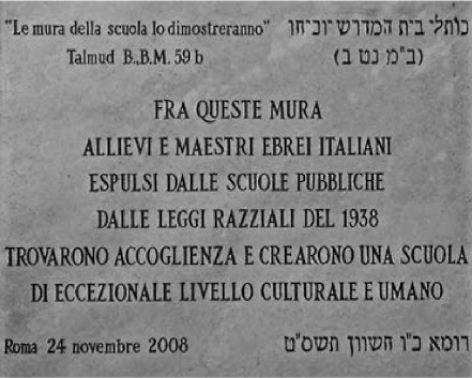

“Fra queste mura allievi e maestri ebrei italiani espulsi dalle scuole pubbliche dalle leggi razziali del 1938 trovarono accoglienza e crearono una scuola di eccezionale livello culturale e umano” (“Within these walls, Italian Jewish students and teachers, expelled from public schools by the racial laws of 1938, found a shelter and created a school of exceptional cultural and human level”), reads the plaque located at the entrance of the garden surrounding the Notre Dame Villa in Rome. The commemorative plaque was placed on November 24, 2008, 70 years after Italian racial laws during Fascism were promulgated.

During the meeting of the Gran Consiglio del Fascismo, which took place on the night between 6 and 7 October 1938 in Rome, racial laws were approved. The laws prohibited Jews from having any professional occupation, sexual relations or marriages with Italians, employing non-Jewish Italian domestics, serving in the military and attending all educational institutions. The Fascist government declared that Jewish children would not be allowed to attend public schools, so that Aryan children would not be contaminated. It was permitted, however, to establish some primary and secondary schools for Jewish children under the control of an Aryan commissioner, nominated by the Ministry of Public Education. In Rome, primary and secondary schools were instituted in less than two months.

A committee of parents found the building in Via Celimontana, which now hosts the ND Villa, and gathered the money to purchase the necessary equipment and obtained the appointment of Nicola Cimmino, an Italian and Aryan dean. On 23 November 1938 the Jewish school opened its gates to four different institutions: middle and high schools, “scuole magistrali inferiori e superiori”, and technical institutes. A total of 411 students, divided in 29 classes, attended the school during morning and evening shifts.

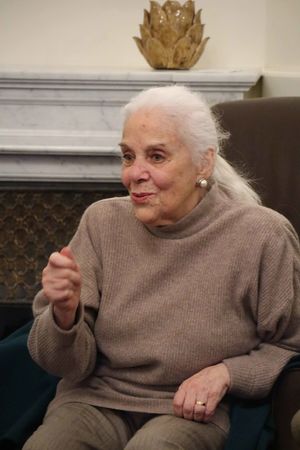

At the time the school opened, Giacometta Limentani was an 11-year-old child. On 23 November 1938, she moved to the Jewish school in Via Celimontana to attend her second year of middle school. Unlike other children her age, she already had experienced hardship. Her father was an anti-Fascist often taken from home, work, or the streets to be tortured and questioned. When Fascist soldiers returned him to his home, they would throw him on the floor as if he were garbage. Once, when she was eleven, four young Fascists came looking for her father, but he wasn’t there. Instead they found only Giacometta and her old, sick grandmother suffering from cataracts. They asked the little girl where her father was; when they weren’t happy with the answer they resorted to violence. Many years later, Giacometta described the extreme violence she experienced and how, as a result, she was not a typical child when she arrived at the school in Via Celimontana in 1938.

Giacometta was invited to visit the old Jewish School as it is today to meet and talk with the ND students studying abroad in Rome. Her testimony detailed what she experienced and also relayed her joyful years in the same building that protected her and many other students from the outside world.

In the living room of the Villa, students sat down, legs crossed, and listened to Giacometta and her friend, Paola Fano Modigliani, the daughter of a Jewish family who survived the Second World War, share their memories.

“This school represented for us a way of feeling safe and trusting our classmates. We knew here we could talk freely and trust each other always, because we were all coming from similar experiences. Inside the school there was the freedom of mind, freedom to speak, freedom to fall in love, freedom to make jokes and be normal children. But outside from here, if was very difficult to live, we had to smile, always smile, no matter what happened to us, we had to seem normal and serene from the outside,” Giacometta says. “In this school there was a different way of teaching. Professors would encourage discussion, would meet their students in a nearby Osteria to talk more deeply about every kind of topic. This enabled us to feel free to talk about what was happening outside, to feel safe, and to create a strong network of relationship among students and professors.”

“What happened after October 1943, after the Nazis came to arrest 1022 Jews and deport them to the network of labor and extermination camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau?” asked a student.

“My family and I were living in Cave, a town nearby Rome, where my dad created one of the first resistance groups in a friend’s villa that was a real arsenal. I was helping being a courier, stealing some food to eat, cutting the telephone cables of the Nazis, in this way I felt useful, I felt a person again.”

“And what happened when the war ended?” another student asked.

“The night the war ended, we were hiding in a Convent in Piazza di Spagna. My father screamed we were finally free and ran in the streets. I went on the terrace looking down, because they said that Nazis would have spread the false word the war was over only to gather more people in the streets and then capture them all. I was so afraid for my father that I thought that if I would have seen the Germans arrive I would have killed myself. I leaned over the balcony and I saw the last Nazi car leave and after a few minutes the first American Jeep arrive. It was the first time I saw such a strange car! I started crying and while I was weeping, an American soldier from the Jeep saw me and shouted to me, “Don’t cry, baby, don’t cry.” Soldiers were throwing so many candies at the people and everyone was so good-looking and clean.”

Giacometta left the ND Villa with a smile on her face, happy to have met such a lively and interested group of students in Rome. She was also grateful to have been given the chance of stepping again inside the building that set her free from a hostile outside world.

It is as if a circle now finally closes as the building goes back to its origins and turns, once again, into a school. It is restored into a place where students have the freedom to learn, explore their passions, raise questions, but most of all, a place where students will learn from the past in order to avoid repeating.

Originally published by at international.nd.edu on December 15, 2017.