A guy I know volunteered ...

Serhiy Zhadan

A guy I know volunteered.

Returned six months later.

Where he was — I don’t know.

What he’s afraid of — he won’t say.

But he’s afraid of something.

It seems he’s afraid

of everything.

He was normal enough before he left,

maybe talked a bit too much.

About everything on earth,

About every little thing he saw in front of him.

But when he returned he was

totally different, as if

someone had ripped out his old tongue

and forgot to replace it.

Now he spends all day in bed

listening to demons in his head.

The first demon is fierce,

a fire-spitter, demanding

punishment for all living beings.

The second demon is mild,

talks of forgiveness,

speakputs his hands, smeared with black earth,

right on your heart.

The third demon’s the worst.

He gets along with both.

Agrees with both, won’t contradict.

Just his voice alone

gives you a migraine.

Знайомий пішов добровольцем.

Повернувся за півроку.

Де був – невідомо.

Чого боїться – не каже.

Але чогось боїться.

Може навіть здатись,

що боїться всього.

Йшов нормальною людиною.

Говорив, щоправда, забагато.

Про все на світі.

Про все, що траплялось на очі.

А ось повернувся

зовсім іншим, так ніби

хтось відібрав у нього старого язика,

а іншого натомість не залишив.

Ось він сидить цілими днями на ліжку

й слухає бісів у своїй голові.

Перший біс лютий,

сипле жаром, вимагає

кари для всіх живих.

Другий біс покірний,

говорить про прощення,

промовляє тихо,

торкається серця руками,

вимащеними в чорноземі.

Але найгірший – третій біс.

Він із ними обома погоджується.

Погоджується, не заперечує.

Сам після його голосу

і починається головний біль.

Analysis by Halyna Tuziak

Serhiy Zhadan published the poem “Знайомий пішов добровольцем. . .” (“A guy I know volunteered…”) in May 2017, three years after the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. This is a reminder that even though the full-scale invasion of Ukraine started in February 2022, Russian aggression began at least eight years earlier. In his poetry, Serhiy Zhadan combines Ukrainian futurism, a style of poetry that challenged Soviet cultural policy in the 1920s, with his personal experience and feelings in the context of Russia’s war on Ukraine a century later. Specifically, Zhadan is influenced by Mykhailo Semenko, a leading figure in the Ukrainian futurist movement whose execution by the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic in 1937 places him within the generation of Ukrainian writers, poets, and artists persecuted and purged during the Stalin regime and known as the Executed Renaissance. Zhadan, who wrote a thesis at Kharkiv Teacher’s College on Semenko and Ukrainian Futurism, has cited the executed poet's influence: “When you hold in your hands the lifetime editions of Semenko … you begin to treat them like relatives. Perhaps distant, but no less close to home.”

From the poem’s first line, the reader realizes that the subject is the short life story of someone very distant from the writer. Zhadan does not even refer to the lyrical hero as a “friend”; he is just “a guy I know,” an acquaintance. The name, the age, and the relation to the author are all unknown. This also creates a sense of distance between the reader and the soldier at the heart of the poem and yet, despite this distance, Zhadan creates an invisible connection between subject, author, and audience. When Ukrainians read the line “A guy I know volunteered…,” it immediately evokes the image of at least one of their own acquaintances who volunteered to fight at the front. In spite of barely knowing these individuals, everyone understands that they have been ready to sacrifice their lives for the freedom and the everyday life of civilians. It is precisely for this reason that this distant person becomes very close, important, and powerfully connected to each of their fellow citizens. This is what especially unites this piece with Vyshebaba’s “To my daughter,” analyzed by Abigail Keaney. Both authors are writing in this unique way of anonymity and universality as they are able to direct their words to each Ukrainian. Through this Zhadan and Vyshebaba are reminding their readers of the immeasurable value of freedom and the difficulties of the fight not only on the battlefield but also beyond and after it.

In the lines that follow, Zhadan maintains his distance from the soldier, resisting a more intimate tone by omitting any clear details about his subject. The reader learns the exact time of the volunteer’s stay at the front — 6 months — but everything else remains unknown. Despite this lack of specifics, the soldier, particularly his relationship with the authorial voice and the audience, transforms. Zhadan creates a feeling of anxiety and discomfort for the volunteer, a sense that the reader recognizes and empathizes with his sacrifices and suffering. Despite the relative anonymity of the guy we all know who volunteered, this soldier, as an archetype, is known to all Ukrainians. His dual obscurity and relatability echo the way in which many nations show respect and gratitude towards each and every soldier by, for example, installing and honoring tombs of unknown soldiers.

As the poem continues, Zhadan delves beyond the soldier’s external circumstances and explores his inner world, giving the reader a chance to find out about his concerns and worries. Zhadan achieves this through images of demons in his subject’s head. Again, the poet breaks the distance between the soldier and the reader, bringing the reader closer to the inner world of the poem’s hero. The demons represent how inevitably war changes and influences the life of each and every person who experiences it. There are three of them, all very different and opposite to one another. The fierce one, the mild one, and the neutral. These three demons are the artistic description of PTSD, a disorder that is unavoidable in such circumstances. Men who volunteer to serve in the army are often more motivated than those who are enlisted. They have clear reasons, realize the potential consequences, and possess inner strength and courage. Volunteers are very conscious of their choice, one that is based on their moral values and wish to fight for freedom and independence, and against terrorism. However even with this core strength, it is impossible to avoid the terrible effect that war leaves. Those who have seen the battlefields, blood, and murders will never be the same again.

Serhiy Zhadan’s poem is a reminder that freedom is invaluable. Through his poem, Zhadan opens the door to the future, reminding us that the struggle continues not only on the battlefield but also in each of us. We will have to fight not only during the active stage of war but also after the victory.

Research by: Abigail Keaney and Halyna Tuziak

Poet: Serhiy Zhadan

Translators: Virlana Tkacz and Bob Holman

Theme: The (un)Known Soldier

Theme Introduction Next Exhibit

"A guy I know volunteered ..." by Serhiy Zhadan, translated by Virlana Tkacz and Bob Holman, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

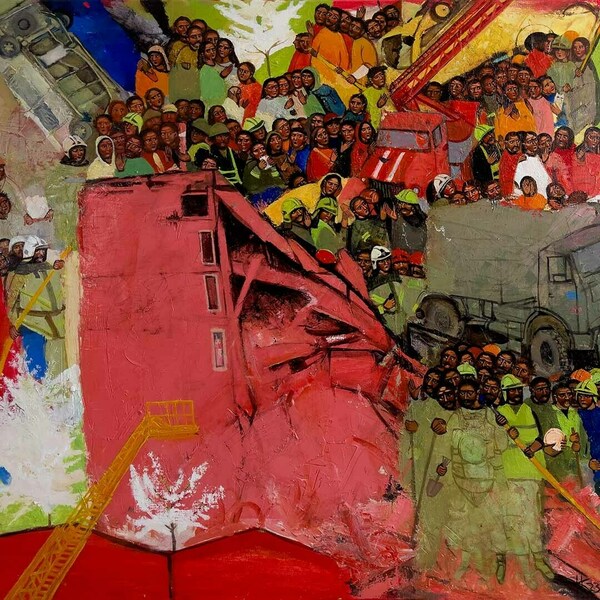

Header image: “Cherry Blossoms” by Kateryna Kosianenko, oil on canvas, 2023. Image used with permission from Kateryna Kosianenko.