My love language

Halyna Kruk

my love language has broken teeth

spit, you say, spit ‘em all out, spit ‘em quick!

you’ll get straighter ones.

with a better bite.

my love language is a wreck,

avoid this thicket, it’s mine upon mine, a tangle of tripwires,

you never know what a word really means,

which memory you can touch, which will detonate.

we planted this hedge so no one would get hit,

hung caution signs to warn the others

of death disguised as a pretty view

but you just offer to remove them so nothing

ruins the picture, not waiting for the sappers,

not clearing the empty terrain of thorns.

my love language is heavy as a father’s gaze,

immovable as the eyelids upon his son’s coffin,

which they used all week to steady their guns,

my love language is choking on its words like his mother

I held it close when I was crying and to stop crying,

I held it close. I knotted it like a camouflage net,

color coordinated with the season, so it could

hide someone.

you say don’t get mad. be wiser. take the high road.

tame your love language. push it out. purge yourself of it.

plant a flower in this scorched land.

in this empty place in the language and in you

you must have saved a few flower seeds.

you must have saved a kind word someplace.

someplace in your soul, that will forgive everything

my love language has grown so big

that my tongue comes out with it,

and my soul come out

with this soulless language.

у моєї мови любові вибиті зуби

виплюнь, кажеш, усе це із себе, виплюнь негайно!

тепер можна вставити набагато рівніші.

із правильнішим прикусом, ніж попередні.

у моїй мові любові не лишилось живого місця,

не заходь у ці хащі, там міна на міні, суцільні розтяжки

ніколи не знаєш, що насправді тягнеться за словом,

який спогад зачепить, а який здетонує.

ми насадили цей живопліт, щоб ніхто не наражався,

навішали попереджувальних знаків, щоб уберегти інших

від смерті, замаскованої гарним пейзажем

а ти пропонуєш їх просто прибрати, щоб нічого

не псувало картинки, не чекаючи саперів,

не розчистивши цих теренів від пустих теревенів.

моя мова любові важка, як погляд батька,

непідйомна як віко на гробі його сина,

на якому тиждень пристрілювали зброю,

моя мова любові вдавилася словами, як його мати

я плекала її, доки плакала і щоб не плакати більше,

плекала. я плела її, наче маскувальну сітку,

відповідно до кольорів пори року, щоб вона когось

захистила.

кажеш, не ятри. будь мудрішою. будь вище від цього.

присмири свою мову любові. вижени. вирви із себе.

посади на цій випаленій території квіти.

на цій порожній місцині всередині себе і мови

у тебе ж мало залишитися десь насіння квітів.

у тебе ж мало десь залишитися добре слово.

десь за душею, що має усе прощати

моя мова любові так розрослася,

що виривається тільки разом із язиком,

що виривається тільки разом із душею,

бездушна

Analysis by Andriana Opryshko, with Lindsay Burgess

“War makes everything so straightforward that almost no room remains for poetry – only for testimony.” – Halyna Kruk, Berlin, June 2022.

Halyna Kruk is a Ukrainian poet from Lviv and a member of PEN Ukraine, a national branch of an international association of writers that defends freedom of expression. Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, which marked the beginning of the contemporary Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kruk has been writing about the conflict and drawing attention to the crimes of the Russian army.

Kruk published “у моєї мови любові вибиті зуби” (“My Love Language Has Broken Teeth”) in 2020 as a reflection on Russia’s war in Ukraine, which began long before the full-scale invasion of February 2022. The poem reveals a number of themes including silences and testimony in wartime, and the ways in which trauma makes it difficult to understand or feel love. The atrocities of the war change the perspective so drastically that they might twist the concepts of love and hate, making them almost indistinguishable. Kruk’s poem narrates these alterations, depicting the changes in love and the appearance of hate. Exploring the right to testify about the crimes of the Russian army and the way in which this experience has transformed how its victims feel and express love, the narrator discovers the right to hate and laments over the tragedy of the Ukrainian people. As the narrator gives expression to their love language, they convey an almost physical pain and signs of trauma that they hold in common with Ukraine and its people.

Kruk raises a crucial point about silencing the victim. In one sense, the poem’s narrator is rebuking an international political community that, for several years, encouraged Ukraine to be more tolerant and conciliatory toward their increasingly aggressive Russian neighbor. The first line, “my love language has broken teeth,” gives a sense of the victim’s muteness and inability to testify to their abuse and alludes to a physical trauma — a punch to the face — that comes from an attacker who is physically close to the victim. In light of Russia’s naked aggression, particularly since 2022, this poem speaks to the urgent need to provide testimony, even though it might be cruel or even hateful in tone.

