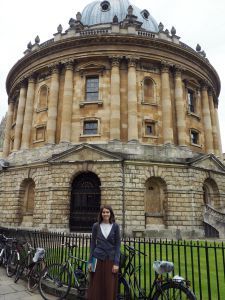

Mary Catherine Walter ('16) is an Architecture major who received an Undergraduate Travel and Research Grant from the Nanovic Institute. She spent a part of her summer traveling around the United Kingdom studying the concept of holistic design in medieval cities. She recently sent us a report on her trip, as well as some sketches. Take a look!

A well-formed community, whether it is the lively streets of Oxford or the quiet green of a rugged hamlet, has a clear and cohesive sense of character. One experiences the place with the anonymity of a reader who, leaving themselves behind, delves into a story that unfolds piece-by-piece along every turn, affected by every actor who enters the scene. The urban world communicates through an articulate grammar, visually linking clauses with passageways and terminating axes with a pronounced period. Such devices are used so that the city reads as a whole and flows naturally from street to street. The themes are evident, the motifs recognizable, but the plot is never boring; when told well it continually draws us through each space with curiosity until perhaps we even become contentedly lost in the pages.

The romance of the holistic city is not beyond further analysis, but to describe its parts without their connections is self-defeating. An interesting building or a beautiful park is worthless if they are so misplaced in their context that people cannot enjoy them. We pick apart a city because we wish to know how it is put together, so in my research I looked not for what the components are (market, church, green, etc.) but how they relate to daily life. In the United Kingdom I photographed, sketched, and walked in order to understand these relationships through firsthand experience. Experience is necessary because what we remember of a place is a caricature of its essence – the feel and density, the smells and sounds – and it is brought to new life when we imagine how it can be a model for the future.

In my travels there were predictable urban patterns (such as the close proximity of market and town hall) but it never felt monotonous. The variety of the medieval world masked under layers of modern change or celebrated in relics of stone and timber was striking. It was never repetitive and boring because there was character in both the architecture and the streets. The placement of buildings, for instance, on a street called West Bow in Edinburgh’s Old Town sweep dramatically up from the Grassmarket and out of sight as if daring you to discover what is hidden around the bend. In Durham I spotted a tiny hidden passage that happened to be the medieval pilgrim’s walk and a shortcut to the market and bridge. Surprise views and hidden gems such as these make streets exciting and memorable.

As a general note, throughout the trip I was reminded that the American conception of space is entirely different from everywhere else. Having lived abroad in Rome as part of Notre Dame’s architecture program I have been familiar with closer quarters but I was surprised how little I anticipated the tightness of the English lanes. Tall delivery trucks fly through narrow medieval gateways and in many villages drivers must swerve or stop to avoid the cars parked in the lane. Returning home to the suburbs it is almost comical how wide the streets are in comparison between the equally spacious residential setbacks. It is no wonder that our instinct is to start up the car when the streets are uninteresting to walk.

There are many advantages to bringing neighbors closer together, literally and figuratively. Everywhere I went I found markets that have functioned as gathering spaces for centuries and still promote communal activity. Teenagers with smartphones in hand sat talking on the steps of antiquated crosses and pedestrians caught without umbrellas found refuge in covered markets. The old market place in Wells has been multipurposed into a car park doubling as a farmers market on a weekly basis. These thriving spaces beautifully echo their original medieval uses, albeit in a modernized way appropriately adapted to the present era. It is not necessary that our cities have such an ancient history, but it is crucial to draw from these success stories and adapt spaces to bring people together.

The reason I chose to focus on medieval Britain is because medieval philosophy supports the idea of holistic design. The Medievals valued hierarchy and holistic thought, understanding that each part of a system is different and indispensible in promoting the good of the community as a whole. They recognized that everything, great or small, has an effect on and relationship with everything else. Their sense of hierarchy even transcends realms placing the spiritual world foremost over the earthly so that typologically sacred spaces are revered as such and not confused with commonplace businesses. It is in fact the medieval monastery that is the perfect urban microcosm. Self-sustainable, cohesive, and inclusive, the abbey attends to all its inhabitants’ needs. It includes supporting agriculture and craftsmanship, education, medical treatment, housing for religious and guests, spiritual worship, and a meeting house. Fountains Abbey outside of York was the most complete example I saw and it is impressive how much of a powerhouse the monastic world was before its dramatic decline.

Our culture today supports much of the trending design philosophy too. Modern buildings designed by “starchitects” value testing the latest technology and creating an individual aesthetic that must stand wildly out if it is to be successful. They are statement makers but only as beacons of segregation that disregard the integrity of their surroundings, shouting to be heard over their neighbors. Thankfully Notre Dame supplies an alternative education that teaches how to gain from the tested and proven past. I am very grateful for this opportunity to travel and observe the development of centuries of history from burghs and hamlets to towns and cities. I am confident that what I have gained from this experience improved my understanding of urban design and can be applied to the creation of beautiful places to be enjoyed by generations to come.