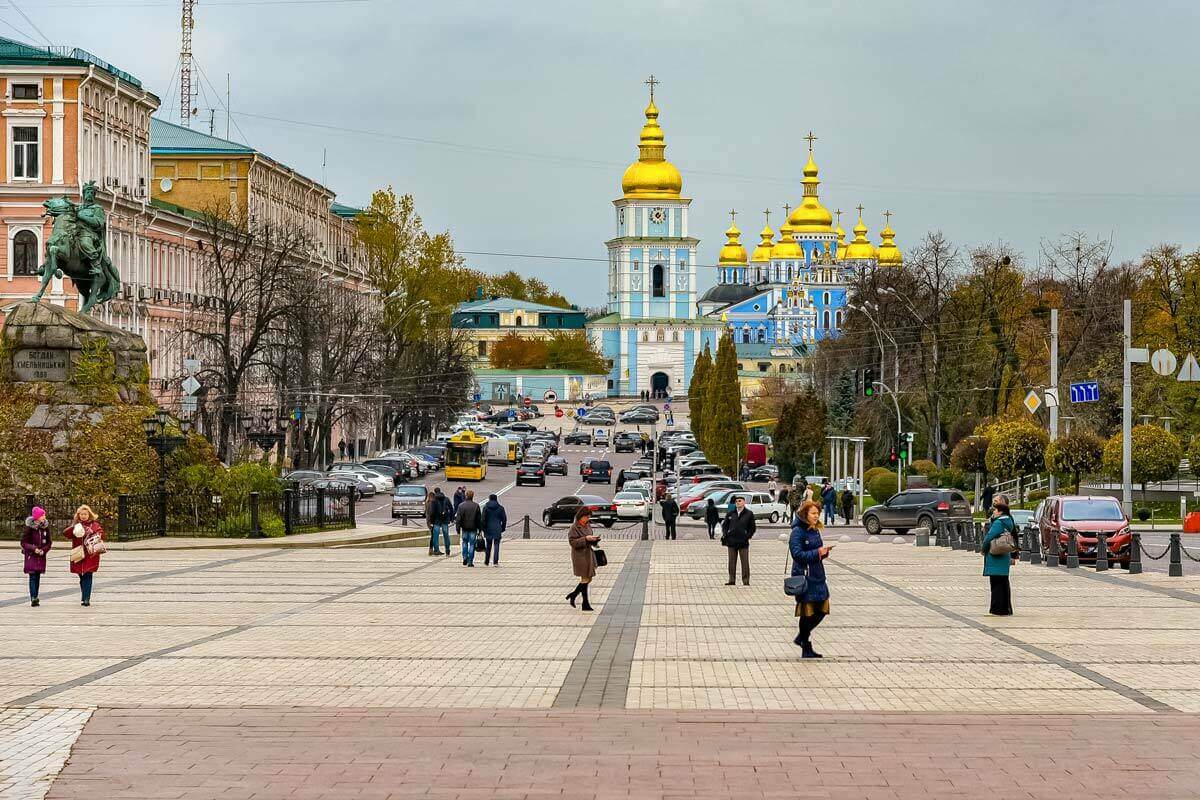

“During the first days of the Revolution of Dignity,” Marynovych recalls, “it was only students protesting on Independence Square. At first, they didn’t want any religious representatives giving speeches because they feared being manipulated.” Everything changed on the night of November 30, 2013, when then-President Viktor Yanukovych ordered security forces to remove all the protesters by force. During that bloody night, a nearby Ukrainian Orthodox church, Saint Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery, opened its gates and started ringing its bells. The wounded fled and hid there.

“This changed society’s perception about the Church completely,” says Marynovych. “It restored the Church's function as a shelter, a protector where you could hide. After this, Independence Square was open to all the churches [to support the protests]. There was an ecumenical tent, where anyone could come and preach. The image and place of the Church changed in Ukrainian society.”

According to Marynovych, this reliance on the Church in times of need is unique to Ukraine. He explains: “José Casanova, a renowned U.S. scholar in religion, concluded that Ukraine [is] the only European country with a competitive environment and American denominationalism. None of the religions are strong enough to diminish others, and none are so weak to be ignored by the state. Catholics, orthodox, and protestants have nearly equal power, and it’s a great benefit for Ukraine. The rites understand they cannot dominate, and they also understand they need one another.”

The dissident highlights that the Russian model, where a state favors one Church at the expense of others, would not work in Ukraine. “During his presidency,” Marynovych explains “Viktor Yanukovych wanted to prioritize [the] Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate. At that time, a group of protestants from Donetsk visited Ukrainian Catholic University. Coming from the home region of the then-president, they wanted to seek cooperation and solidarity with us to defend religious freedom. They were suffering from the Moscow Patriarchate as much as the Catholics.”

Confronting Challenges in a Transformed Ukraine

Now, the Church remains an important part of modern Ukraine although its role is changing. For example, there is a clear separation of state and religion, which is good and bad for Ukraine. Marynovych highlights the need to fight corruption as evidence of this challenge. “While the priests condemn corruption in all forms, more can be done about it. There can be an ecumenical call to stop corruption so all religious organizations launch a campaign against it. It has not been done yet, and I don’t know why. I believe the Church will eventually get to it.”

Therefore, although the Church has contributed to great transformations, independent Ukraine continues to be plagued by the remnants of the past. “We still live according to the values of survival, and not self-realization and development,” Marynovych says. “This transformation is the hardest one, and we still have a problem with it.”

On the bright side, Marynovych no longer sees the shadow of communism in Ukraine. “In the early nineties, I would automatically compare Ukraine and the West. I would see the calmness and peace there while Ukraine was so restless, so tormented. I don’t see these differences as much now, and the traps that I notice in Ukraine are also present in the U.S. and everywhere else,” he explains. “In America, the truth is divided into two extremes which fight with one another, and I see such cultural wars across the world.”

One of the ways to battle these cultural challenges is through education and stronger international ties. A proud example for Marynovych is Ukrainian Catholic University, where he is vice rector. The top-ranking school in Ukraine is the first Catholic university opened in a former Soviet country thanks to the support and vision of the Ukrainian diaspora in Europe, the U.S. and elsewhere. Now, UCU has strong ties with the University of Notre Dame. The relationship between the universities was formalized in 2019 with the signing of a memorandum of understanding on the occasion of the Notre Dame Award being presented to UCU President Archbishop Borys Gudziak. This agreement followed years of collaboration, particularly through the Catholic Universities Partnership, which is administered by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies.

“I feel that the partnership between Notre Dame and Ukrainian Catholic is wonderful; it’s been in place for many years. We have many challenges in common such as anti-culture, post-truth, and fake [information].” For Marynovych, “Our challenges make us think how faith can resist these threats.”

About the Author

Anna Romandash is a Master of Global Affairs student in the Keough School of Global Affairs, majoring in International Peace Studies. She is an award-winning journalist from Ukraine, who has worked as a reporter and digital policy expert focusing on sustainable media development, human rights, and information access. Romandash was named Media Freedom Ambassador of Ukraine for her human rights and media work and is the recipient of a Kroc Institute Fellowship.

Originally published by at crossingthesquare.nd.edu on November 23, 2021.