How can national embarrassment result in renowned cultural institutions? Kelly Marous (’16), a double-major in Political Science and French & Francophone Studies, received a Senior Travel and Research Grant to explore the German Occupation’s role as a catalyst in promoting French cinematic cultural exception. Kelly recently wrote to us about her experience:

My curiosity about the relationship between politics and film in France originated from my experience at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, made possible by a summer internship grant from the Nanovic Institute. I noticed that French cinema, at least what was present at the festival, was distinct from all other national cinemas, that l’exception française, French cultural exception, was alive and well, and that the nature of the entertainment industry in France was somewhat unique compared to those in the United States and in other European countries. I intend to argue through my senior thesis that the distinct “Frenchness” of French cinema that I observed at Cannes can ultimately be explained through war, more specifically through the Occupation. By evaluating film journals and government-sponsored bulletins from the CNC, the Center of Cinematography and the moving image, I address exactly how war gives film meaning to governments, to filmmakers, and to the conception of what film is.

Scholars of France and French culture, of film, and of politics have all explored exactly how the Occupation impacted the French film industry. Topics ranging from the political economy to film theory to social issues have been addressed in articles, books, and beyond. While this versatile insight is beneficial in understanding the immediate aftermath of World War II and the Occupation in French cinema, it does not provide a cohesive narrative of how the presence of the German Occupation is a prominent contributor to the reality of contemporary French cinema and to the notion of l’exception française within the film industry. These scholars have explored the effects of the Occupation, but its meaning to French cinema remains unexplored relative to its effects on French cinema.

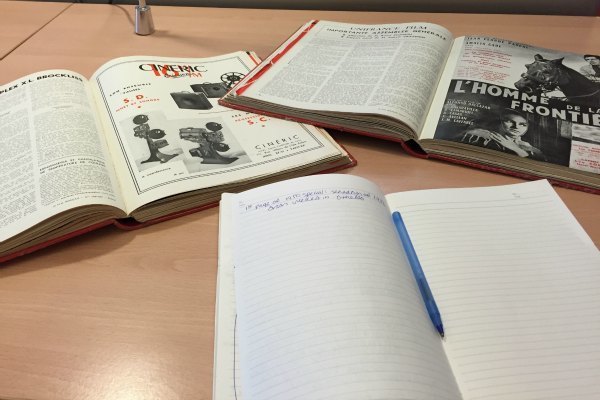

While in Paris, France, I visited the National Library of France (BnF) and the Cinémathèque Française to study various film journals and government releases pertaining to the film industry ranging from the postwar years to the beginning of the New Wave in the early 1960s. In studying publications of L’Avant-scène cinéma, Cahiers du cinéma, Le film français, La Revue du cinéma, and CNC bulletin d’information, I took note of what was published, how it was portrayed, and how this changed within a twenty-year timespan following World War II. While I was familiar with many of the trends I noticed throughout my research, such as the unanimous respect for Orson Welles or the increased presence of coproductions and of Italian films within French markets, being able to see the articles, the advertisements, and the figures firsthand emphasized both how potent and how present such tendencies were in the discourse of filmmakers and film critics, of bureaucrats, politicians, and economists, and of the masses in general. In addition to collecting figures regarding market shares, coproductions, and film attendance, largely from CNC bulletin d’information and Le film français, I also took note of how a “European cinema” developed in conjunction with the Treaty of Rome in 1958, how film critics spoke of the creation of the Cannes Film Festival, how auteur theory, made popular by François Truffaut, was discussed in law, and how relations with both the United States and Italy changed and were received by the film community in France.

One unexpected yet useful experience I had while in Paris was observing how film is valued and understood in contemporary France in ways different than in the United States, how film is another manifestation of l’exception française. I noticed, for example, that the BnF had its very own cinema, playing both Hollywood blockbusters and films of a higher caliber, such as Cannes film selections. In addition to finding an MK2 Cinema directly attached to the BnF, I also discovered that the Cinémathèque Française, which at the time hosted an exhibition on Martin Scorsese, was within eyeshot of the national library. The proximity of France’s ultimate center of learning and of France’s center of cinema reemphasized two key observations from my research thus far: that French cinema is an enshrined and respected institution in France and that discourse and collaboration with foreign filmmakers has become a defining characteristic of French cinema today.

My findings, both qualitative and quantitative in nature, reinforce prior findings regarding the evolution of French cinema since the Occupation. I believe that the observed changes in the economics and business practices of the industry, the creation or modifications of various institutions within the industry, and the challenges proposed regarding film aesthetics reflect not only the policies and expectations characteristic of Occupation France but also of what I observed at the Cannes Film Festival. The evolution of French film during the postwar period up to and through the New Wave provides a missing link from French cinema’s darkest times during the Occupation to one of its greatest times: today. The various statistics, articles, and advertisements that I uncovered while in Paris will help me explain how this is so.

As both a French and Political Science double major and a cinephile, I found the opportunity to study French cinema periodicals in Paris to be an incredibly valuable experience that complements both my academic work in the form of my senior thesis and my goals of making a career for myself in cultural exchange by working on behalf of governments, firms in the entertainment industry, or NGOs. I believe that my research will provide an authentic and original narrative of French cinema, a narrative that will help me understand the workings of French cinema, French-American coproductions, and cinema’s unavoidable relationship with the state and with war. I hope to use this more profound understanding of one form of cultural communication to market myself as an expert in this field.