Kruk’s poem uncovers the reasons why war turns the language of love into the language of hate, and exemplifies how to give this process expression in poetry. The author works with the complex notion of trauma affecting the narrator’s perception on different levels. The narrator compares their mind to the “thicket” with “mine upon mine, a tangle of tripwires.” This suggests that the narrator’s love language shares the trauma of the Ukrainian land, some areas of which will remain scarred and peppered with landmines for decades. The poem also highlights collective trauma. This is evoked through the universal image of a funeral, allowing her to represent the burial of a loved one as an experience that connects all victims of war, and even those observing this war from the outside. In her poem, Kruk’s love language is described using words such as “wreck,” “heavy,” “immovable,” and “choking.” In these ways, the traumas presented in this poem manifest themselves through emotions that were solely expressions of love for family, friends, and allies that have been transformed into something resembling hate for one’s enemies.

Using familial relationships, Kruk depicts their complexity by exploring what happens to love shared during times of war. Kruk uses strong imagery to illustrate the scene of two parents, heartbroken, as they look upon the coffin of their son who died fighting on the front lines for his country. The soldiers he fought with use his coffin as a physical support and emotional motivation to take aim at the enemy as they make a dangerous journey to bring their comrade’s body home. This family unit should be the locus of the first and strongest love a person experiences, and we see this love through the love the parents have for their son, the love the soldiers have for their fallen brother-in-arms, and the love the son had for his country. However, the love also takes on a nuanced hate toward the enemy, depicted through the father’s heavy gaze as he looks upon his son who died at the expense of the enemy’s war, the mother’s visceral choking on her words due to the grief she faces, and the soldiers’ pain in losing a fellow soldier by enemy fire. There is a closeness between love and hate in wartime; an immense love for friends, family, a country, while the actions that cause grief, pain, and loss in war create a hatred for the enemy.

Research by: Andriana Opryshko and Lindsay Burgess

Poet: Halyna Kruk

Translators: Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk

Theme: Language of Hate and Love

"My love language" by Halyna Kruk, translated by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk, reproduced with permission.

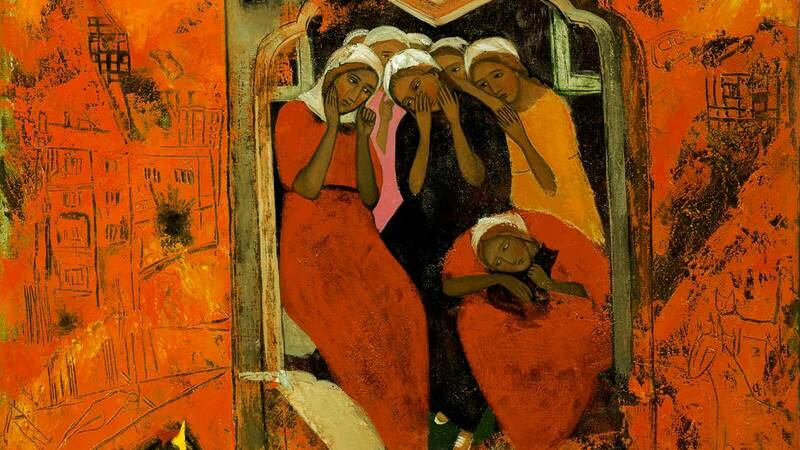

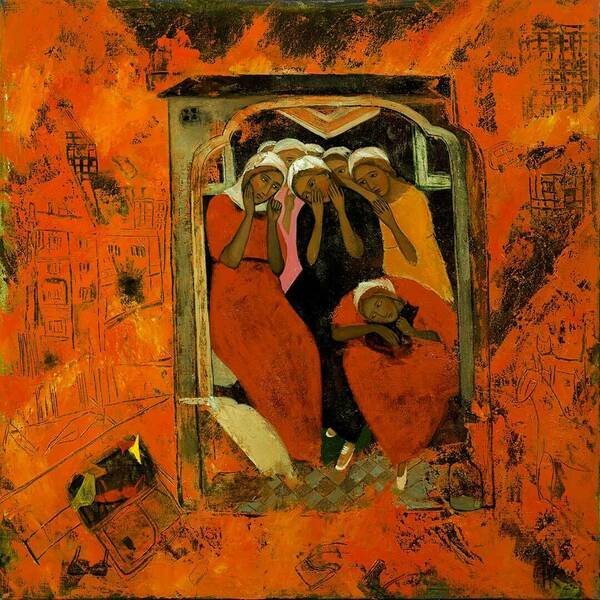

Header image: “Shelter” by Kateryna Kosianenko, oil on canvas, 2022. Image used with permission from Kateryna Kosianenko.