A. P. Monta, Associate Director of the Nanovic Institute, was recently in western Ukraine to participate in the annual meeting of the Catholic Universities Partnership, hosted this year by Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. The following reflections for students are intended to stimulate proposals for research, internship, and service.

Location, Location, Location

Ukraine from orbit. Credit: Google.

Ukraine from orbit. Credit: Google.

Flying into Ukraine from the west, you will see that the countryside is mostly flat. The only mountains, and they are small, are located in the southwest (see map at right). The northern border of the country is hilly and forested. If you fly over these hills and follow this border to the east, you will pass over the city of Kiev and eventually turn north. Just around the bend lies Moscow. Fly south from Moscow, and you will see Ukraine divided roughly in half by the Dnieper River, which flows south and empties west of the Crimean peninsula into the Black Sea. Horses, carriages, and tanks have traveled easily across this country. The Black Sea has a large natural gas field. These are non-trivial facts that have had, and continue to have, regional geopolitical implications.

Polish/Ukrainian borderland, from the air.

Polish/Ukrainian borderland, from the air.

Topography is also important to understanding the history of Ukraine's relationship to Europe. There was, and is, no hard natural border between western Ukraine and what is now Poland. In the 16th and 17th centuries, this area ("Galicia") was part of a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the 18th century, churches in Galicia entered into communion with the Roman Catholic Church. (Because these churches continued to use the 'Byzantine' liturgy for Mass, they came to be called "Greek" Catholics.) There were then a few short-lived attempts to define and assert national independence, but in the late 18th century, the entire region was soon dismembered by its three neighboring empires: Russia, Prussia, and Austria-Hungary. Most of the country in the east came under control of the (Orthodox) Tsars; Galicia was controlled by the (Catholic) Habsburgs.

Founded by the Bavarian George Hoffmann in 1796, the George Hotel in Lviv, Ukraine, was rebuilt in the middle of the 19th century and remodeled along the lines of opera houses in Vienna and Torino. It had previously been the "De La Rus" hotel.

Founded by the Bavarian George Hoffmann in 1796, the George Hotel in Lviv, Ukraine, was rebuilt in the middle of the 19th century and remodeled along the lines of opera houses in Vienna and Torino. It had previously been the "De La Rus" hotel.

The Habsburg influence helps to explain why Ukraine today, particularly a western city like Lviv, feels so European. In architecture, references to multiple European traditions are everywhere. With its robust café culture and wealth of artistic and literary figures, Lviv became known in the 19th century as "Vienna of the East." The city served as a cultivated watering hole for artists and cultural bridge between central Europe and Moscow. Lviv was also multi-ethnic and multi-religious, being home at various points in its history to Jews, Armenians, Greek Catholics, and Orthodox Catholics. The changing names of the city itself (Leopolis, Lemberg, Lwòw, Lviv) reflect historical changes in the city's rulers and multi-ethnic, multi-religious, character. The history of this mixture has not always been peaceful.

The Long Arm of the Soviet Past

Soviet architecture in Lviv.

Soviet architecture in Lviv.

When the Habsburg Empire collapsed in 1918, chaos ensued. Lviv was briefly the capital of a short-lived West Ukrainian People's Republic, but the USSR imposed itself in 1922 as sovereign. Under Stalin, millions of Ukrainians were starved to death in an enforced famine ("Holodomor"). Then came the Nazis. Amid these rapidly changing threats, Ukrainian nationalists fought everyone: they formed and split political parties, made alliances both wise and unwise, and expelled Jews, Poles, and Armenians. Reimposing control after the war, the Soviets liquidated the Greek Catholic Church in 1946, forcing its adherents either to convert to (Russian-controlled) Orthodoxy or face exile. Many were sent to Soviet gulags. Most Ukrainian Greek Catholics went underground and were only granted limited amnesty in the mid-1950s. For another generation, Ukraine was dismembered and disintegrated.

Lviv central square, 2008. If these men were 70 years old at the time of the photo, they would have been born just before the Second World War and so lived their entire adult lives in the USSR.

Lviv central square, 2008. If these men were 70 years old at the time of the photo, they would have been born just before the Second World War and so lived their entire adult lives in the USSR.

The effects of Soviet rule were devastating. Some Ukrainians say that life in the Soviet Union was like living under an atheist mafia. Loyalty to official ideology was to replace any religious sense. One western Ukrainian said the whole experience was like being infantilized. Professional advancement required people to lie to themselves, inform on their neighbors, and participate in many forms of corruption. The kind of split personality people were forced to adopt in order to survive became habitual, so much so that some Ukrainians refer to homo Sovieticus as if it were a different species.

