“Do the people of London talk of me at all — what is the lie of the day? […] am I gone over to France on a treasonable embassy? am I teaching the United Irishmen the use of Arms? […] or finally have I retired upon an immense fortune collected in crooked sixpences[?]”

As it happened, the people of London did talk of Thelwall a great deal, especially after his (and Hardy’s) narrow acquittal in 1794 of a charge of high treason, instigated by the government of William Pitt to suppress the reform movement by making an example of its leaders. Having slipped the noose, Thelwall then boldly sidestepped government restrictions on political speech in 1796, advocating the rights of men, women, and slaves in transparently allegorical lectures on classical history. Even the King was informed of this open defiance of censorship.So inquired the British reformer John Thelwall (1764-1834) of his friend Thomas Hardy in May 1797, alluding to the notoriety he had acquired for his vocal defense of democratic principles during the time of the French Revolution.

But it was not just Thelwall’s political resilience that had people talking. His poetry, fiction, drama, journalism, and medical writings also sparked wide interest, notably in the young William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge. “Pursuing the same end by the same means,” Coleridge wrote in 1796, “we ought not to be strangers to each other.” Thelwall would sustain a mutually formative dialogue with the poets – in letters, conversation, and verse – for years to come.

Yet the “talk” about Thelwall, and indeed his own political voice, were eventually silenced, first by an increasingly muscular campaign of repression, and later by the loss of substantial portions of his archive.

The latter, however, is now being rebuilt as Thelwall re-emerges as a subject of lively scholarly conversation. A case in point is the May 1797 letter to Hardy quoted above, one of a series of eight letters between the duo that have just been acquired by the University of Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Library.

Long thought missing, these candid letters between two leading figures in the 1790s’ reform movement represent a valuable new resource for anyone interested in turn-of-the-century British politics and culture in a European context.

These remarkable letters can now be consulted in the University of Notre Dame’s Rare Books and Special Collections, where they find a permanent home alongside a first edition of Thelwall’s political journalism in the Tribune (1795-96). Their purchase was coordinated by Laura Fuderer, English and French Literatures Librarian, in consultation with Yasmin Solomonescu (Department of English), Judith Thompson (Dalhousie University), and Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC (President, John Thelwall Society), with support from the McGovern Family Collection in British Fiction and Criticism, the McCann Library Collection in English Literature, and the Mary B. Mathaus Endowed Library Collection on the Book and English Literature.

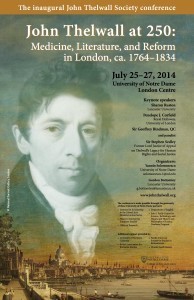

The letters’ acquisition will be celebrated at the conference John Thelwall at 250: Medicine, Literature, and Reform in London ca. 1764-1834, co-organized by Yasmin Solomonescu (Notre Dame) and Gordon Bottomley (Lancaster University), and made possible through the generosity of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, as well as the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, Henkels Lecture Series; the Office of Research; the Department of English; the John J. Reilly Center for Science, Technology, and Values; and the History and Philosophy of Science Graduate Program; as well as the University of Northern Colorado; the British Association for Romantic Studies; the Charles Lamb Society; and the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism.

For more information please visit johnthelwall.org.