Maria Rogacheva, a doctoral candidate in Notre Dame’s Department of History, is working to reveal the secrets of “invisible” communities that once housed the former Soviet Union’s scientific research facilities.

“Dozens of small- and medium-size towns were built from scratch across the country, kept secret from foreigners, and often not even placed on Soviet maps,” Rogacheva says. “Populated by scientists and their families, these white archipelagos were responsible for developing Soviet nuclear weapons and the heralded space program, among other things. They formed the core of the Soviet technological know-how, propelled the Soviet Union to superpower status, and threatened to make the Cold War hot.”

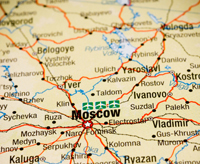

The opening of these small towns has opened up a wealth of opportunities for historical scholars such as Rogacheva, whose research centers on Chernogolovka, a formerly closed community just 40 miles from Moscow.

“My dissertation focuses on the history of a small Soviet town populated by scientists from 1956 to 1985,” she says. “I use this academic town as a lens through which I investigate the lives and work—as well as the shifting worldviews—of the late Soviet scientific intelligentsia.”

Lifting the Veil

Despite the importance of these communities, Rogacheva says, academics know almost nothing about the towns and their inhabitants. Until recently, scholars have had limited or no access to the relevant archives. Many of these locations didn’t officially “exist” until the mid 1990s—after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Though many scholars have begun studying the history of Soviet technology itself, the lives of the actual scientists and the development of their Weltanschauungen (worldview) has been largely ignored.

“Scholars have been encapsulated with the immediate causes of the fall of the Soviet regime (like perestroika), which has overshadowed developments within Soviet society in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s,” Rogacheva says. “Only in the last several years have historians begun to publish monographs on this exciting time. My dissertation seeks to contribute to this new wave of literature by examining Soviet scientists, the so-called ‘loyal’ majority of the Soviet intelligentsia.”

Rogacheva’s research examines four specific issues:

- what life was like for the residents of the isolated islands,

- how the scientists responded to the political and ideological crackdown of the 1960s and 1970s,

- why a majority of the intelligentsia remained loyal to the Soviet regime, and

- whether and to what extent there was a gradual disillusionment with the Soviet regime among post-1956 scientists—and how that might help explain the abrupt end of the Soviet experiment.

Entering New Territory

Rogacheva received a grant from the College of Arts and Letters’ Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts to help fund her research in Russia. There, she gained unprecedented access to a number of unique collections in Chernogolovka’s archives and conducted more than 25 interviews with former Soviet scientists about their lives in the town. The information she gained from these face-to-face encounters has proved invaluable to her research.

Rogacheva also was able to access several archival facilities in Moscow that contain party documents from Chernogolovka’s research institutes, including the Central Archive of Social and Political History, and the Russian State Archive of Contemporary History. In the latter, she examined recently declassified documents from the Departments of Science, Ideology, and Propaganda of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. She was also one of the first scholars to study the personal collections of Soviet scientists housed at the Russian Academy of Sciences, the head scientific organization of both the former Soviet Union and present-day Russia.

After the initial phase of her investigation, some of the directors of the archival centers even invited Rogacheva back to conduct more research.

“My research will be, in many respects, a pioneering study,” she says. “It will be one of the first works that combines oral interviews with original research in hitherto unexplored Russian archives. … I hope it will allow me to discern the particulars of people behind the allegedly monolithic facade of the Soviet technical intelligentsia.”

Paving the Way for Future Scholars

Rogacheva’s adviser Semion Lyandres, an associate professor in the Department of History and co-director of the Program in Russian and East European Studies, says Rogacheva is a very promising young scholar whose original contribution to the historiography of the Soviet Union is of “cardinal importance” for the field of Russian studies.

“There is no reliable work on the complex, multifaceted relations between the scientific intelligentsia and the Soviet state, even though the former was nothing other than the single most important—and one of the most privileged—professional groups in the USSR,” Lyandres says. “Writing the first serious intellectual history of this group is an ambitious and historiographically much-needed undertaking.”

Recently, Rogacheva traveled to Stockholm, Sweden, with Lyandres to present some of her findings at the VIII World Congress of International Council for Central and East European Studies and participated in a panel discussion about the transformation of identities in the late-era Soviet Union.

Once her dissertation is complete, she plans to expand the work into a book and donate her research to an archive such as the Hoover Institute at Stanford University, thus safeguarding this information and ensuring its availability to other scholars.

Learn More >

Originally published by at al.nd.edu on April 27, 2011.