"Cobblestoned streets, cozy common rooms, students with black robes, twisting spires, gothic architecture, a great hall—at first glance it seemed as though I had stepped into the pages of Harry Potter as I wound my way through Oxford. But alas, I was not at Hogwarts; no amounting of tapping on brick walls in London would take me through to Diagon Alley, and no matter how hard I pushed the trolley outside Platform 9 ¾ at King’s Cross Station it remained firmly stuck halfway through the wall." When Maria Fahs, a master's candidate in English, received a Graduate Break Travel and Research Grant to travel to the UK to explore and research the physical landscape of the Harry Potter series, she may not really have expected to enter Hogwarts, but she did expect to delve more deeply into the world of the series and the mind of the author. Along the way, she was surprised by some of her discoveries. Maria recently wrote to us about her experience:

When I embarked on my trip to Britain to explore how real places, events and other literary works influenced J. K. Rowling’s writing of and anxiety about Harry Potter, I expected to discover the ways in which the real shaped the fantastic within the series. What I did not expect to discover was that numerous parts of the British landscape have been influenced and changed by Rowling’s depiction of these real places and events. I theorized that part of Rowling’s desire to continually expand the world of Harry Potter in plays, movies, and online derived from her anxiety that the series will continue to grow beyond her control. I attributed this anxiety to her heavy borrowing of real places and events. What I did not realize was the extent to which the movies have influenced the world of Harry Potter, the ways in which the series has already very much grown beyond Rowling’s control, and how these real places within the series are not necessarily faithful depictions of actual places, but rather serve as inspirations for the locations within the series.

Early on in my research for my master’s thesis, The Author-Who-Lived: J. K. Rowling’s Refusal to Accept the Death of the Author in the Internet Age, I realized that most of the work that has been done on Harry Potter focuses on classical allusions, politics, history, social commentary, and literary references within the series. Although fans have long pilgrimaged and explored the real locations that served as inspiration for various parts of the series, little scholarly work has investigated what these real places might tell us about Rowling’s magical world. I sought to correct this deficit by exploring some of the most significant spatial and geographic inspirations within Harry Potter.

The gothic architecture of Oxford makes the city and the university feel like they are straight out of a storybook. The colleges themselves do not really resemble the Hogwarts houses, but the longstanding sense of tradition, college garb, formal dinners, and common rooms all lend themselves to comparisons with Hogwarts. Many locations at Oxford were used as filming locations for the series, including the Bodleian Library, the staircase and dining hall at Christ Church, the Duke Humfrey Library, and the New College Cloister. Both libraries were used to film scenes in the Hogwarts Library, and the Divinity School (on the lower ground floor of the Bodleian) was used for the Hospital Wing. The Cloister was the setting for Draco’s transformation into a ferret in the Goblet of Fire, and the staircase and dining hall at Christ’s Church were used for the Great Hall in the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Although many of these locations were chosen for filming the movie rather than appearing directly in the books, the dining hall at Christ Church bears such a striking resemblance to J. K. Rowling’s description of the Great Hall that I feel confident saying she likely had it in mind when she wrote the series. Aside from the physical resemblances that Oxford shares with Hogwarts, I was struck by the sense that Oxford considers itself the real-life Hogwarts. Every University bookstore carried Harry Potter clothing, just as they had apparel for each of the colleges. None of the students were in full academic dress when I visited (which is worn for all formal University ceremonies and exams), but their “uniforms,” called sub fusc, consist of dark skirts with tights or pants, black shoes, a white collared shirt, and a bow tie or tie, in addition to a mortar board. This is similar to the Hogwarts uniform, and many lower level schools in Britain also wear uniforms similar to those in the series. The students at Oxford are proud of their connection and similarities to Hogwarts and have embraced it as part of their collegiate identities.