Flower seller and student in Lviv, central square, 2018.

Flower seller and student in Lviv, central square, 2018.

The USSR collapsed in 1991, but when you walk the streets of Lviv today, it is worth remembering that everyone you see who is over thirty years old lived in it. (Conversely, no one under the age of thirty did, which means that they are the first generation with no direct experience of the USSR.) The new era of independence did not mean that Soviet habits and mentalities simply disappeared. Adult men and women took their places in privatized professions and places of political and administrative power. Old habits and relationships continued to exist. At the same time, people who never believed in the system were able to reassert their religious and political identities and make them visible. It is this mixture of homo Sovieticus and homo post-Sovieticus that characterizes Ukraine today, and will do so for the next decade or more.

Economics, Power, and War

President Poroshenko ("Roshen") controls the leading manufacturers of confectionary products. This franchise location in Lviv was doing brisk business.

President Poroshenko ("Roshen") controls the leading manufacturers of confectionary products. This franchise location in Lviv was doing brisk business.

Perhaps the first thing to understand is that the current economy in Ukraine is inseparable from the regional, religious, and political legacies mentioned above. In the late 90s and early 00s, after the breakdown of the USSR's internal market, Ukraine's economy suffered a deep recession. Then came enormous wealth for a few. The emergence of administrative and economic oligarchy probably had something to do with the nature of the older generation: those who could capitalize (natch) on previous party and professional networks seized control of major economic sectors and worked with their peers in law and administration to establish a regulatory environment in which it became difficult to establish new businesses without paying multiple and exorbitant fees for various kinds of permissions. Consequently, the middle class economy in Ukraine stalled under the rules and mentality of a post-Soviet apparat. This kind of corruption produced slow growth, debt, and continues to perpetuate dishonesty, which among other things frustrates foreign trade. The oligarchs of course show little inclination to change it. There are exceptions, which are worth finding and exploring.

Combating brain drain? Windows of President Poroshenko's chocolate store in Lviv, depicting the central square in Lviv as full of young, creative people in love.

Combating brain drain? Windows of President Poroshenko's chocolate store in Lviv, depicting the central square in Lviv as full of young, creative people in love.

Unfortunately, Ukraine's labor market is considered weak by countries in the west. Educational institutions have been corrupted. For this reason, responsible parents of bright children often want their children to study in nearby Poland. So young people do, creating a brain drain. There is also talk that Poland has loosened immigration laws regarding Ukraine recently, such that students studying in Warsaw can apply to allow their parents to emigrate to Poland with them. The Polish zloty is also stronger than the hryvnia, creating a situation where Ukraine is treated more as a tourist destination than a place for investment. Such a position creates obvious tension between the two countries, which complicates the picture of what comprises Ukraine's regional threats.

Central Lviv, Jesuit Church. Memorial to a young Ukrainian soldier killed recently in the Donbass. The memorial changes about every ten days.

Central Lviv, Jesuit Church. Memorial to a young Ukrainian soldier killed recently in the Donbass. The memorial changes about every ten days.

Of course there is the most obvious threat: war. Remember the flat terrain all the way to Moscow? The Tsarist protectorate of the 19th century? The natural border of the Dnieper? These are dimension variables that have threatened Ukrainians yet again. In 2013, when Ukrainian President Yanukovych suspended preparations for developing an association agreement with the European Union, Ukrainians revolted against what they saw as re-absorption into authoritarian Russia. The Revolution of Dignity in 2014, started by students in Lviv and spreading to Kiev, was soon answered by Russia's annexation of Crimea. Irregular Russian troops have been operating in the Donbass region for years now, and Ukraine has since suffered more than 9,000 casualties in the low-profile, hybrid war.

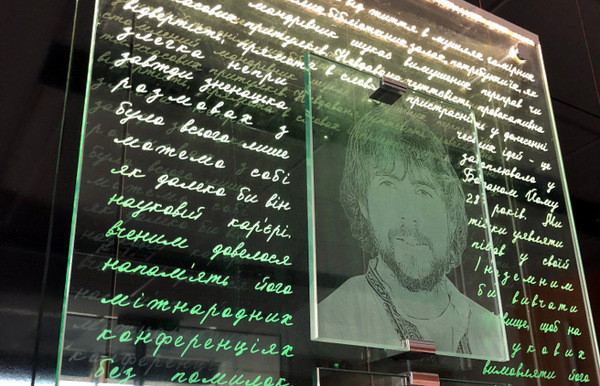

Memorial to Bohdan Solchanyk, a young history professor at Ukrainian Catholic University, killed on the Maidán by a government sniper. He was 28.