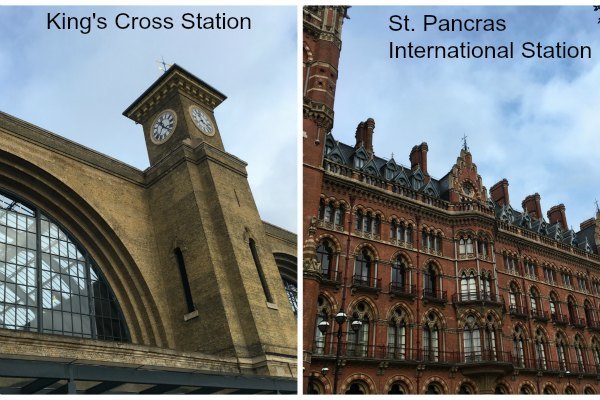

London also led to some interesting discoveries, particularly at King’s Cross Station. I was most intrigued by the importance of King’s Cross Station because it is both the beginning of J. K. Rowling’s personal story (it was where her parents met), and it is the beginning of Harry’s journey to Hogwarts and his entry into the wizarding world. For the Chamber of Secrets movie, the exterior of St. Pancras International Station was used, because it has a more impressive exterior and the two stations are adjacent. Inside King’s Cross Station, an externally accessible Platform 9 ¾ has been erected in the central concourse. Interestingly, the real location where Platform 9 ¾ should be does not bear any real resemblance to the description in the book. Platforms 9 and 10 are actually separate from the main train station and they are adjacent to each other. There is no wall between the two which could have served as an access point to Hogwarts. Film crews actually renumbered platforms 4 and 5 for the movie.

After doing some more research, I discovered that Rowling confessed that she was thinking of Euston, another train station, when writing the first book. Platforms 9 and 10 are also adjacent there, but these little misremembered details do not in any way diminish the importance of these real places; rather, they provided an important reminder that in the end real-life inspirations are a starting point, which serve to enrich and make a fictional world more vivid.

While exploring more of London, I stumbled unwittingly into Leadenhall Market which was used as the entrance to the Leaky Cauldron in the movie (the access point to Diagon Alley and the wizarding shopping district). I also visited Charing Cross Road, the actual location of the Leaky Cauldron in the books. Along the Southbank of the Thames I crossed the Millennium Bridge, which was destroyed in the Half-blood Prince movie. It was there I remembered that it is the Brockdale Bridge that is destroyed in the book. I also visited Cecil Court, known as the new Booksellers’ Row, which is full of valuable old books and signed first editions. This location is thought to be an inspiration for the Diagon Alley in the books because it links Charing Cross Road to St. Martin’s Lane.

Exploring these locations made me realize how much my perception and memories of the books have been influenced by the movie depictions. Although this was not necessarily something I expected to discover, it made me realize that perhaps Rowling’s desire to dictate how we remember Harry Potter and to personally expand his world is not so much a concern about her sources and influences, but a reaction against the way the series is already outside of her control. Oxford has adopted, or perhaps appropriated, Hogwarts; King’s Cross Station has memorialized Platform 9 ¾; and the Elephant House, where she used to write in Edinburgh, is a shrine to her creation. All of the places she has drawn on no longer simply serve as her inspirations; rather, they have in some sense become part of her creation because she has transformed them. This shows the profound impact of the series on the real landscape of Britain, and it offers a new way in which to explore the cultural legacy and transformative power of Harry Potter.

I am deeply indebted to the Nanovic Institute and its generous donors for this Graduate Break Travel and Research Grant. This trip helped me consider how place not only inspires fiction, but also changes as the result of literary creation. Thus far, my thesis has explored how online media like Twitter, Pottermore, authorial interviews, and news articles have changed our reading of the series. Thanks to this grant I have realized that I must examine the ways in which the movies have also shaped the series in the collective cultural memory, while pushing for further exploration of the geographic and locational inspirations behind the series. It is my hope that I will be able to spur a new avenue of inquiry within Harry Potter studies which will examine the reciprocal influence that real places have on magical spaces, and the way in which these real locations have been forever changed by Harry Potter and Rowling’s depiction of them within her seminal series.