Memorial to Bohdan Solchanyk, a young history professor at Ukrainian Catholic University, killed on the Maidán by a government sniper. He was 28.

The war is visible today in Lviv as a steady-state conflict. The central Greek Catholic church downtown, next to city hall, creates a new memorial when each man is killed --- roughly every ten days. I spoke with a Russian-speaking Ukrainian embedded with a film crew at the front two weeks ago. He reported that the Ukrainian military has better training and equipment now and is doing better in the field: resistance is stiffening. If Russia were to push toward the Dnieper, "it would be a bloodbath." Russia seems content to let the conflict remain frozen and nip away at what it can.

Sources of Hope

It's easy to be optimistic in Lviv on a sunny day when old men are playing chess in the public square, young people are pushing around babies in carriages, and the city streets are bustling with shoppers, tourists, and admirers of all kinds. By all appearances, Lviv is the postcard ideal of a thriving European border city. But it is also quite clear that the sources of hope in Ukraine may not be economic, political, military, or policy-driven. The sources of hope are cultural. Meaning, what gives the western Ukrainians that we met the most hope has to do with education, values, and connectivity. The older generation (out of which comes its current leaders) was produced in a different culture. What is being cultivated now in Ukraine are some powerful alternatives worth exploring and, if possible, assisting.

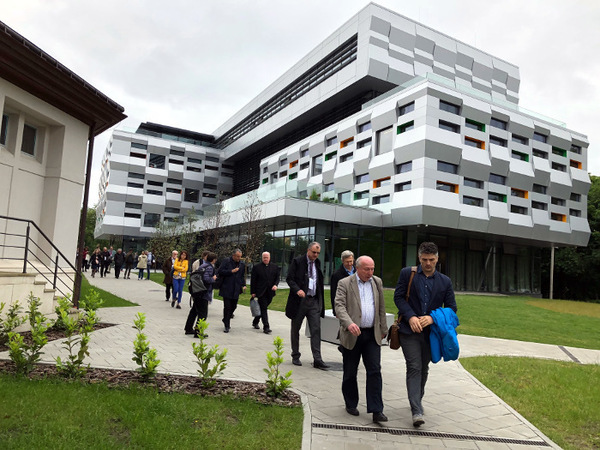

Ukrainian Catholic University, Lviv.

Ukrainian Catholic University, Lviv.

For example, the Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) in Lviv is an extraordinary achievement all by itself. A top-tier academic institution that operates transparently and with great managerial integrity, UCU represents the kind of operating system Ukraine most needs. But it does more than set a good example: it cultivates students to have a powerful sense of, and commitment to, the common good as a basis for civic life. Confident of this, UCU's students were central to recent political revolutions, the most spectacular of which was the Revolution of Dignity that took place on the Maidán in Kiev. Although there is no guarantee of success, this highly progressive combination of professional, spiritual, and civic formation is a source of great hope for the entire country.

Evangelical Christians and children's choir in Lviv.

Evangelical Christians and children's choir in Lviv.

A second source of hope may lie in the religious sense of Ukraine. The common heritage of Christianity, long suppressed and now resurgent, gives Ukraine a set of norms and an active spirit that can create an environment where common values can be grown and strengthened. It was spring when we visited Lviv, and, as it happened, Ascension Thursday: churches of all kinds were filled to capacity, young people were coming from all over the countryside to Lviv's churches to be married, and babies were evident (though a current demographic source reports Ukraine's fertility rate is well below replacement levels at 1.47). If Ukraine's young people can strengthen their Christian commitments, they may be able to strengthen other social norms by extension.

The young Deputy Mayor of Lviv, dreaming of the future.

The young Deputy Mayor of Lviv, dreaming of the future.

Last, the younger generation in Ukraine is, like the rest of the world, connected to the internet. Communication has revolutionized their social relations by expanding them permanently. The downside of complete connectivity is vulnerability to outside forces. The upside however is a new ability to forge sets of relationships and systems that are difficult if not impossible to suppress. If Ukraine's young people can build productive connections with their peers in both the East and West, their economic and political health could improve. The challenge in becoming more open however poses an internal challenge: the attenuation or dissolution of local ties that leads to brain drain and emigration. It remains to be seen whether new institutions in Ukraine like UCU can cultivate a strong enough sense of national affection to prevent the weakening of Ukraine's national identity. Such a weakening would leave it vulnerable again to disintegrative tendencies and other imperial projects.

All photos above are by the author unless otherwise noted.